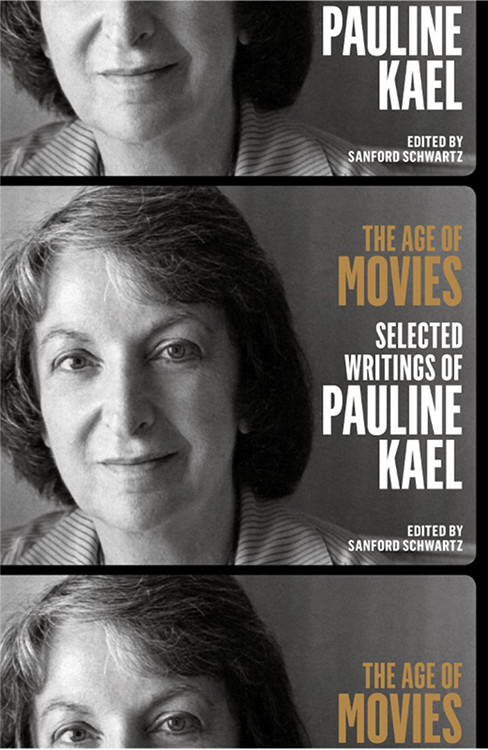

THE AGE OF

MOVIES

SELECTED

WRITINGS OF

PAULINE

KAEL

Edited by Sanford Schwartz

A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA

Copyright 2011 by Gina James.

Introduction copyright 2011 by Sanford Schwartz.

All rights reserved.

No part of the book may be reproduced commercially by offset-lithographic or equivalent copying devices without the permission of the publisher.

For sources and acknowledgments .

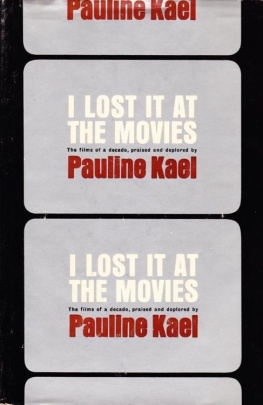

Material from I Lost it at the Movies and Going Steady is reprinted by permission of Marion Boyars Publishers.

The letters of Pauline Kael are reprinted courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

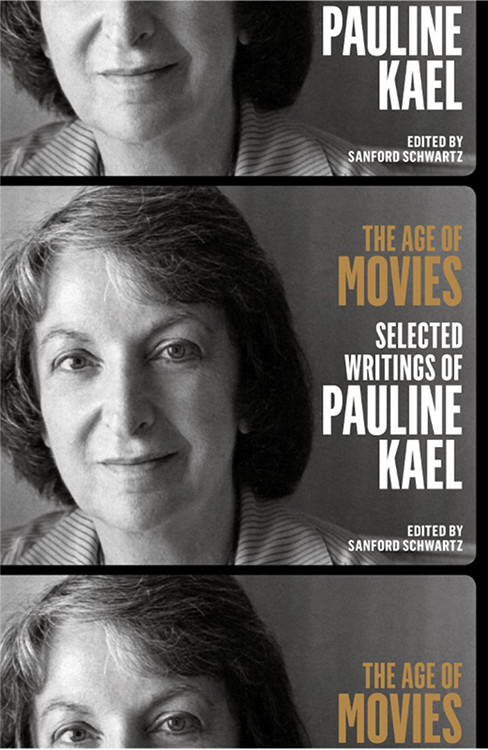

Frontispiece photograph copyright Jerry Bauer, Cannes, 1977

Distributed to the trade in the United States by Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

and in Canada by Penguin Books Canada Ltd.

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of Americas best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

If you would like to request a free catalog and find out more about The Library of America, please visit with your name and address. Include your e-mail address if you would like to receive our occasional newsletter with items of interest to readers of classic American literature and exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors (we will never share your e-mail address).

Book designed by David Bullen.

Print ISBN: 978-1-59853-109-1

eISBN 978-1-59853-171-8

First eBook Edition: December 2011

:: INTRODUCTION

Describing the Italian film The Night of the Shooting Stars, in 1984, in The New Yorker, Pauline Kael wrote, in words that readers of hers over the years might have used to describe her own reviews, that the movie is so good its thrilling. Kaels movie criticism, with its racing, urgent, crystal clear way of making us see the depth, liveliness, or speciousness of whatever film she was handling, and the funny and uncannily intimate way she got into the skin of actors, or presented miniaturized biographies of directors, or drew out the larger social or ethical implications of a given film, affected readers in precisely that manner. We were given writing replete with so many separate, brilliant awarenesses as to take us, as we absorbed them, to another sphere. The very phrasing Kael used about the Tavianis movieso good its thrillinghas her transformative power. The words are plain and conversational, yet they have been brought together with a blunt assurance that makes us pause and see them anew.

