Contents

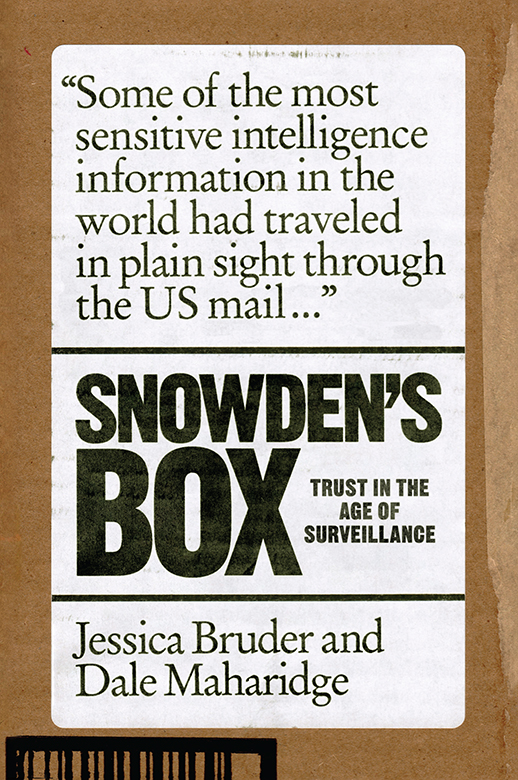

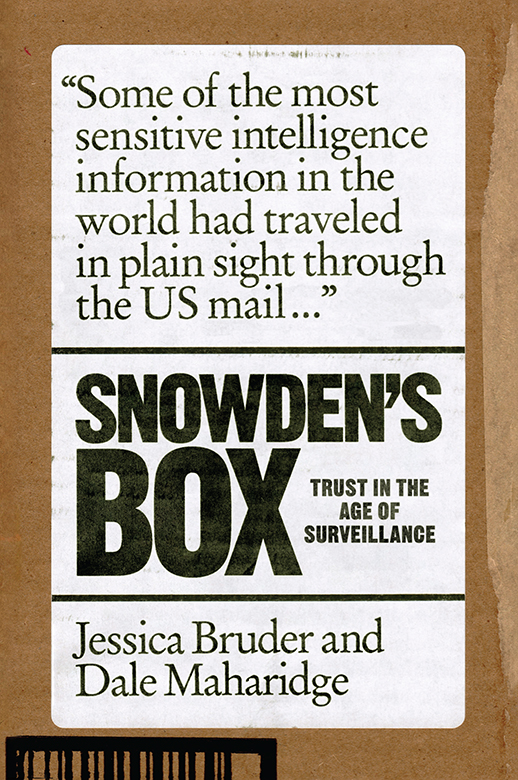

SNOWDENS BOX

SNOWDENS BOX

Trust in the Age of Surveillance

By Jessica Bruder and Dale Maharidge

First published by Verso 2020

Jessica Bruder, Dale Maharidge 2020

Parts of this book appeared originally under the same title in Harpers Magazine, May 2017

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-343-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-346-5 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-345-8 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bruder, Jessica, author. | Maharidge, Dale, author.

Title: Snowdens box : trust in the age of surveillance / By Jessica Bruder and Dale Maharidge.

Description: First edition hardback. | London ; New York : Verso, 2020. | Parts of this book appeared originally under the same title in Harpers Magazine, May 17, 2017T.p verso. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019038432 | ISBN 9781788733434 (hardback) | ISBN 9781788733465 (ebk) | ISBN 9781788733458 (ebk)

Subjects: LCSH: Snowden, Edward J., 1983 | Electronic surveillanceUnited States. | Confidential communicationsUnited States. | JournalismPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory21st century.

Classification: LCC JF1525.W45 B78 2020 | DDC 327.12730092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019038432

Typeset in Adobe Garamond by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

For Max

Once you have the data local to you, copy it to more media in off-site locations so it is unlikely to be confiscated. Literally bury a backup copy in the woods, that sort of thing.

Edward L. Snowden, in an encrypted

email to Laura Poitras, February 4, 2013

Ive seen the nations rise and fall.

Ive heard their stories, heard them all.

But loves the only engine of survival.

Leonard Cohen, The Future

Contents

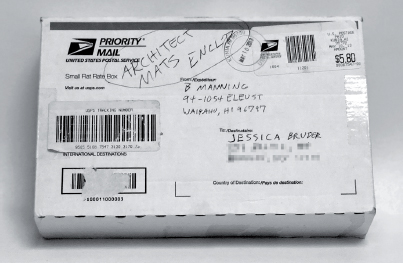

In the spring of 2013, an unauthorized trove of NSA files traveled nearly 5,000 miles in the care of the US Postal Service.

