ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There is one basic truth in the South Asian immigrant experience: Do as your parents tell you. This notion was put to the test during my junior year of college, when I informed my father and mother that I wanted to study sociology. My mother seemed agnostic, but such decisions were made by my father, who said he preferred that I stay on the path toward a degree in bioengineering. I was not interested in science, and after several conversations we reached a compromise: I would study theoretical mathematics.

I knew that my father supported me, and I even understood his rationale. We were immigrants with no connections, no wealth, and all we had lay between our ears; a math degree would at least guarantee me a job.

A year later, when I told my father I wanted to apply to graduate programs in sociology, he continued to support me, giving advice that I now share with my own students. His counsel often took the form of parables and was laden with examples of people he had seen succeed (and fail). What he told me might take a full evening to relay, over wine and my mothers cooking, but the essence was always clear: write every day, visit your professors with well-formed questions, and always read everything that is recommended, not just what the professor requires.

He also taught me to shut up and listen to my advisers. In contemporary American institutions of higher learning, most people would find this instruction quaint; during a time in which the student has become the customer, this sort of thinking is considered anathema. But my father was no fan of the American educational system, so he insisted that I spend my time listening. I owe my father more than he will ever know. In life, love, and work, his wisdom would prove exceedingly valuable.

Within a few weeks of my arrival at the University of Chicago, I was lucky enough to meet William Julius Wilson, the eminent scholar of urban poverty. He made an unforgettable impression on me: he was thoughtful, choosing his words carefully, and it was obvious that Id learn a lot if I simply paid attention. My fathers counsel echoed in my head: Listen to Bill, follow his advice, always work harder than you need to.

Throughout the course of my graduate studies, I ran into many obstacles, and Bill was always there to guide me. I brought him many typical grad-student dilemmas (How should I prepare for my exams?) and some that were less typical (If I find out that the gang plans to carry out a murder, should I tell somebody?). More than once I tested his patience; more than once he told me to stop going to my field site until things cooled off. I am one in a long line of students who have benefited from Bill Wilsons tutelage. For his patient direction, I remain grateful.

None of this is meant to discount the role that my mother has played in my life and career. She is the most caring and thoughtful person I have ever known; her voice always rang in my head when I needed to get around a roadblock. Thanks, Mom.

I can recall the initial conversations with my sister, Urmila, when I signed up to write this book. I was nervous, while she was overjoyed. She has always productively channeled her enthusiasm by keeping me honest and mindful of those who are less fortunate and who may never benefit from my writings.

At the University of Chicago and at Columbia, Professors Peter Bearman, Jean Comaroff, John Comaroff, Herbert J. Gans, Edward Laumann, Nicole Marwell, and Moishe Postone guided me through difficult waters. Katchen Locke, Sunil Garg, Larry Kamerman, Ethan Michaeli, Amanda Millner-Fairbanks, David Sussman, Benjamin Mintz, Matthew McGuire, and Baron Pineda were ever supportive, whether with humor, advice, or a glass of wine. Farah Griffins writings inspired me to push on, Doug Guthrie encouraged me to pursue the venerable path of public sociology, and Eva Rosen read drafts diligently and is on her way to becoming an outstanding sociologist.

I never would have written this book if I hadnt met Steven Levitt, an economist who took an interest in my fieldwork. Over dinner one night at the Harvard Society of Fellows, Steven and I spent hours trying to connect the worlds of economics and sociology. To this day Steven remains a close collaborator and friend. I couldnt have attempted this act of hubris without his encouragement. Steven kindly introduced me to Suzanne Gluck, who helped shepherd me through the byzantine world of trade publishing. Suzanne is one of the wisest souls I have ever met. At Penguin, Ann Godoff has been a pleasure to work with, and I hope this is the first of many journeys under her stewardship.

In writing this book, I drew on the intellectual gifts and emotional sustenance of my close friend Nathaniel Deutsch. I pulled Nathaniel away from his precious daughter, Simona, on many occasionsto rant, cry, or just throw up my hands. Nathaniel, I may never be able to return the favor, but I will certainly make sure Simi knows how kind you have been.

To Stephen Dubner, I owe an inexpressible debt. Stephen had the unenviable task of helping me put my thoughts on paper. It was not always easy for me to visit my past, and Stephen listened to my meanderings patiently, offering the right amount of criticism and feedback. I doubt that Stephen thinks of himself as a teacher, but he is one of the best.

I remain especially grateful to the tenants of the Robert Taylor Homes for letting me into both their apartments and their lives. Dorothy Battie has been a close friend, and Beauty Turner and the staff at the Residents Journal newspaper have given of their time generously.

I still feel guilty about all those years that I let J.T. think I would write his biography. I hope that he at least reads these pages someday. While a lot of it is my story, it plainly could never have happened without him. He let me into a new world with a level of trust I had no reason to expect; I can only hope that this book faithfully represents his life and his work.

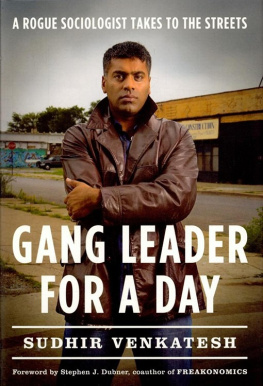

About the Author

Sudhir Venkatesh is a professor of sociology and African-American studies at Columbia University in New York. He has written extensively about American poverty. He is currently working on a project comparing the urban poor in France and the United States. His writings, stories, and documentaries have appeared in The American Prospect,This American Life, and The Source and on PBS and National Public Radio.

AUTHORS NOTE

Many of the names and some of the identities in this book have been changed. I also disguised some locations and altered the titles of certain organizations. But all the people, places, and institutions are real; they are not composites, and they are not fictional.

Whenever possible, I based the material on written field notes. Some of the stories, however, have been reconstructed from memory. While memory isnt a perfect substitute for notes, I have tried my best to reproduce conversations and events as faithfully as possible.

ONE

How Does It Feel to Be Black and Poor?

During my first weeks at the University of Chicago, in the fall of 1989, I had to attend a variety of orientation sessions. In each one, after the particulars of the session had been dispensed with, we were warned not to walk outside the areas that were actively patrolled by the universitys police force. We were handed detailed maps that outlined where the small enclave of Hyde Park began and ended: this was the safe area. Even the lovely parks across the border were off-limits, we were told, unless you were traveling with a large group or attending a formal event.

It turned out that the ivory tower was also an ivory fortress. I lived on the southwestern edge of Hyde Park, where the university housed a lot of its graduate students. I had a studio apartment in a ten-story building just off Cottage Grove Avenue, a historic boundary between Hyde Park and Woodlawn, a poor black neighborhood. The contrast would be familiar to anyone who has spent time around an urban university in the United States. On one side of the divide lay a beautifully manicured Gothic campus, with privileged students, most of them white, walking to class and playing sports. On the other side were down-and-out African Americans offering cheap labor and services (changing oil, washing windows, selling drugs) or panhandling on street corners.