W. B. Yeats - Rosa Alchemica

Here you can read online W. B. Yeats - Rosa Alchemica full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Kessinger Publishing, LLC, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Rosa Alchemica: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Rosa Alchemica" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Rosa Alchemica — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Rosa Alchemica" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

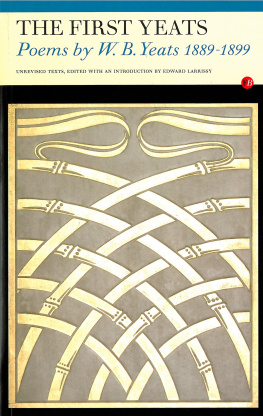

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rosa Alchemica, by W. B. Yeats#4 in our series by W. B. Yeats

Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check thecopyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributingthis or any other Project Gutenberg eBook.

This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this ProjectGutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit theheader without written permission.

Please read the "legal small print," and other information about theeBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included isimportant information about your specific rights and restrictions inhow the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make adonation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved.

**Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts**

**eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971**

*****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!*****

Title: Rosa Alchemica

Author: W. B. Yeats

Release Date: May, 2004 [EBook #5794][Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule][This file was first posted on September 1, 2002]

Edition: 10

Language: English

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROSA ALCHEMICA ***

Produced by Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

O blessed and happy he, who knowing the mysteries of the gods,sanctifies his life, and purifies his soul, celebrating orgies in themountains with holy purifications.Euripides.

It is now more than ten years since I met, for the last time, MichaelRobartes, and for the first time and the last time his friends andfellow students; and witnessed his and their tragic end, and enduredthose strange experiences, which have changed me so that my writingshave grown less popular and less intelligible, and driven me almostto the verge of taking the habit of St. Dominic. I had just publishedRosa Alchemica, a little work on the Alchemists, somewhat in themanner of Sir Thomas Browne, and had received many letters frombelievers in the arcane sciences, upbraiding what they called mytimidity, for they could not believe so evident sympathy but thesympathy of the artist, which is half pity, for everything which hasmoved men's hearts in any age. I had discovered, early in myresearches, that their doctrine was no merely chemical phantasy, buta philosophy they applied to the world, to the elements and to manhimself; and that they sought to fashion gold out of common metalsmerely as part of an universal transmutation of all things into somedivine and imperishable substance; and this enabled me to make mylittle book a fanciful reverie over the transmutation of life intoart, and a cry of measureless desire for a world made wholly ofessences.

I was sitting dreaming of what I had written, in my house in one ofthe old parts of Dublin; a house my ancestors had made almost famousthrough their part in the politics of the city and their friendshipswith the famous men of their generations; and was feeling an unwontedhappiness at having at last accomplished a long-cherished design, andmade my rooms an expression of this favourite doctrine. Theportraits, of more historical than artistic interest, had gone; andtapestry, full of the blue and bronze of peacocks, fell over thedoors, and shut out all history and activity untouched with beautyand peace; and now when I looked at my Crevelli and pondered on therose in the hand of the Virgin, wherein the form was so delicate andprecise that it seemed more like a thought than a flower, or at thegrey dawn and rapturous faces of my Francesca, I knew all aChristian's ecstasy without his slavery to rule and custom; when Ipondered over the antique bronze gods and goddesses, which I hadmortgaged my house to buy, I had all a pagan's delight in variousbeauty and without his terror at sleepless destiny and his labourwith many sacrifices; and I had only to go to my bookshelf, whereevery book was bound in leather, stamped with intricate ornament, andof a carefully chosen colour: Shakespeare in the orange of the gloryof the world, Dante in the dull red of his anger, Milton in the bluegrey of his formal calm; and I could experience what I would of humanpassions without their bitterness and without satiety. I had gatheredabout me all gods because I believed in none, and experienced everypleasure because I gave myself to none, but held myself apart,individual, indissoluble, a mirror of polished steel: I looked in thetriumph of this imagination at the birds of Hera, glowing in thefirelight as though they were wrought of jewels; and to my mind, forwhich symbolism was a necessity, they seemed the doorkeepers of myworld, shutting out all that was not of as affluent a beauty as theirown; and for a moment I thought as I had thought in so many othermoments, that it was possible to rob life of every bitterness exceptthe bitterness of death; and then a thought which had followed thisthought, time after time, filled me with a passionate sorrow. Allthose forms: that Madonna with her brooding purity, those rapturousfaces singing in the morning light, those bronze divinities withtheir passionless dignity, those wild shapes rushing from despair todespair, belonged to a divine world wherein I had no part; and everyexperience, however profound, every perception, however exquisite,would bring me the bitter dream of a limitless energy I could neverknow, and even in my most perfect moment I would be two selves, theone watching with heavy eyes the other's moment of content. I hadheaped about me the gold born in the crucibles of others; but thesupreme dream of the alchemist, the transmutation of the weary heartinto a weariless spirit, was as far from me as, I doubted not, it hadbeen from him also. I turned to my last purchase, a set of alchemicalapparatus which, the dealer in the Rue le Peletier had assured me,once belonged to Raymond Lully, and as I joined the alembic tothe athanor and laid the lavacrum maris at their side,I understood the alchemical doctrine, that all beings, divided fromthe great deep where spirits wander, one and yet a multitude, areweary; and sympathized, in the pride of my connoisseurship, with theconsuming thirst for destruction which made the alchemist veil underhis symbols of lions and dragons, of eagles and ravens, of dew and ofnitre, a search for an essence which would dissolve all mortalthings. I repeated to myself the ninth key of Basilius Valentinus, inwhich he compares the fire of the last day to the fire of thealchemist, and the world to the alchemist's furnace, and would haveus know that all must be dissolved before the divine substance,material gold or immaterial ecstasy, awake. I had dissolved indeedthe mortal world and lived amid immortal essences, but had obtainedno miraculous ecstasy. As I thought of these things, I drew aside thecurtains and looked out into the darkness, and it seemed to mytroubled fancy that all those little points of light filling the skywere the furnaces of innumerable divine alchemists, who labourcontinually, turning lead into gold, weariness into ecstasy, bodiesinto souls, the darkness into God; and at their perfect labour mymortality grew heavy, and I cried out, as so many dreamers and men ofletters in our age have cried, for the birth of that elaboratespiritual beauty which could alone uplift souls weighted with so manydreams.

