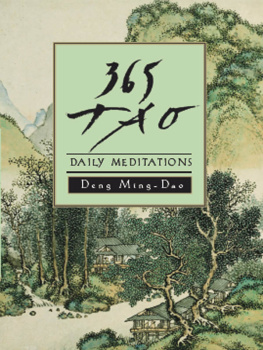

BOOKS BY DENG MING-DAO

The Chronicles of Tao

The Wandering Taoist

Seven Bamboo Tablets of the Cloudy Satchel

Gateway to a Vast World

Scholar Warrior

365 Tao

Everyday Tao

Zen: The Art of Modern Eastern Cooking

The Living I Ching

The Lunar Tao

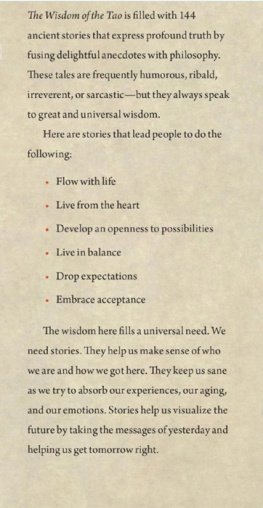

The Wisdom of the Tao

Each Journey Begins With a Single Step

Grateful acknowledgment to Professor Aimin Shen, Hanover College, for her close reading.

Copyright 2019 by Deng Ming-Dao

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

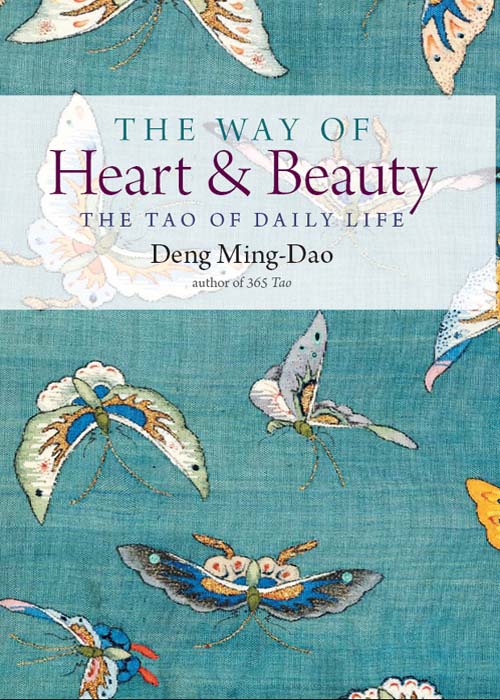

Cover design by Deng Ming-Dao

Cover photograph: Woman's Sleeveless Jacket with Butterflies. Late 19thearly 20th century, China; Tapestry-woven silk and metallic thread (kesi); 27 36 in. (68.6 91.4 cm); Gift of Florance Waterbury, 1945; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Floral image by Qian Weicheng (17201772); album, ink on paper; 27.4 37 cm; National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

Interior design by Deng Ming-Dao

Typeset at Side By Side Studios, San Francisco

Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc.

Charlottesville, VA 22906

Distributed by Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

www.redwheelweiser.com

Sign up for our newsletter and special offers by going to

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter.

ISBN: 978-1-57174-839-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Printed in the United States of America

M&G

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

We live in an era rich with more information than any previous period in the world's history. Each day, we consume an abundance of news, entertainment, and communication. We investigate other cultures, world views, theories, philosophies, and religions. When we're faced with serious questions, we rightly look into a vast stream of knowledge for answers, and soon we will find references to Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism.

Over thousands of years, these traditions have examined how to find our proper place in nature, make the right decisions, be moral leaders, face good and bad fortune, treat other living creatures, respect the earth, and view life and death calmly. The process began with those called the Early Kings. It continued with great philosophers such as Laozi, Zhuangzi, Confucius, and Buddha. They directed us toward a brilliant way that lasts to the present.

We certainly need the answers that path offers. We may be occupied with important issues and we may prize innovation, but we must still grapple with the same personal matters that have puzzled every generation and every people before us. War, starvation, inequality, corruption, human rights, emotions, relationships, family concerns, and mortality confront us all. The signposts that the ancients left unselfishly for us can point us to the best way.