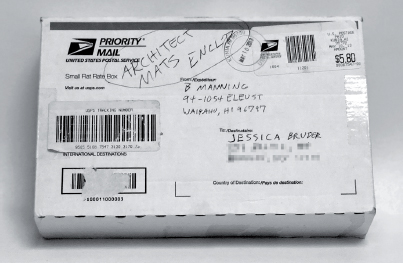

Postmarked May 10 at a former pineapple plantation village on the island of Oahu, the box of secrets soared east over the Pacific Ocean in a small flat-rate box, bearing a stamp for $5.80. It traversed the breadth of America before landing, unceremoniously, on the fourth floor of a nondescript walk-up apartment building in Brooklyn.

The sender had shipped the box via Priority Mail. Hed addressed it to a person hed never met at a home hed never seen. The recipient, in turn, knew nothing about him or the contents of the box. Her job was simple: carry it to a third person, who would ferry the package to its final destination.

At the time, to the best of the senders knowledge, no one was paying attention.

By the first week of June, the whole world was watching. Secrets began streaming out of the box, onto the front pages of newspapers. They included evidence that the US government had created a massive surveillance apparatus and used it to spy on its own people. Intelligence officials blasted the unidentified source of the leaks and, warning of dire consequences, prepared to launch a criminal probe.

But before anyone could unmask him, the leaker revealed himself. The cover of the Guardian bore a giant yellow headline: The Whistleblower. Below it appeared a photo of Edward Joseph Snowden. The twenty-nine-year-old had a patchy goatee and an earnest expression. He wore rectangular, semi-rimless Burberry eyeglasses these would soon become iconic with the left nose pad inexplicably missing. He identified himself as an NSA infrastructure analyst working for the defense contractor Booz Allen Hamilton.

The materials hed taken, Snowden told reporters, revealed an existential threat to democracy.

I dont want to live in a world where theres no privacy and therefore no room for intellectual exploration and creativity, he added.

In the years that followed, Snowdens story would be told and retold, a ballad for our times. The saga unfolded in films, including Laura Poitrass Oscar-winning documentary Citizenfour and Oliver Stones biopic Snowden, and in such books as No Place to Hide by Glenn Greenwald, Luke Hardings The Snowden Files, and, most recently, Snowdens own memoir, Permanent Record.

Missing from those chronicles so far has been a small but crucial episode the journey of a plain cardboard box that passed through strangers hands, setting the rest of the story in motion. In its absence grew a question: if the American governments surveillance was so mighty, so all-seeing, how did a motherlode of classified information get spirited away by mail, right under the watchers noses?

The answer may be simpler than you think.

The story of Snowdens box is deeply human, somewhat messy, and more than a little weird. Its about a brief moment when strangers worked together to build an underground railroad for secrets a high-stakes endeavor that relied, more than anything, on bonds of trust.

Thats no small thing. We live in an era of suspicion, marked by an eroding faith in government, the media, and even each other. Social scientists have studied the decline of public confidence, quizzing Americans on the same set of topics over and over for nearly half a century as part of a long-term project called the General Social Survey. It includes this question:

Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you cant be too careful in dealing with people?

Researchers ran the first round of the survey in 1972. At the time, nearly half of the people who responded said they trusted others. By the latest round in 2018 two years after Donald Trump was elected president the figure had dropped to less than a third.

Thats scary news. Trust is the basis of all cooperative action in a free society. Its the feeling of fellowship that allows people to take risks and grow. Its also the underpinning of democracy. And its fragile, easy to undermine. Massive domestic spying systems like the one Snowden revealed are corrosive to the kind of deep human connections that nourish trust and collaboration.

Consider East Germany, the most notorious surveillance state in modern history. Its secret police force the Ministerium fr Staatssicherheit, better known as the Stasi was created in 1950. By the time it disbanded four decades later, the Stasi had grown to include some 86,000 full-time employees. If you add part-time and unofficial agents, the total number of people spying for the secret police had risen to more than half a million.

The population was saturated with snoops. Some estimates set the ratio at one informer to every six and a half citizens. Most major institutions from universities to churches and political parties were infiltrated. Neighbors snitched on neighbors, and mistrust was rampant. Even a member of the nations Olympic bobsledding team, Harald Czudaj, confessed to spying on his fellow athletes. Years later, he recounted through tears that police had caught him driving drunk and blackmailed him into becoming an informer.