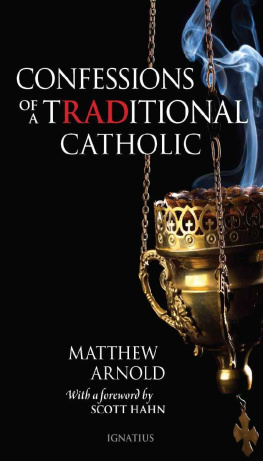

The Cultural Production of Matthew Arnold

Antony H. Harrison

THE CULTURAL

PRODUCTION OF

MATTHEW ARNOLD

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

www.ohioswallow.com

2009 by Ohio University Press

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper

16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harrison, Antony H.

The cultural production of Matthew Arnold / Antony H. Harrison.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8214-1899-4 (alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8214-1900-7 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Arnold, Matthew, 18221888Criticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PR4024.H36 2009

821'.8dc22

2009033165

For Penn, who rejuvenates me,

and Anne, who restores me

RATIONALE

The last truly important critical book devoted to Matthew Arnolds poetry was David Riedes Matthew Arnold and the Betrayal of Language, published at the centenary of Arnolds death. That he is susceptible to such manipulation results in part from the deliberate mystifications that inhabit his poetry and prose. But it is also the case that Arnold, as himself a symbolic figure within the field of cultural production, has always been under construction.

The several entendres of this books title will, doubtless, be lost on few readers: the manufacture of Matthew Arnold (as an eminent poet and the preeminent critic of his generation) by various nineteenth- and twentieth-century intellectual fields of force together with the extraordinarily influential textual creations of Matthew Arnold (both his own and those of admirers who canonized him) constitute a remarkable historical spectacle orchestrated by a host of powerful Victorian cultural institutions (including, among others, Oxford University, the publishing industry, the national education bureaucracy, and the civil list pension commissioners). The chapters in this book begin to investigate these constructions by situating Arnolds poetry in various contexts that partially shaped it. Analysis of what for Arnold were culturally privileged pressures on his work provides helpful perspectives on fault lines in both his foundational values and his poetic expression of them, and it thus reveals much about the fractured political, social, amatory, and literary underpinnings of guiding middle-class intellectuals in Victorian England. Such analysis also revises our understanding of the formation of the elite (and elitist) male literary-intellectual subject during the 1840s and 1850s, as he attempts self-definition and strives simultaneously to move toward a position of ideological influence on intellectual institutions that were contested sites of economic, social, and political power in his era. (These institutions would include, for instance, the schools and universities, the Anglican Church, the publishing industry, and the law.)

The particular contexts I attend to here are political (from the dual threats of European revolutions in 1848 to that of Chartism at home); social (from the sometimes-histrionic nostalgia for all things medieval in Arnolds era to the midcentury fascination with gypsies, reflected both positively and negatively in the law and other Victorian cultural texts); literary (from Arnolds poetic responses to precursors such as Wordsworth and Keats to his attacks on contemporaries such as Alexander Smith); and finally, those of gender (from the silencing of the female voice in his poetry to its My frequent procedure with this project is to reopen discussion of selected works by Arnold in order to make visible some of their crucial sociohistorical, intertextual, and political components. Only by doing so, I would argue, can we ultimately view the cultural work of Arnold steadily and... whole but also in a fashion that eschews this mystifying and literally prejudicial premise of all Arnoldian inquiry, which, by the early twentieth century, had become wholly naturalized in the academy as ideology.

As will be apparent to readers, the methodologies I make use of in these explorations of cultural contexts that inflect (if they do not determine) important ideological aspects of Arnolds poetry are largely derived from recent historicist, sociological, deconstructive, and feminist criticism. Pierre Bourdieu is an especially important theorist guiding the direction of my analyses. In The Field of Cultural Production, Bourdieu extends his previous work as a sociocultural theorist to demonstrate how a special variety of power relations is inevitably instantiated in the interactions among authors and texts that aspire to cultural dominance. Fundamental to Bourdieus theory is the premise that the literary and artistic field is contained within the field of power, while possessing a relative autonomy with respect to it, especially as regards its economic and political principles of hierarchization.quirky) and thereby to preserve a very high level of autonomy. As Bourdieu contends, because it is a good measure of the degree of autonomy, and therefore of presumed adherence to the disinterested values which constitute the specific law of the field, the degree of [immediate] public success (39) is no measure (and indeed may be an inverse measure) of power in the field, in this case a field in which the most advantageous and desirable power is symbolic: that is, cultural capital.

The present book attempts a relatively simple argument, distilled from analyses of the contexts for Arnolds work discussed above: the most frequent strategies deployed in Arnolds poetic productions (and in much of his prose)strategies that eventually yield his own cultural dominanceare (1) self-marginalization, (2) the (fraudulent) suppression of his works true origins, and (3) ideological mystification (either through a process of recentering or shifting apparent ideological positions, or through an implicit or sometimes explicit denial of ideological content or aims). Whether eliding the true historical contexts of poems generated from his immersion in English and European politics during the late 1840s; reconceptualizing the culturally pervasive penchant for all things medieval in the long nineteenth century; appropriating and redirecting (as cultural critique) dominant elements in the work of Keats, the so-called Spasmodic poets, or the phenomenally successful women poets of sensibility (while simultaneously eschewing such influences); or implicitly identifying with gypsy figures that emerge as the central trope in many of his major poems, Arnold disingenuously positions himself as an outsider. He presents competing positions or figures, as well as the social or political or aesthetic values they embody, as lamentably dominant in a not-quite-irredeemable culture. And by doing so consistently and repeatedly over the course of his career, Arnold accrued increasing and finally indomitable cultural capital. By 1939, Lionel Trilling could go so far as to describe Arnolds reputation as a mythopoeia (Matthew Arnold, 9) and the man himself as one of Bernard Shaws ideal

Theories of the cultural production of texts formulated by Bourdieu and other late-twentieth-century social and philosophical thinkers I cite in the chapters that follow liberate the literary historian to see beyond traditional critical wisdom and are especially helpful in coming to terms with a writer such as Arnold whose successful poetic, rhetorical, and ideological strategies enabled his work to attain an astonishing level of influence on Anglo-American cultural values that has only in the past two decades begun to wane. It is the backgrounds to such influence, specifically as these emerge from (sometimes unexpected) historically situated readings of his poetry, that I explore in this book.

Next page