When she stepped down from writing movie reviews at The New Yorker, in 1991, at seventy-two, Kaels retirement was a national news story. For the little over two decades that she had been at the magazine she was undoubtedly the most fervently read American critic of any art. But her renown was based on far more than her coverage of the films of the 1970s and 1980s. In a 1977 review of Steven Spielbergs Close Encounters of the Third Kind, she wrote that Spielberg is a magician in the age of movies, and perhaps more deeply than any other writer Kael gave shape to the idea of an age of movies. In a career that began in the mid-1950s and was fully underway by the early 1960s, she explored movies as an art, an industry, and a sociological phenomenon. A romantic and a visionary, she believed that movies could feed our imaginations in intimate and immediateand liberating, even subversiveways that literature and plays and other arts could not. But she also understood the financial realities and artistic compromises behind moviemaking, and she described them with a specificity and a pertinacity that few other critics did. As concerned with audience reactions as with her own, she could be caught up in how movies stoke our fantasies regardless of their qualities as movies.

She was also, as she wrote, lucky in her timing. Her tenure as a regularly reviewing critic coincided with the modern flowering of movies, the period, primarily the 1960s (for foreign films) and the 1970s (for American films), when moviemakers were working more than ever with the autonomy associated with poets, novelists, and painters. While hardly always laudatory (and to some readers plain wrongheaded), she nonetheless, in the earlier decade, gave a breathing, textured life to the aims and sensibilities of Ingmar Bergman, Jean-Luc Godard, Federico Fellini, Satyajit Ray, Akira Kurosawa, Franois Truffaut, and Michelangelo Antonioni, among other European and Asian directors; and she endowed Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese, Paul Mazursky, Brian De Palma, and Francis Ford Coppola, among American directors of the following decade, with the same full-bodied presence.

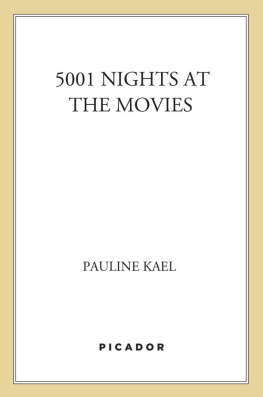

Kaels grasp of film history was encyclopedic. She had seen silent films as a child, in the 1920s, sometimes taking them in on her parents laps. Speaking for her generation, she could thus write of motion pictures that We were in almost at the beginning, when something new was added to human experience; and in her full-length reviews and essays (put together over the years in eleven volumes), and her short notices on films (collected in the mammoth 5001 Nights at the Movies), she encompassed much of that something new. (Her literal output can be gauged by noting that Kael described her 1994 For Keeps, an over 1,200-page selection of what she thought was her best writing, as representing about a fifth of her complete work.)

She had few occasions to write about silent films; but she kept them a living part of her universe by maintaining, for instance, that D. W. Griffiths Intolerance was perhaps the greatest movie ever made and that Maria Falconetti gave possibly the finest performance ever recorded on film in Carl Dreyers The Passion of Joan of Arc. Her views on individual American, European, and Asian movies of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s also exist somewhat in the background of her work as she wrote about them mainly in compressed reviews. But these highly factual and irresistibly readable reviews, which appear in 5001 Nights alongside entries on movies made up through the 1980s, provide for countless films what feel like both perfect introductions and last words.

What gives Kael a distinctive place in American writing, however, has as much to do with what movies prompt in her as it does with her capturing so much of the breadth and lore of movies. Following through on her conviction that movies release us from our normal emotional and social guardedness, she built her criticism, whether her subject is an epochal masterpiece or a tinny Hollywood product, on her most spontaneous and sensory reactions. In a body of work that as a result sometimes has the impact of a single long, indirect, and utterly original kind of autobiography, she immerses us in a flow of dazzlingly stated, unpredictable, sometimes needling and exhortatory, and always humanly large and forthright perceptions. Speaking with the insights of simultaneously a drama coach, a club comedian, a social agitator, a connoisseur, and a psychotherapist, she illuminates the ways that artists of any kind succeed or fail. When she shows how movies can excite, demean, frighten, or stretch us, she makes it seem as if she were talking about the power and capacities of art no matter what its form. Her deepest subject, in the end, almost isnt movies at allit is how to live more intensely.

Next page