The sages urge us to walk in the center of the road rather than to lurch side to side, to avoid being lost on detours, and to reject the manipulations of power-hungry autocrats. They urge us to embrace simplicity, compassion, honest livelihoods, and spirituality. It's all there for us to read for ourselves.

That raises three issues. First, the classics are unevenly translated. Some have been rendered repeatedly, while others are not well-known. This implies that some might be more popular, but the fact is that they are more easily translated. Second, the language itself is old and poetic. Chinese words are ideographs and ancient grammar was not always linear, which leads to multiple interpretations. Each word therefore has many meanings that shift with the context. This detail delighted those writers who loved rhymes, wordplay, and expansive allusions. The language became incredibly concise and intense: occasionally, it takes two lines in English plus a glossary to reasonably translate a few words from the Chinese. Third, most of the classics have been previously translated with a dry and lofty tonewhen they were just as often emotional records and incisive insights into the human condition.

In order to address that, this book looks at a number of classics, juxtaposing them so that they can comment on each other. This allows the reader to interpret them directly, and to benefit from the full range of viewpoints. The translation has been kept as spare as possible to retain the flavor of the originals.

The passages in this book pertain to two words: heart and beauty. These two words are important precisely because they're challenging to translate. The Chinese word for heart means both heart and mind simultaneously, and the word for beauty describes a range of ideas from pleasurable sights to the highest excellence.

The ideograph for heart is a picture of a human heart: xin,  . It means heart, mind, intention, center, core, intelligence, and soul all at once. The ideograph for beauty is mei,

. It means heart, mind, intention, center, core, intelligence, and soul all at once. The ideograph for beauty is mei,  , meaning beautiful, satisfactory, good, or pleasing. It combines the sign for ram,

, meaning beautiful, satisfactory, good, or pleasing. It combines the sign for ram,  , over a glyph,

, over a glyph,  , that means big, vast, great, large, or high. Perhaps we might picture a flock of sheep in a pastoral setting as the symbol of beauty. In earlier times, however, older forms of the word showed a feathered headdress on a person. Beauty was a shaman crowned with featherssomeone dancing with all their heart.

, that means big, vast, great, large, or high. Perhaps we might picture a flock of sheep in a pastoral setting as the symbol of beauty. In earlier times, however, older forms of the word showed a feathered headdress on a person. Beauty was a shaman crowned with featherssomeone dancing with all their heart.

Translators usually choose mind for heart, and they often give some social or moral equivalent for beauty. They ask a reader to remember the multiple meanings, but subliminally, it still matters if we're only reading mind. To propose just rendering heart instead may be just as difficult, but reading heart and beauty gives the wisdom a greater impact: we see the feeling behind the lofty thoughts.

We often say, My heart wants one thing, but my mind wants another. This use of the word heart was no different in my childhood. I heard my grandmother thank others for favors, kindnesses, or gifts by saying, You have heart. If an aunt uttered something impolite, she quickly added, I didn't have heart, which meant, I didn't mean to hurt you. If an uncle complained about exhausting work, he said, I have no heart for this. When my father recounted what he silently thought during an argument, he told us, My heart said... When my mother counseled me to look at the truth of a situation, she would ask, What does your heart say? When disappointment and loss struck the family, I heard elders whisper, My heart aches. All this shows that we're neither referring to the mind as the thinking brain nor the heart as physical pump. We're referring to our total selves.

Next page

Contents

Contents . It means heart, mind, intention, center, core, intelligence, and soul all at once. The ideograph for beauty is mei,

. It means heart, mind, intention, center, core, intelligence, and soul all at once. The ideograph for beauty is mei,  , meaning beautiful, satisfactory, good, or pleasing. It combines the sign for ram,

, meaning beautiful, satisfactory, good, or pleasing. It combines the sign for ram,  , over a glyph,

, over a glyph,  , that means big, vast, great, large, or high. Perhaps we might picture a flock of sheep in a pastoral setting as the symbol of beauty. In earlier times, however, older forms of the word showed a feathered headdress on a person. Beauty was a shaman crowned with featherssomeone dancing with all their heart.

, that means big, vast, great, large, or high. Perhaps we might picture a flock of sheep in a pastoral setting as the symbol of beauty. In earlier times, however, older forms of the word showed a feathered headdress on a person. Beauty was a shaman crowned with featherssomeone dancing with all their heart.