This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002.

PREFACE

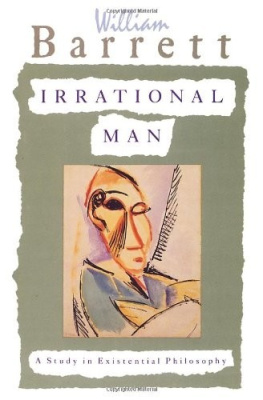

T HE purpose of this book is exposition, not criticism nor advocacy. There have been enough popular accounts of the general ideas of existentialists. It is time to discriminate between these thinkers; they are not exponents of a school, and yet not the least impressive thing about their highly individual thought, separated by age, nationality, and temperament, is the interrelatedness of their thinking: they lead into each other; they form a natural family; each throws light on the others, and together they develop the content of certain common themes. For this reason, the book should be read as a whole.

The excuse for trying to get these writers a hearing in English in summary form is that the contemporary ones are not yet fully translated and are voluminous and not easy to read. These studies may serve as an introduction and as a clue. The final essay is not intended as a critical assessment; it is still interpretative, and designed to remove some of the prevalent misunderstandings and dispose of some of the fanciful criticisms.

Although these studies appeal to the reader to take each thinker individually on his merits and not as the exponent of a school, it is permissible to try to see the movement in the grand perspective of human thought. It appears to be reaffirming in a modern idiom the protestant or the stoic form of individualism, which stands over against the empirical individualism of the Renaissance or of modern liberalism or of Epicurus as well as over against the universal system of Rome or of Moscow or of Plato. These are permanent types of thought and attitude, deeper than any formal doctrine or belief. As pure types, they show excesses and deficiencies which the various forms of compromise escape; and they show dramatic qualities which only pure forms can have. If this analysis is sound, existentialism is not (as some think) an hysterical symptom of the irrationalism associated with the violence and disintegration of our time: it is a contemporary renewal of one of the necessary phases of human experience in a conflict of ideals which history has not yet resolved. If it has this order of importance, it is worth serious attention.

Finally, the general reader who is interested enough to want to acquaint himself with existentialism should be told at the outset that there is nothing in this book which he cannot understand if he really wants to. There are difficulties, but they are not technical, and they are likely to oppress the philosopher even more than the general reader.

H.J.B.

CONTENTS

I

SREN KIERKEGAARD

(18131855)

I

K IERKEGAARD pertinaciously challenged his countrymen on their pretensions to Christian faith and made the vanity of their German culture the constant target of his Attic wit. The seriousness of his sustained campaign sealed his separation from normal domestic happiness and from the fellowship of his generation, condemned him to loneliness and a tragic role. Like a solitary fir tree egoistically separate and pointed upward I stand, casting no shadow, and only the wood-dove builds its nest in my branches. Whether his was a case of the prophet without honour in his own country, or just a case, is a difference of opinion between his many disciples and admirers in the world to-day and others who having neither sympathy nor patience either with him or with his ideas explain both from the sufficient evidence of his neurosis and its cause. At least the disciples have read and studied him, and it is safe to say that nobody can read him to any extent without being permanently impressed by the exceptional intellectual and literary power of the man and the genuine totality of his Christian inwardness. He was physically deformed, he was crippled by a sense of guilt, he was a genius in a market town: this was a mixture that had to explode in excess, an extreme concentration or an extreme dissipation. The absolute disjunction of his first book Either-Or, which remained the clue to all his thinking, was not merely nor mainly the slogan of his attack upon the Hegelian principle of mediation and synthesis, but was rooted, and consciously rooted, in his personal need for tension, passion, sacrifice, individuality. Between the absolute of concentration and of dissipation the choice was inevitably certain: he proposed to think and will one thing, and became a man set apart, a sacrifice, a personality, whose challenge to his time was carefully planned and copiously and energetically worked out to a conclusion in his active life, with effects that still reverberate in theology and philosophy; whilst in his inner orientation he became a man turned away from this world who historically speaking died of a mortal disease, but poetically speaking died of longing for eternity.

Philosophical Fragments (1846) are the central works in the development of Kierkegaards life-purpose. Together, the two books present as directly and methodically as can be expected the philosophical thinking of a man whose method is indirect and whose philosophy is not a system. The titles are in themselves characteristic hits at the elaborate system established under the rule of Hegel (the System). Existentialism begins as a voice raised in protest against the absurdity of Pure Thought, a logic which is not the logic of thinking but the immanent movements of Being. It recalls the spectator of all time and of all existence from the speculations of Pure Thought to the problems and the possibilities of his own conditioned thinking as an existing individual seeking to know how to live and to live the life he knows. Kierkegaard imagines how Socrates would tease Hegel, with dialectical skill interrupting his flights and keeping him down to earth. His strength against Hegel at this time of the tremendous swell and boom of Hegels reputation on the Continent derives from the sharp pangs of his own need for something to live by. In his student days, having rejected Christianity, he devoted himself to Hegel.