My reverie was broken by a loud knocking at the door, and I wonderedthe more at this because I had no visitors, and had bid my servantsdo all things silently, lest they broke the dream of my inner life.Feeling a little curious, I resolved to go to the door myself, and,taking one of the silver candlesticks from the mantlepiece, began todescend the stairs. The servants appeared to be out, for though thesound poured through every corner and crevice of the house there wasno stir in the lower rooms. I remembered that because my needs wereso few, my part in life so little, they had begun to come and go asthey would, often leaving me alone for hours. The emptiness andsilence of a world from which I had driven everything but dreamssuddenly overwhelmed me, and I shuddered as I drew the bolt. I foundbefore me Michael Robartes, whom I had not seen for years, and whosewild red hair, fierce eyes, sensitive, tremulous lips and roughclothes, made him look now, just as they used to do fifteen yearsbefore, something between a debauchee, a saint, and a peasant. He hadrecently come to Ireland, he said, and wished to see me on a matterof importance: indeed, the only matter of importance for him and forme. His voice brought up before me our student years in Paris, andremembering the magnetic power ne had once possessed over me, alittle fear mingled with much annoyance at this irrelevant intrusion,as I led the way up the wide staircase, where Swift had passed jokingand railing, and Curran telling stories and quoting Greek, in simplerdays, before men's minds, subtilized and complicated by the romanticmovement in art and literature, began to tremble on the verge of someunimagined revelation. I felt that my hand shook, and saw that thelight of the candle wavered and quivered more than it need have uponthe Maenads on the old French panels, making them look like the firstbeings slowly shaping in the formless and void darkness. When thedoor had closed, and the peacock curtain, glimmering like many-coloured flame, fell between us and the world, I felt, in a way Icould not understand, that some singular and unexpected thing wasabout to happen. I went over to the mantlepiece, and finding that alittle chainless bronze censer, set, upon the outside, with pieces ofpainted china by Orazio Fontana, which I had filled with antiqueamulets, had fallen upon its side and poured out its contents, Ibegan to gather the amulets into the bowl, partly to collect mythoughts and partly with that habitual reverence which seemed to methe due of things so long connected with secret hopes and fears. 'Isee,' said Michael Robartes, 'that you are still fond of incense, andI can show you an incense more precious than any you have ever seen,'and as he spoke he took the censer out of my hand and put the amuletsin a little heap between the

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Rosa Alchemica»

Look at similar books to Rosa Alchemica. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Rosa Alchemica and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.