Herbert Hall Turner - Astronomical Discovery

Here you can read online Herbert Hall Turner - Astronomical Discovery full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Astronomical Discovery

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Astronomical Discovery: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Astronomical Discovery" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Astronomical Discovery — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Astronomical Discovery" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE VARIATION OF LATITUDE 177

INDEX 221

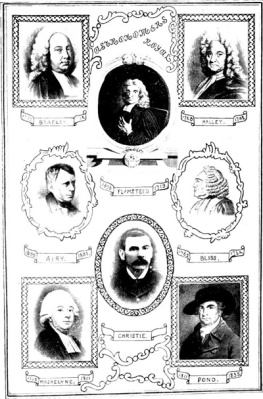

LIST OF PLATES

PLATE

I. PORTRAIT OF J. C. ADAMS To face page 22

II. PORTRAIT OF A. GRAHAM " " 22

III. PORTRAIT OF U. J. LE VERRIER " " 60

IV. PORTRAIT OF J. G. GALLE " " 60

V. CORNER OF THE BERLIN MAP BY THE USE OF WHICH GALLE FOUND NEPTUNE " " 82

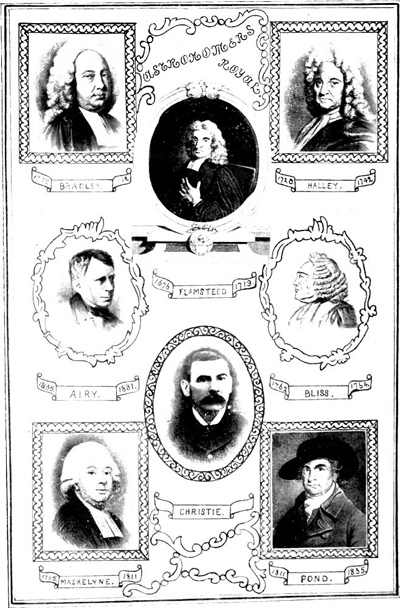

VI. ASTRONOMERS ROYAL Frontispiece

VII. GREAT COMET OF NOV. 7, 1882 To face page 122

VIII. THE OXFORD NEW STAR " " 142

IX. NEBULOSITY ROUND NOVA PERSEI " " 146

X. SUN-SPOTS AT GREENWICH, FEB. 18 AND 19, 1894 " " 158

XI. SUN-SPOTS AT GREENWICH, FEB. 20 AND 21, 1894 " " 162

XII. NUMBER OF SUN-SPOTS COMPARED WITH DAILY RANGE OF MAGNETIC DECLINATION AND DAILY RANGE OF MAGNETIC HORIZONTAL FORCE " " 164

XIII. GREENWICH MAGNETIC CURVES, 1859-60 " " 166

XIV. GREENWICH MAGNETIC CURVES, 1841-1860 " " 166

XV. SUN-SPOTS AND TURNS OF VANE " " 170

ERRATA

Page 133, line 27, for "200 stars" read "200 stars per hour."

" 145, See note on page 220.

" 146, bottom of page. This nebulosity was first discovered by Dr. Max Wolf of Heidelberg. See Astr. Nachr. 3736.

" 181, line 17, for "observation" read "aberration."

ASTRONOMICAL DISCOVERY

URANUS AND EROS

[Sidenote: Popular view of discovery.]

Discovery is expected from an astronomer. The lay mind scarcely thinks of a naturalist nowadays discovering new animals, or of a chemist as finding new elements save on rare occasions; but it does think of the astronomer as making discoveries. The popular imagination pictures him spending the whole night in watching the skies from a high tower through a long telescope, occasionally rewarded by the finding of something new, without much mental effort. I propose to compare with this romantic picture some of the actual facts, some of the ways in which discoveries are really made; and if we find that the image and the reality differ, I hope that the romance will nevertheless not be thereby destroyed, but may adapt itself to conditions more closely resembling the facts.

[Sidenote: Keats' lines.]

The popular conception finds expression in the lines of Keats:-

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken.

Keats was born in 1795, published his first volume of poems in 1817, and died in 1821. At the time when he wrote the discovery of planets was comparatively novel in human experience. Uranus had been found by William Herschel in 1781, and in the years 1800 to 1807 followed the first four minor planets, a number destined to remain without additions for nearly forty years. It would be absurd to read any exact allusion into the words quoted, when we remember the whole circumstances under which they were written; but perhaps I may be forgiven if I compare them especially with the actual discovery of the planet Uranus, for the reason that this was by far the largest of the five--far larger than any other planet known except Jupiter and Saturn, while the others were far smaller--and that Keats is using throughout the poem metaphors drawn from the first glimpses of "vast expanses" of land or water. Perhaps I may reproduce the whole sonnet. His friend C. C. Clarke had put before him Chapman's "paraphrase" of Homer, and they sat up till daylight to read it, "Keats shouting with delight as some passage of especial energy struck his imagination. At ten o'clock the next morning Mr. Clarke found the sonnet on his breakfast-table."

