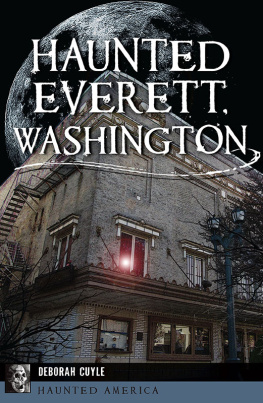

Portrait of Everett by George P. A. Healy, c. 184243

Acknowledgments

In addition to gainful employment at Brigham Young University during the years of work on this book, I am grateful for those who have helped fund it. At BYU, those entities include the College of Family, Home, and Social Sciences; the Department of History; the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies; and the General Education and Honors Programs. Further funding came from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and the American Antiquarian Society. For help both financial and logistical in getting me access to Everett documents in Provo, I thank Paul Kerry as well as the Interlibrary Loan staff at Harold B. Lee Library at BYU.

For enormously helpful and encouraging readings of the whole manuscript, I am grateful to James Brewer Stewart, John Brooke, Michael Morrison, and Elise Peterson. For reading and making useful comments on parts of the manuscript, my thanks go to Michael E. Woods, Douglas Egerton, Nicholas Wood, Francois Furstenberg, Scott Heerman, Edward Rugemer, Corey Brooks, John Craig Hammond, Nicholas Mason, Jeffrey Kerr-Ritchie, Randall Miller, David Waldstreicher, Elizabeth Varon, Conrad Wright, Paul Kerry, Gary Gallagher, and Stacey Robertson. For helping me talk through earlier iterations of and issues with this book, I thank Fred Blue, Daniel Walker Howe, and Chuck Grench.

This book is dedicated to my wife and daughters, for whom I would willingly buckle a knapsack to my back and march anywhere.

APOSTLE of UNION

Introduction

In December 1859, with John Browns raid on Harpers Ferry having shaken his beloved Union once again to its core, Edward Everett rose to address a mass meeting in his hometown of Boston. This audience knew Everett not only for his long career as a scholar and politician but also for his most recent career as a traveling orator for the Union. Throughout the late 1850s, Everett had journeyed to every section of the nation delivering an oration titled The Character of Washington to packed houses, donating the proceeds to save the first presidents Mount Vernon estate as a shrine to the Union. Thus when he stepped to the podium of this meeting called to demonstrate Bostonians attachment to the Union, the throng paid him every demonstration of respect and enthusiasm. Everetts predominant purpose that day, as with his Mount Vernon activities, was to inculcate the blessings of the Union, consecrated as they were by the memory of our Fathers who gave it to us: Precious legacy of our fathers, it shall go down, honored and cherished to our children. Generations unborn shall enjoy its privileges as we have done, and if we leave them poor in all besides, we will transmit to them the boundless wealth of its blessings! Such filial appeals had an electric effect. A newspaper reporter present remarked on the close attention, the earnest feeling, which this vast crowd manifested, including the frequent tears in the eyes and on the faces of multitudes touched by a common sympathy, as some patriotic emotion was awakened by the sentiments of the several speakers. Indeed, attendees hearts were swelling with pent-up emotions, longing to find adequate expression.

A year and a half previous, he had taken this Unionist gospel into the belly of the secessionist beast, Charleston, South Carolina, and had received a similarly rapturous response. Reports of his performance of the oration in Augusta, Georgia, beat Everett to Charleston, and they described how his auditors in that town had not yet recovered from the spell which was thrown around us by this mighty magician. Indeed, words failed when one attempted to convey the

Such public demonstrations of emotion in such apparently opposite and antagonistic places as Boston and Charleston on the eve of the Civil War cry out for exploration. They indicate both the strength of the Union and that this strength lay primarily in the hearts of antebellum Americans. As the content of Everetts speeches suggested, the Union packed such an emotive punch for most white antebellum Americans because of its connection to the revered Revolutionary Fathers and because it embodied the Revolutions legacy of political rights that were rare in the nineteenth-century world. Indeed, for them the term Union connoted a voluntary confederation rather than a nation cemented by force. Others might calculate the value of that compact and make decisions about slavery based on profit and loss considerations. But these patriots stood by a Union of the heart, not of the pocketbook.

Indeed, by then Everett had pursued an unusually long, complex, and high-profile career at the crossroads of slavery, a culture of reform, and nation-building in American politics. He had been much in the public eye as an orator, politician, scholar, and diplomat. His thinking, writing, and speaking about the nature and value of the American Union stretched from the death of George Washington to the presidency of Abraham Lincoln. The successes, failures, and evolution of his vision of how vexing political questions, includingbut far from limited toslavery, should interact with the sacred Union provide an unusually valuable window on the ebbs and flows of Unionism as a political force across this long period. The themes Everetts career illuminates dictate the parameters of this volume: it will have its hands full with presenting a political biography focused on the mans public life. His literary efforts and his private life will come in only as they shed light on that public career.