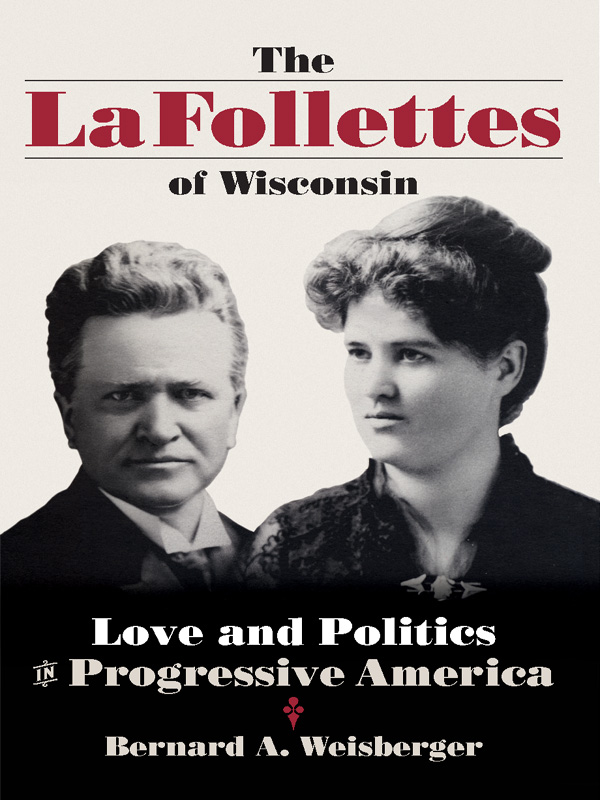

The La Follettes of Wisconsin

LOVE AND POLITICS IN

PROGRESSIVE AMERICA

Bernard A. Weisberger

The University of Wisconsin Press

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 1994 by Bernard A. Weisberger

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

All photographs are courtesy of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. The negative numbers are as follows: , WHi(X3)14473.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weisberger, Bernard A., 1922

The La Follettes of Wisconsin: love and politics

in progressive America / Bernard A. Weisberger.

384 p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-299-14130-6 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. La Follette family. 2. La Follette, Robert M. (Robert Marion), 18551925.

3. La Follette, Belle Case, 18591931. 4. Progressivism (United States politics).

5. United StatesPolitics and government18651933.

6. United StatesPolitics and government19331945. I. Title.

E747.W3 1994

973.90922dc20

[B] 93-32286

ISBN 978-0-299-14134-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-14133-2 (e-book)

For all our grandchildren

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

I remember when I first became an admirer of Robert M. La Follette, Sr. It was 1937. I was fifteen years old and deep in Walter Milliss Road to War, a chronicle of how the United States got involved in what was then the one and only world war. I was strongly influenced by antiwar novels, memoirs, movies, and plays like A Farewell to Arms, All Quiet on the Western Front, and many others. I thought that the war itself was a cruel and meaningless slaughter and Americas entry a tragedy. (I havent changed my mind about that.) Anger and sadness swept over me when I came to the climax of the book, the rainy April night in 1917 when Woodrow Wilson read his war message to a joint session of Congress amid applause and cheers so furious that even the president later expressed surprise. But one senator did not join the hysteria. He listened in stony silence, arms folded on his chest, chewing guman immovable rock in the raging current. That was La Follette of Wisconsin, a hero if ever I had met one in the pages of a history book.

He seemed to me to belong to a time long gone. Like all youngsters, I made little distinction between things that happened five or fifty or five hundred years before I was born. Im not sure that I even knew in 1937 that although La Follette was dead, one of his two sons, Robert, Jr., was in the United States Senate and the other, Philip, was governor of Wisconsin, thereby creating a one-of-a-kind brother act in American politics. Both were still young men, younger than my father.

Im certain that I did not know that Old Bob, my invincible war resister, had run as an independent presidential candidate in 1924 and gotten just under five million votes out of some twenty-nine million cast. One voter in six had gone for him, and that was only thirteen years earlier, very recent history. It might as well have been an official secret for all our school-books had to say about it, and I had not encountered the 1924 election in any of my outside reading on current events. Americas capacity to forget losers is legendary.

Not for another ten years did La Follette re-enter my awareness and then in a big way. In 1947, as a graduate student in United States history, I learned that he was one of the stars of the Progressive movement that swept the nation in the opening years of the twentieth century. In 1891, a seemingly faithful Republican, he had suddenly discovered that Wisconsin was tainted with corruption. For the next nine years he went up and down the rural byways of the state, rallying the people to join him in breaking the unholy alliance between greedy corporations and political bosses, to take back their government. He did not simply harangue listeners. He held them spellbound for hours with avalanches of facts. He told them in precise detail and hard numbers how they were being overtaxed, overcharged, and sold out, how nominating conventions were rigged, how judges were fixed and legislators bribed. He began with most of the money and respectability in the state against him, but in 1900 he won the first of three two-year terms as governor.

He gave Wisconsin a model administration, according to his lights. He pushed bills through the legislature that provided for open primary elections and fair taxation, safeguarded natural resources from land-grabbers and exploiters, and created commissions to regulate banks, insurance companies, utilities, and railroads. To these he appointed independent experts, many of them professors at the state university. He believed they would set competitive rules and rates that would bring the benefits of economic growth to the whole public instead of selected stockholders and insiders. He did not invent all of these ideas, or realize them without other peoples help. They were part of the culture of reform that forward-looking, educated, modern men and women were beginning to share in every big city. But the fires he kindled were visible to national progressive journalists a long way off. They called his state a laboratory of democracy. They popularized the term the Wisconsin Idea to describe his mixture of government by popular will and trained, disinterested intelligence.

La Follette became a national figure. Wisconsin sent him to the Senate in 1905, where he had less power but a bigger stage, and he went on battling, usually in the minority, against the monopolists and their allies in Congress to the end of his days. He made no deals and gave no quarter. He was already known as Fighting Bob when he threw himself in the path of the stampede to war. Only someone of absolute political fearlessness could have done it, and it cost him dearly for a time. But he came back for that last 1924 crusade as the presidential candidate of workers, farmers, and consumers who chose not to vote for Calvin Coolidge, corporate Americas front man, or the Democrat John W. Davis, a conservative lawyer whose economic views were indistinguishable from Coolidges. The next year, weary and aged far beyond his seventy years, Old Bob died of heart failure. Young Bob, barely thirty, was chosen to fill his vacant seat. In 1930 Phil, just thirty-two, captured the Wisconsin statehouse.

The boys carried on the tradition in their fashion. During the thirties Robert, Jr., became best known in the Senate for his chairmanship of an investigating committee that revealed how employers planted thugs and spies in the workplace to break unions. Phil, as a Depression-era governor, was largely preoccupied with public works and relief measures, but he also fought hard for conservation, public power, and tight control of banks and holding companies. Both were first elected as Republicans but in political reality became supporters of the New Deal. Still, they had no love for the Democrats or for Franklin D. Roosevelt, so in 1934 they bolted and ran on the ticket of a newly created Progressive Party of Wisconsin.