Table of Contents

FROM THE PAGES OFMY BONDAGE AND MY FREEDOM

Genealogical trees do not flourish among slaves. (page 40)

My poor mother, like many other slave-women, had many children, but NO FAMILY! (pages 49-50)

That plantation is a little nation of its own, having its own language, its own rules, regulations and customs. The laws and institutions of the state, apparently touch it nowhere. The troubles arising here, are not settled by the civil power of the state. The overseer is generally accuser, judge, jury, advocate and executioner. The criminal is always dumb. The overseer attends to all sides of a case. (page 60)

Under the whole heavens there is no relation more unfavorable to the development of honorable character, than that sustained by the slaveholder to the slave. Reason is imprisoned here, and passions run wild. (page 72)

The slave is a subject, subjected by others; the slaveholder is a subject, but he is the author of his own subjection. There is more truth in the saying, that slavery is a greater evil to the master than to the slave, than many, who utter it, suppose. (page 89)

From my earliest recollections of serious matters, I date the entertainment of something like an ineffaceable conviction, that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace; and this conviction, like a word of living faith, strengthened me through the darkest trials of my lot. (page 113)

Nature has done almost nothing to prepare men and women to be either slaves or slaveholders. (page 122)

How vividly, at that moment, did the brutalizing power of slavery flash before me! Personality swallowed up in the sordid idea of property! Manhood lost in chattelhood! (page 138)

Make a man a slave, and you rob him of moral responsibility. Freedom of choice is the essence of all accountability (page 149)

The over work, and the brutal chastisements of which I was the victim, combined with that ever-gnawing and soul-devouring thoughtI am a slaveaslave for lifeaslave with no rational ground to hope for freedomrendered me a living embodiment of mental and physical wretchedness. (page 169)

I had reached the point, at which I was not afraid to die. This spirit made me a freeman in fact, while I remained a slave in form. (page 187)

I longed to have a futurea future with hope in it. To be shut up entirely to the past and present, is abhorrent to the human mind; it is to the soulwhose life and happiness is unceasing progress-what the prison is to the body; a blight and mildew, a hell of horrors. The dawning of this, another year, awakened me from my temporary slumber, and roused into life my latent, but long cherished aspirations for freedom. (page 206)

To make a contented slave, you must make a thoughtless one. (page 238)

Toward fugitives, Americans are not honest. (page 256)

A slave, brought up in the very depths of ignorance, assuming to instruct the highly civilized people of the north in the principles of liberty, justice, and humanity! The thing looked absurd. Nevertheless, I persevered. (page 292)

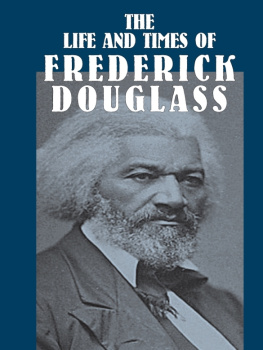

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born a slave in Tuckahoe, Maryland, in February 1818. He became a leading abolitionist and womens rights advocate and one of the most influential public speakers and writers of the nineteenth century.

Fredericks mother, Harriet Bailey, was a slave; his father was rumored to be Aaron Anthony, manager for the large Lloyd plantation in St. Michaels, Maryland, and his mothers master. Frederick lived away from the plantation with his grandparents, Isaac and Betsey Bailey, until he was six years old, when he was sent to work for Anthony

When Frederick was eight, he was sent to Baltimore as a houseboy for Hugh Auld, a shipbuilder related to the Anthony family through marriage. Aulds wife, Sophia, began teaching Frederick to read, but Auld, who believed that a literate slave was a dangerous slave, stopped the lessons. From that point on, Frederick viewed education and knowledge as a path to freedom. He continued teaching himself to read; in 1831 he bought a copy of The Columbian Orator, an anthology of great speeches, which he studied closely.

In 1833 Frederick was sent from Aulds relatively peaceful home back to St. Michaels to work in the fields. He was soon hired out to Edward Covey, a notorious slave-breaker who beat him brutally in an effort to crush his will. However, on an August afternoon in 1834, Frederick stood up to Covey and beat him in a fight. This was a turning point, Douglass has said, in his life as a slave; the experience reawakened his desire and drive for liberty.

After a failed escape attempt, Frederick was sent back to Baltimore, where he again worked for Hugh Auld, this time as a ship caulker. In Baltimore he met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman.

In 1838 Frederick Bailey escaped from slavery by using the papers of a free seaman. He traveled north to New York City, where Anna Murray soon joined him. Later that year, Frederick and Anna married and moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts. Though settled in the North, Frederick was a fugitive, technically still Aulds property. To protect himself, he became Frederick Douglass, a name inspired by a character in Sir Walter Scotts poem Lady of the Lake.

Douglass began speaking against slavery at abolitionist meetings and soon gained a reputation as a brilliant orator. In 1841 he began working full-time as an abolitionist lecturer, touring with one of the leading activists of the day, William Lloyd Garrison.

Douglass published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, in 1845. The book became an immediate sensation and was widely read both in America and abroad. Its publication, however, jeopardized his freedom by exposing his true identity. To avoid capture as a fugitive slave, Douglass spent the next several years touring and speaking in England and Ireland. In 1846 two friends purchased his freedom. Douglass returned to America, an internationally renowned abolitionist and orator.

Douglass addressed the first Womens Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. This began his long association with the womens rights movement, including friendships with such well-known suffragists as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

During the mid-1840s Douglass began to break ideologically from William Lloyd Garrison. Whereas Garrisons abolitionist sentiments were based in moral exhortation, Douglass was coming to believe that change would occur through political means. He became increasingly involved in antislavery politics with the Liberty and Free-Soil Parties. In 1847 Douglass established and edited the politically oriented, antislavery newspaper the North Star.

During the Civil War, President Lincoln called upon Douglass to advise him on emancipation issues. In addition, Douglass worked hard to secure the right of blacks to enlist; when the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteers was established as the first black regiment, he traveled throughout the North recruiting volunteers.

Douglasss governmental involvement extended far beyond Lincolns tenure. He was consulted by the next five presidents and served as secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (1871), marshal of the District of Columbia (18771881), recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia (18811886), and minister to Haiti (18891891). A year before his death Douglass delivered an important speech, The Lessons of the Hour, a denunciation of lynchings in the United States.

Next page