SONNET XI

On first looking into Chapman's "Homer"

Much have I travell'd in the realms of gold, And many goodly states and kingdoms seen; Round many western islands have I been Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold. Oft of one wide expanse had I been told That deep-brow'd Homer ruled as his demesne; Yet did I never breathe its pure serene Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold: Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken; Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes He star'd at the Pacific--and all his men Look'd at each other with a wild surmise-- Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

[Sidenote: Comparison with discovery of Uranus.]

Let us then, as our first example of the way in which astronomical discoveries are made, turn to the discovery of the planet Uranus, and see how it corresponds with the popular conception as voiced by Keats. In one respect his words are true to the life or the letter. If ever there was a "watcher of the skies," William Herschel was entitled to the name. It was his custom to watch them the whole night through, from the earliest possible moment to daybreak; and the fruits of his labours were many and various almost beyond belief. But did the planet "swim into his ken"? Let us turn to the original announcement of his discovery as given in the Philosophical Transactions for 1781.

PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, 1781

XXXII.--ACCOUNT OF A COMET

BY MR. HERSCHEL, F.R.S.

(Communicated by Dr. Watson, jun., of Bath, F.R.S.)

Read April 26, 1781

[Sidenote: Original announcement.]

"On Tuesday the 13th of March, between ten and eleven in the evening, while I was examining the small stars in the neighbourhood of H Geminorum, I perceived one that appeared visibly larger than the rest; being struck with its uncommon magnitude, I compared it to H Geminorum and the small star in the quartile between Auriga and Gemini, and finding it to be so much larger than either of them, suspected it to be a comet.

"I was then engaged in a series of observations on the parallax of the fixed stars, which I hope soon to have the honour of laying before the Royal Society; and those observations requiring very high powers, I had ready at hand the several magnifiers of 227, 460, 932, 1536, 2010, &c., all which I have successfully used upon that occasion. The power I had on when I first saw the comet was 227. From experience I knew that the diameters of the fixed stars are not proportionally magnified with higher powers as the planets are; therefore I now put on the powers of 460 and 932, and found the diameter of the comet increased in proportion to the power, as it ought to be, on a supposition of its not being a fixed star, while the diameters of the stars to which I compared it were not increased in the same ratio. Moreover, the comet being magnified much beyond what its light would admit of, appeared hazy and ill-defined with these great powers, while the stars preserved that lustre and distinctness which from many thousand observations I knew they would retain. The sequel has shown that my surmises were well founded, this proving to be the Comet we have lately observed.

"I have reduced all my observations upon this comet to the following tables. The first contains the measures of the gradual increase of the comet's diameter. The micrometers I used, when every circumstance is favourable, will measure extremely small angles, such as do not exceed a few seconds, true to 6, 8, or 10 thirds at most; and in the worst situations true to 20 or 30 thirds; I have therefore given the measures of the comet's diameter in seconds and thirds. And the parts of my micrometer being thus reduced, I have also given all the rest of the measures in the same manner; though in large distances, such as one, two, or three minutes, so great an exactness, for several reasons, is not pretended to."

[Sidenote: Called first a comet.]

[Sidenote: Other observers would not have found it at all.]

At first sight this seems to be the wrong reference, for it speaks of a new comet, not a new planet. But it is indeed of Uranus that Herschel is speaking; and so little did he realise the full magnitude of his discovery at once, that he announced it as that of a comet; and a comet the object was called for some months. Attempts were made to calculate its orbit as a comet, and broke down; and it was only after much work of this kind had been done that the real nature of the object began to be suspected. But far more striking than this misconception is the display of skill necessary to detect any peculiarity in the object at all. Among a number of stars one seemed somewhat exceptional in size, but the difference was only just sufficient to awaken suspicion in a keen-eyed Herschel. Would any other observer have noticed the difference at all? Certainly several good observers had looked at the object before, and looked at it with the care necessary to record its position, without noting any peculiarity. Their observations were recovered subsequently and used to fix the orbit of the new planet more accurately. I shall remind you in the next chapter that Uranus had been observed in this way no less than seventeen times by first-rate observers without exciting their attention to anything remarkable. The first occasion was in 1690, nearly a century before Herschel's grand discovery, and these chance observations, which lay so long unnoticed as in some way erroneous, subsequently proved to be of the utmost value in fixing the orbit of the new planet. But there is even more striking testimony than this to the exceptional nature of Herschel's achievement. It is a common experience in astronomy that an observer may fail to notice in a general scrutiny some phenomenon which he can see perfectly well when his attention is directed to it: when a man has made a discovery and others are told what to look for, they often see it so easily that they are filled with amazement and chagrin that they never saw it before. Not so in the case of Uranus. At least two great astronomers, Lalande and Messier, have left on record their astonishment that Herschel could differentiate it from an ordinary star at all; for even when instructed where to look and what to look for, they had the greatest difficulty in finding it. I give a translation of Messier's words, which Herschel records in the paper already quoted announcing the discovery:-

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Astronomical Discovery»

Look at similar books to Astronomical Discovery. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Astronomical Discovery and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.