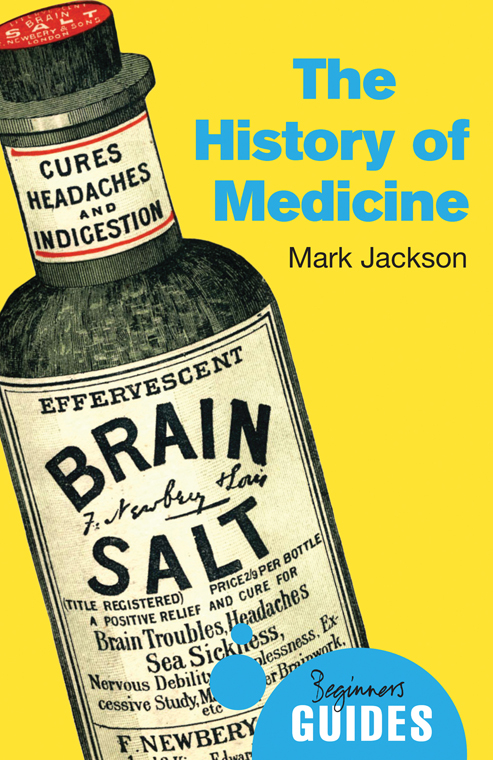

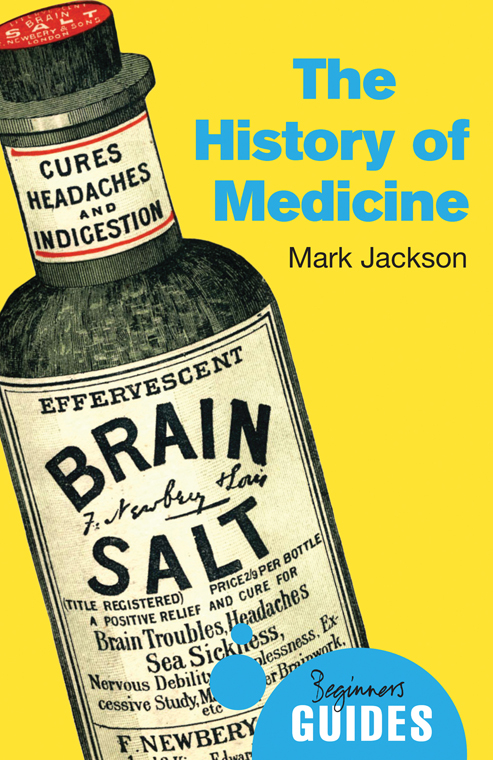

The History of Medicine

A Beginners Guide

As ever Mark Jackson offers us a humane and expansive view of the past to inform our vision of the future. As well as being a fantastic introduction to the history of medicine, this book is essential reading at a time when medical humanities scholars are for the first time working closely with clinicians and scientists to influence the direction of medical practice and therapy.

Jane Macnaughton Professor of Medical Humanities,

Durham University

Clearly written, up-to-date and informative, it will allow any reader (as well as any student of the history of medicine) to better understand those ethical, moral and cultural questions we face daily in our interaction with health care in new and surprising ways.

Sander Gilman Distinguished Professor of the Liberal

Arts and Sciences, Emory University

In one short book, Jackson has transformed the way we understand the theory and practice of medicine.

Joanna Bourke Professor of History, Birkbeck College,

University of London

This lively and accessible book forms an exciting new resource, as it sets about instructing students on the importance of studying medical history and the factors which have determined and impacted on health and medicine over time.

Linda Bryder Professor of History,

University of Aukland

A Oneworld Paperback

This ebook edition published by Oneworld Publications, 2014

Published in North America, Great Britain & Australia

by Oneworld Publications, 2014

Copyright Mark Jackson 2014

The right of Mark Jackson to be identified as the Author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-520-6

eISBN 978-1-78074-527-5

Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

For Ciara, Riordan and Conall

A heart is what a heart can do.

Sir James Mackenzie, 1910

Contents

Figure 1 | Chinese acupuncture chart |

Figure 2 | Vessel for cupping (a form of blood-letting) discovered in Pompeii, dating from the first century CE |

Figure 3 | Text and illustration on urinomancy or urine analysis |

Figure 4 | Mortuary crosses placed on the bodies of plague victims, c. 1348 |

Figure 5 | The dance of death or danse macabre , 1493 |

Figure 6 | Caring for the sick in the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, Siena |

Figure 7 | Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica , 1543 |

Figure 8 | Rembrandt van Rijn, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, 1632 |

Figure 9 | Illustration demonstrating the action of valves in the veins, William Harvey, De motu cordis , 1628 |

Figure 10 | Saint Elizabeth offers food and drink to a patient in a hospital in Marburg, Germany, 1598 |

Figure 11 | Etching of an obese, gouty man by James Gillray, 1799 |

Figure 12 | Gin Lane, an engraving by William Hogarth, 1751 |

Figure 13 | A caricature of a man-midwife, 1793 |

Figure 14 | Caricature of a cholera patient experimenting with remedies, Robert Cruikshank, 1832 |

Figure 15 | Joseph T. Clover demonstrating his chloroform inhaler on a patient, 1862 |

Figure 16 | Lithograph of Louis Pasteur, celebrating his work on rabies, 1880s |

Figure 17 | Advance dressing station in the field during the First World War |

Figure 18 | Advertisement for toothpaste, 1940s |

Figure 19 | X-ray showing a fractured wrist, 1918 |

Writing this book has provided me with an opportunity to indulge two complementary aspects of my constitution: a passion for science and medicine on the one hand, and a commitment to history and the humanities on the other. Many years ago, in an earlier and more troubled life, I qualified in, and for a brief period practised, medicine. Although the problems of pathology and the challenges of clinical medicine held, and continue to hold, an enduring appeal, I found it increasingly difficult to cope at the time with the psychological and physical demands of the clinic and became frustrated by the narrow conceptual horizons of modern medical education, research and practice. After completing a doctoral dissertation on the history of legal medicine, a new pathway opened up for me as I began to explore, from a historical perspective, the social, cultural and political determinants of both medical knowledge and personal experiences of health and illness. This choice of career was fortuitous. A life in academia has allowed me to reconcile contradictory facets of my intellectual interests, to manage the vagaries of my personality as well as fluctuations in mood and energy, to engage constructively with colleagues and students, and to share more equally the pleasures and demands of marriage and parenthood with Siobhn.

My transition from dispirited physician to aspiring historian of medicine has been facilitated by numerous friends and colleagues. In particular, I have been encouraged and stimulated by the work of Roberta Bivins, Bill Bynum, Mike Depledge, Paul Dieppe, Chris Gill, Rhodri Hayward, Ludmilla Jordanova, Staffan Mller-Wille, John Pickstone, Roy Porter, Ed Ramsden, Matt Smith, Ed Watkins, John Wilkins and Allan Young, and by the continued support of postgraduate students, post-doctoral fellows and administrative staff in the Centre for Medical History, especially Fred Cooper, Barbara Douglas, Claire Keyte, John Ford, Jana Funke, Ali Haggett, Sarah Hayes, Grace Leggett, Kayleigh Nias, Debbie Palmer, Lyndy Pooley, Pam Richardson and Leah Songhurst. I am grateful to Steve Smith, Nick Talbot, Nick Kaye and Andrew Thorpe at the University of Exeter for their willingness to endorse my research initiatives. More directly, the form and content of this book have been strongly informed by lectures and seminars delivered to undergraduate and postgraduate students at Manchester and Exeter, and by various opportunities to teach GCSE and A level students at Colyton Grammar School and other local schools and colleges. I am grateful to all those students for listening, arguing, and sometimes agreeing.

Of course, none of these research and teaching activities would be possible without the enlightened support of the Wellcome Trust, which has been instrumental in shaping not only the emergence of the history of medicine in recent decades but also the growth of medical humanities. The Trusts commitment to rendering historical research instrumental in the pursuit of better health has generated opportunities for greater, and more meaningful, exchange between science and the humanities and helped to sustain my dream of uniting disparate aspects of the practice of medicine. I am also grateful to Wellcome Images for providing, and allowing me to reproduce, the illustrations and to Caroline Morley and Miriam Ward for their assistance. I am greatly indebted to Fiona Slater of Oneworld, who first suggested that I write a book of this nature on this topic. Fionas vision and advice have been crucial both to the initial formulation and the eventual realization of the work. I would also like to thank Ann Grand for her meticulous copy-editing and David Inglesfield and Linda Smith for their careful proof-reading.

Next page