Bruce T. Moran - Paracelsus

Here you can read online Bruce T. Moran - Paracelsus full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Reaktion Books, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Paracelsus

- Author:

- Publisher:Reaktion Books

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Paracelsus: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Paracelsus" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Paracelsus — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Paracelsus" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PARACELSUS

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Series Editor: Franois Quiviger

Already published

Blaise Pascal: Miracles and Reason Mary Ann Caws

Caravaggio and the Creation of Modernity Troy Thomas

Donatello and the Dawn of Renaissance Art A. Victor Coonin

Hieronymus Bosch: Visions and Nightmares Nils Bttner

Isaac Newton and Natural Philosophy Niccol Guicciardini

John Evelyn: A Life of Domesticity John Dixon Hunt

Leonardo da Vinci: Self, Art and Nature Franois Quiviger

Michelangelo and the Viewer in His Time Bernadine Barnes

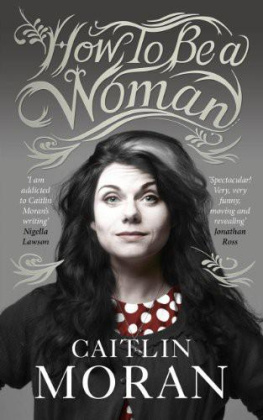

Paracelsus: An Alchemical Life Bruce T. Moran

Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer Christopher S. Celenza

Pieter Bruegel and the Idea of Human Nature Elizabeth Alice Honig

Raphael and the Antique Claudia La Malfa

Rembrandts Holland Larry Silver

Titians Touch: Art, Magic and Philosophy Maria L. Loh

An Alchemical Life

BRUCE T. MORAN

REAKTION BOOKS

For Ben and Bertie, who love to wander and explore

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2019

Copyright Bruce T. Moran 2019

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789141764

COVER: Anonymous, undated portrait of Paracelsus (after a 16th-century engraving), oil on wood. Private collection (photo Heritage Images/Fine Art Images/akg-images).

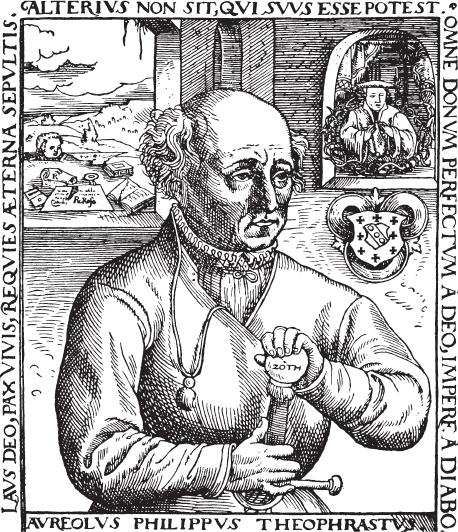

1 Woodcut portrait of Paracelsus by an anonymous artist, c. 1567.

ones! Just bones. Whoever ransacked Salzburgs prominent castle, the Hohensalzburg Fortress, in the days following the American occupation of the city at the end of the Second World War must have been very disappointed, if not dismayed. It was, after all, treasure, not bones, that he was looking for. The location looked promising and pointed to a real prize. The intruder found a small door in a room, the castles room number thirteen, where precious objects had been kept, and behind it, set down in a shaft, rested a wooden crate. The crate, filled with shavings, contained a metal box. Surely this was it, something worth a fortune. But then, bones! Just bones.

ones! Just bones. Whoever ransacked Salzburgs prominent castle, the Hohensalzburg Fortress, in the days following the American occupation of the city at the end of the Second World War must have been very disappointed, if not dismayed. It was, after all, treasure, not bones, that he was looking for. The location looked promising and pointed to a real prize. The intruder found a small door in a room, the castles room number thirteen, where precious objects had been kept, and behind it, set down in a shaft, rested a wooden crate. The crate, filled with shavings, contained a metal box. Surely this was it, something worth a fortune. But then, bones! Just bones.

In Salzburg in 1945, bones in a box did not make great plunder, so the pillager tossed them aside. When this was noticed soon thereafter, the castles curator knew what he had to do to keep the bones out of the wrong hands. According to one account, he buried them, this time under a pile of rubble in the castles basement. In another, he took them home to his apartment and hid them. Maybe he did both. When things were safer, they could once again come to light. These were, after all, not just any bones, but bones that had once belonged to one of the most extraordinary characters of the European Renaissance, a physician, alchemist and religious philosopher named Theophrastus von Hohenheim (14931541), who later became known as Paracelsus (a Latinized reference to his German name literally high, or perhaps alpine home or, as some others would allege, a claim to being above or beyond Celsus, the first-century AD Roman physician).

