This new edition, like previous works, uses the text of the late Arlie Slabaugh. A native of Springfield, Pa., Slabaugh began collecting in 1938 at 16 and grew to become not only an avid collector but a renowned numismatist and author. Slabaughs career included the publication of his own hobby magazine, The Hobby Spotlite, as well as a stint at the Franklin Mint. Slabaugh generously shared his vast knowledge with the numismatic public by writing for publications such as The Numismatic Scrapbook, The Numismatist, Numismatic News and Bank Note Reporter. His work and involvement earned him many awards and honors, including the American Numismatic Associations Lifetime Achievement Award, Numismatic Ambassador Award, and the Numismatic Literary Guilds Clemy Award.

Slabaugh began compiling his catalog of Confederate currency in 1957, with the first edition published in 1958. By the10th edition, published in 2000, no Confederate paper money book had been through as many editions. Sadly, after a long and storied career, Slabaugh passed away in September 2007 in Springfield, during the production of the 11th edition of the catalog.

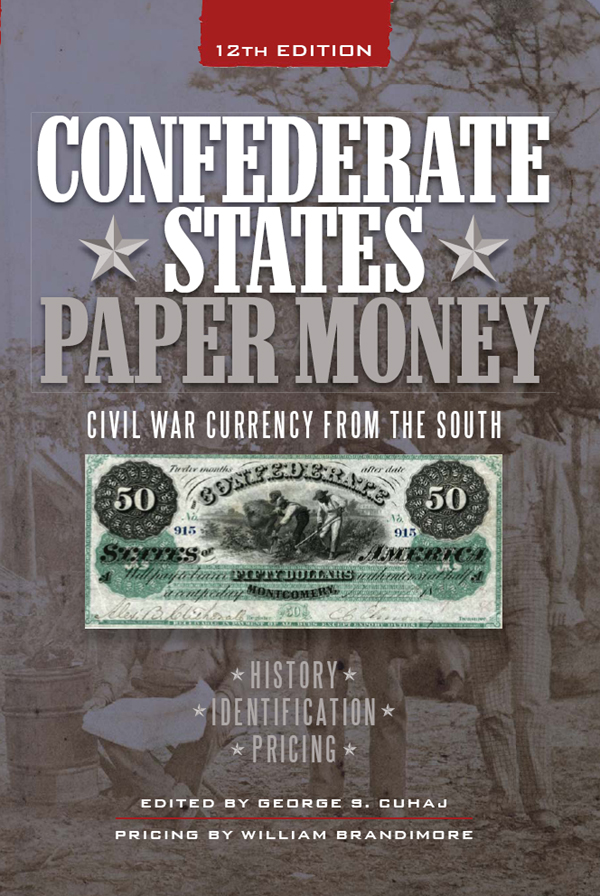

This 12th edition preserves and extends the color images introduced in the 11th edition, but returns to the immensely popular Slabaugh numbering system, at the behest of our readers. Krause Publications is honored and proud to continue to bring Arlie Slabaughs work to our readers.

INTRODUCTION FROM THE 10TH EDITION

by Arlie R. Slabaugh

I began to collect seriously early in 1938 on a planned basis, not just Confederate currency, but many other things. Of particular value at that time was the publication of The Standard Paper Money Catalogue by Wayte Raymond in 1940, which provided me with a list of types so that I knew what to seek. I also learned about the notes from articles published in Raymonds Coin Collectors Journal to which I subscribed, as well as purchasing the 1915-1919 years of The Numismatist, which contained H.D. Allens series of articles on the background of Confederate currency (later included in a 1945 reprint of Bradbeers catalog). By 1946, I had a rather good collection of types as well as some varieties that appealed to me. I was able to assemble all of the types with one exception the Indian Princess note (No. 14) and I could have obtained it, too, but at that time none was offered for sale in better than good condition and I was seeking a better example. (This is still largely true, although higher prices have since attracted better examples to the market.)

The purchase I remember best is that of the $500 Montgomery note (No. 3) that I obtained in XF condition at Kosoffs New York auction in 1942, at what was then said to be a record price of $88. At that time, Raymond catalogued it at $75. Since that note now brings $10,000 or more in similar condition, you can see what unbelievable changes have occurred in the past 50 years. I wish I still had this note, but I sold my original collection many years ago when prices were yet low. In other words, prices listed in this catalog are unbiased, having been obtained from various sources and are not for my personal benefit.

Believing that the approaching Civil War centennial would reawaken interest in Confederate currency (which was not an appreciably active series in the 1950s), I began compiling a catalog 1957, which was published the following year by the Whitman Publishing Co., Racine, Wis. Two further editions (1959 and the 1963 Centennial Edition) were similarly distributed by this company, well-known publishers of the Guide Book of United States Coins. The first edition relied on prices that had been current among dealers up to that time. This was to change as both demand and prices rose due to the increased demand for Civil War artifacts during the Civil War centennial. Nevertheless, prices were still restrained compared to those experienced in the 1990s.

Now that the 10th edition of this catalog has appeared, it may be a good time to review the publication of previous editions. As noted, the first three editions were published by Whitman. The fourth edition appeared in 1967 and was published jointly by me and Hewitt Brothers, Chicago, as a part of its Numismatic Information Series. The same holds true for the fifth edition in 1973 and the sixth edition in 1977. