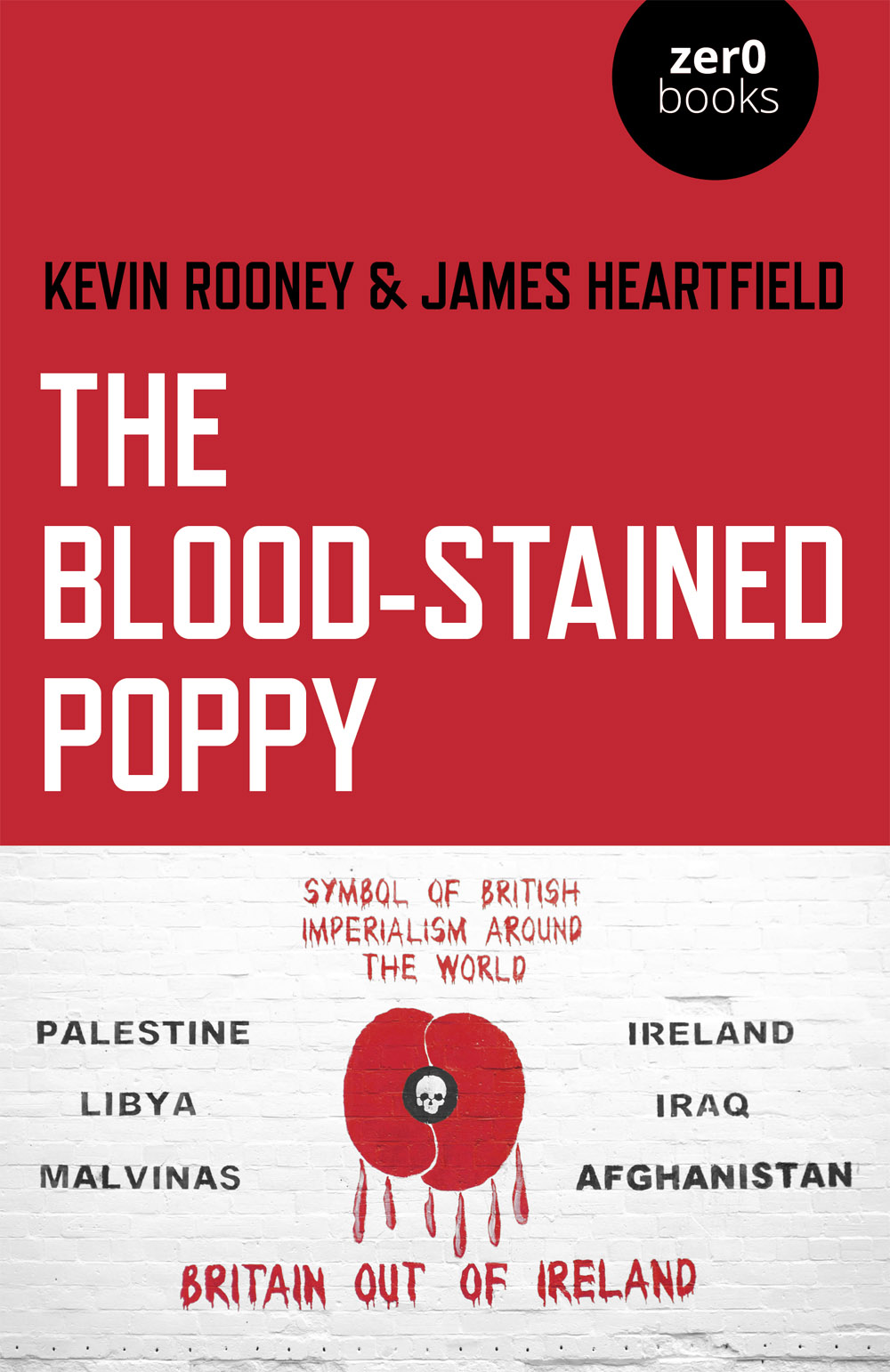

The Blood-Stained Poppy

JOHN HUNT PUBLISHING

First published by Zero Books, 2019

Zero Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., No. 3 East St., Alresford,

Hampshire SO24 9EE, UK

www.johnhuntpublishing.com

www.zero-books.net

For distributor details and how to order please visit the Ordering section on our website.

Text copyright: Kevin Rooney & James Heartfield 2018

ISBN: 978 1 78904 077 7

978 1 78904 078 4 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018945648

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers.

The rights of Kevin Rooney & James Heartfield as authors have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design: Stuart Davies

UK: Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

US: Printed and bound by Thomson-Shore, 7300 West Joy Road, Dexter, MI 48130

We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution.

Contents

Guide

Also by the Authors

Whos Afraid of the Easter Rising?, Zero Books, 2015

At half-time during a football game at Celtic Park in 2010, a group of Celtic supporters unfurled a banner which read:

Your deeds they would shame all the devils in hell. Ireland, Iraq, Afghanistan. No blood-stained poppy on our hoops.

It was a protest against the clubs decision to mark Remembrance Day by getting the players to wear red poppies on their famous green and white jerseys and observe a minutes silence before the game. Anyone who knows the history and traditions of Celtic Football Club would not have been too surprised to see a group of fans unfurling an anti-war banner. A significant section of the support would self-identify as left-wing and anti-imperialist. A significant section would be sympathetic to Irish republicanism and other similar causes like expressing solidarity with the Palestinians. None of this is new. These fans have a long record of voicing opposition to what they see as British militarism. Expecting every Celtic supporter to accept without protest the implanting of the Earl Haig poppy onto the club jersey was never going to happen.

It was a remarkable demonisation of people for staging a peaceful protest. John Reid, club chairman and former Labour Home Secretary, pledged to hunt down this hate-mob and ban them from Celtic Park for life. One MP argued that the club needed to go further to lance this boil. Celtic Shame, yobs and louts were typical newspaper headlines reporting the protest. There were calls for the police to arrest the perpetrators. The police duly promised to track these people down. In the years since, Celtic fans have been threatened with arrest for declining to observe the Remembrance Day minutes silence before matches.

If refusing to accept the imposition of a minutes silence to honour soldiers who fought in wars you disagree with can get you arrested, then it is time to speak out. Britain is becoming a very intolerant society where basic civil liberties can no longer be taken for granted. In recent years a culture of conformism surrounding the politics of military remembrance has emerged where to question anything about it is to be judged deviant and beyond the pale.

Celtic fans protest against the poppy

Not every example of poppymania is so sharply contested. In 2014 artist Paul Cummins planted 888,246 ceramic poppies, one for each of the British and colonial war dead, in the moat of the Tower of London. It was an impressive field of red that moved many. The art worked because of the sheer number of poppies, and our knowing that each one was a life lost. But that is to make us think about the great sorrow of so many lives lost, without thinking about why. In official commemorations sadness for the soldiers killed is turned into a worship of the military institutions that sacrificed them. War memorials then and now take an emotional charge from the war dead. But they also turn the misery of war into a sanctification of the armies that made those wars.

In years gone by anti-war campaigners challenged the red poppy with a pacifist white poppy. If you really cared about the dead, the white poppy wearers said, you would fight against war. The Haig Fund (now the Royal British Legions Poppy Appeal) poppy sellers reacted angrily to the Peace Pledge Unions white poppy when it first appeared.

Nowadays there are other variations on the poppy theme. But their point is not to challenge the militarism implicit in the poppy appeal. Rather they are hoping to be recognised for the part they played in the war. There are black poppy badges to honour the West Indian and African regiments that fought in the Great War. The loyalists of Northern Ireland have badges that combine the poppy with the red hand of Ulster. Irelands Taoiseach has popularised the Shamrock Poppy, for the Irish who served in the British Army. There was even a purple poppy to recognise the animals that were killed in the war. Me too these badges say: I want to be included in the war dead. But we say that it is better that there should not be any more war dead.

Each year, the expectation to conform to poppymania grows. The sentimentalisation of areas of everyday life previously untouched by the politics of remembrance grows every year. Those who refuse to join in honouring British military dead are met with reprimands and restrictions. By all means let those who wish to honour the British military dead do so but let us defend the right of others to refuse. It is not only a problem of intolerance towards those who conscientiously object to the red poppy that needs to be challenged but also the unquestioning reverence with which everyone is now expected to treat the politics of the remembrance season.

In a climate where it has become more increasingly difficult to dispute the politics of official remembrance, there is a danger of historical amnesia setting in; it seems few really do remember why so many people died in Britains wars. We contend they rarely died for freedom. For the most part, they lost their lives in the service of British colonialism, Empire and the pursuit of reactionary ends. From Kenya to Malaysia, Cyprus to Iraq, the history of British militarism is shameful. That is why, once upon a time, there were many principled anti-imperialists in Britain and Ireland who stood up not only against war but also the red poppy and what it represented. Today unfortunately they are much fewer in number. Opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn once chose not to wear the poppy. For that he was attacked in the Press. After a heap of political and media pressure he now stands with the political and military elite at the Cenotaph in November with his head bowed. Who now will challenge the political and military elite who stand at Whitehall on 11 November?

Who will challenge the legitimacy of these decision makers responsible for unnecessary wars which sent people out to kill and be killed? This book intends to take up that baton. We stand full square in the anti-war camp and contend that to be anti-war means challenging the politics of official remembrance. It also requires a critique of the political and military leaders who stood at the Cenotaph in the past 100 years because they are largely culpable for the conflicts Britain has been involved in since the First World War. And did it help Jeremy Corbyn to go to the Cenotaph? No. He was criticised for not bowing deep enough.

Next page