Contents

Guide

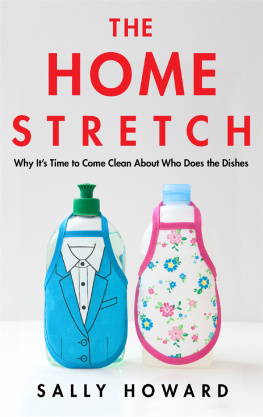

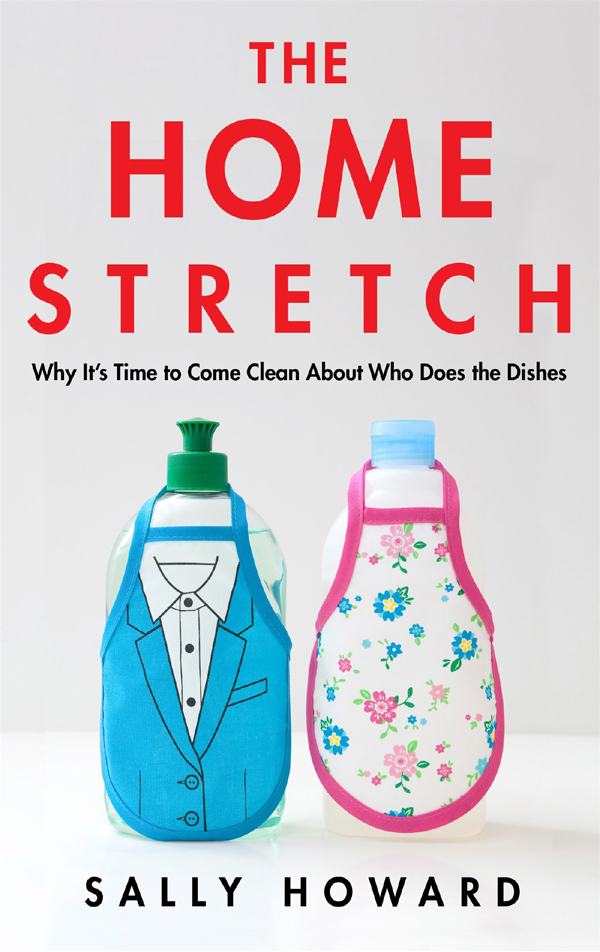

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Sally Howard, 2020

The moral right of Sally Howard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 78649 757 4

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 83895 056 9

E-book ISBN 978 1 78649 758 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Ginny and Mary

Contents

Introduction

A fter nine months of sobriety and two and a half months on a gruelling 24-hour regime of two-hourly baby feeds, I was on my first night out as a new mother: an office Christmas party. I had expressed the bottle of breast milk with the electric expresser that moistly exhaled, shoot-pffft-shoot-pffffttt, like a breathless retriever (Id grown to hate that machine). The sleeping bag was washed and laid beside the baby sleepsuit. Id blow-dried my weirdly thinning hair who knew fistfuls of hair fell out postpartum? squeezed my new moonscape of a midriff into a festive red dress, and left Leo in Tims charge.

I was two inches into an unpleasant but welcome glass of London-pub Pinot when the messages started to arrive.

When you say warm it up do you mean put it in boiled water? The whole bottle in boiled water? Or is boiled water too hot?

Does he wear these tiny trousers in bed? [picture enclosed] Or are these tiny trousers tights?

In the midnight confidences of early intimacy, my partner Tim and I would laugh about the honeydos. These were our parents generations wifely domestic instructions and corrections to their husbands: Honey do you think you could empty the bins? Honey do you mind putting the crumble in the oven? Tim amusedly speculated that his aunts honeydos had deskilled a male family member to the extent that, when left to fend for himself, he would spend half an hour trying to remember whether peas were cooked with water or without, before ordering a takeaway balti.

Somehow, despite my feminist ambitions of an egalitarian division of domestic labour, here Tim and I were, a few months into parenthood, with an expectation that Id keep the domestic show on the road by knowing what was needed and when, and how these needs could be met. I knew the temperature the milk had to be. I knew if we owned enough of those maddeningly poppered babygros in the right size and if theyd been washed. I knew what wed feed Leo for his first meal, that it couldnt include salt or honey, and where he stood on the baby-weight percentiles (92nd down from 4th at birth, as a prize marrow to a prawn). I knew to whom we owed thank-you cards for that teetering pile of too-small bootees (childless friends always buy you bootees). In short, both the emotional and mental labour of keeping the family alive and thriving fell on my (aching) shoulders.

Its a strange feature of new motherhood that your own childhood is suddenly, vividly brought back to life. And so it was for me: snapshots of my smiling mother handing an earthenware pot of casserole through the kitchen hatch, and of swift embraces and gentle scoldings. Awake in the small hours, scrolling through the list of social obligations to my partners family and friends, or pureeing endless sweet potato for Leos weaning menu because my partner declared himself incapable of performing a culinary task without a recipe to follow, I wondered how different the emotional and domestic battles I faced were to my mothers and grandmothers.

What was so perplexing was that, on the face of it, Tim and I had entered into parenthood with a genuine willingness to share domestic tasks equally. Wed talked about our ambition of being a truly fair family, in which chores would be allotted equably rather than with an eye to gendered norms. I took comfort in Tims long pre-parental record of knocking out Jamie Oliver 30-minute meals in 45 minutes. He cleaned more assiduously than I did and attended to some domestic touches Id never notice: smoothing the bottom creases from the sofa cushions at night, for example, and moving the newly bought provisions to the back of the fridge so we didnt end up with three circulating tubs of half-eaten Lurpak.

Yet, somewhere along the line, Tim had resigned domestic administration to me. And somewhere along the line, barely noticing it, I had accepted that this was the natural order of things. I was the one with whom the domestic buck stopped, however many bottles Tim sterilized, or milk stains he sponged.

It was during a bleak night of insomnia brought on by six months of shifting night feeds that I discovered an essay written by Judy Brady for Gloria Steinems Ms. magazine in 1971. Titled I Want a Wife, it spoke poetically of the invisible role women/wives/mothers perform in the smooth running of family lives. Brady opens by explaining that a newly divorced male friend is on the hunt for a brand-new wife, and it had occurred to her that she could do with a wife of her own. With a wife, she could return to her studies, become better qualified, get a new job and become financially independent, while her wife committed all of her energies to making Bradys life as pleasant as possible.

I want a wife who knows that sometimes I need a night out by myself

I want a wife who will take care of the details of my social life [and] the baby-sitting arrangements

I want a wife to keep track of the childrens doctor and dentist appointments

I want a wife who takes care of the children when they are sick

My wife must arrange to lose time at work and not lose her job.

This 47-year-old essay, it struck me, had barely aged. In it I heard the voices of the harried women Id met through mothering classes whod found themselves sidelined in the workplace after maternity leave; friends whod been forced into freelance work to keep up with their childrens schools growing demands for attending concerts and fundraisers and, in the words of a North London single-mum acquaintance, knocking up fucking Victoria sponges with a days notice. Women who juggled these swelling domestic demands with all the finesse of a drunk unicyclist and had slowly, inexorably, begun to despise their other halves. Bradys essay speaks to domestic labour, but also the smoothing and facilitating labour that women in heterosexual unions disproportionately undertake. To be Bradys wife is to be a sponge: wives absorb every problem, obstacle and distraction, and ensure that a husband/partners path to success and self-fulfilment is set in a smooth, straight line.