Paracelsus had died in Salzburg in September 1541, several days after dictating his last will and testament while sitting on a travellers cot at an inn called The White Rose. He wanted to be buried in the cemetery of a local church, St Sebastian. The bones have been at St Sebastian, with brief intermissions, ever since. At first they rested outside the church and then, in the mid-eighteenth century, when the church was rebuilt and enlarged, were transferred to a new monument, a marble pyramid in the churchs vestibule. The monument had a little door, and Paracelsus box of bones could be, with proper permission, easily removed. Generations of scholars have been unable to keep their hands off them. An examination in the nineteenth century suggested a suspicious death, indeed murder. More recent examinations have suggested that Paracelsus may have been intersex: the pelvis appeared characteristically female. Whatever the truth of the latter claim, the first is certainly false. Damage to the skull, considered by some to have been the result of a blow to the head, occurred, we now know, after his bodys interment. The real cause of his death remains uncertain, but a toxic level (ten times the normal amount) of mercury found in his bones, the result of long exposure, suggests a contributing factor.

Paracelsus left behind not just bones but texts, and like the examination of physical remains, the analysis of his What we dont know, we sometimes invent. He becomes a lonely genius whose ideas are far ahead of their time; a Romantic hero defying convention and established authority; a Renaissance magician; a martyr of natural science; a religious militant; a Utopian rebel and an advocate for social change. As a physician, he gets imagined as a precursor of modern medicine, one of the many fathers of enlightened medical practice, or as a forerunner of holistic approaches to healing. He is transformed in portraits, literature and film and at one point gets turned into an icon of mass ideology, refashioned, during the Nazi era, as a German national idol. No wonder, then, that shortly before the bombs started falling on Salzburg, his bones were once again removed from their pyramid tomb and carried up the hill for safekeeping in room number thirteen of the Salzburg castle.

In Paracelsus, we meet mystery, magic, craft and profound insight. But we can only really know him on his own terms. The modern world has become too precise in defining what belongs to medicine and science to help much in overcoming the perceived paradox of Paracelsus: namely, that one of the most important figures during the Renaissance to argue for changes in the way the body was understood, nature studied, disease defined and new therapies devised was himself moved by mystical speculations, an alchemical view of nature and a view of creation that required human beings to complete what a divine creator had begun. We have to take off our twenty-first-century spectacles to keep him in sight. Only then does the worth and relevance of what he did come into view, and only then can we recognize how an amalgam of characteristics made him appear so eccentric and dangerous to his contemporaries.

Part of what makes Paracelsus unique is his embrace of what, to many, appeared to be opposites. He combined practices that were magical and empirical, scholarly and folk, learned and artisanal. He knew Latin (the language of scholars) but wrote and lectured in German. He read ancient medical texts and then burned the best of them in a public display of reproach. The most important text for any physician, he argued, was not one found in a library. Although raised in the Catholic faith, he was anti-papal, shared many views in common with Reformation theologians and believed devoutly in a female deity, picturing Mary as a the pre-existing spouse of God the Father within the Sacred Trinity. In addition, he challenged the habits of conventional learning and educated behaviour. He admired the know-how and insights of those who worked with their hands such as miners, bathers, alchemists, midwives and barber surgeons and he taught his students to learn the medical art not on the basis of an ancient medical canon, but from experience. He travelled constantly, was hardly ever in one place for long, and had a reputation for lingering in taverns and drinking to excess. He often wrote by means of dictation, and most of his books went unpublished during his lifetime. Magical, religious and scientific traditions merged in those writings, as did the subjects of alchemy, astronomy, philosophy and medicine. Those combinations produced theoretical reforms in regard to understanding the operations of the body, making medicines and curing illness that clashed with the theory and practice of traditional learning. He therefore made enemies, and the attacks of his rivals were pitiless: he was, according to them, no more than a peasant; he was not even a man since, they said, he had lost his testicles while herding geese as a boy; he dictated while in a drunken stupor in the middle of the night while thrashing about with his sword; and he made pacts with the Devil and practised the black arts. In defending himself Paracelsus gave as good as he got, mocking the ignorance of his accusers with a language that was rough, irreverent and often foul. He was not, he admitted, raised in silk garments, but had grown up wearing coarse cloth.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Paracelsus»

Look at similar books to Paracelsus. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Paracelsus and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.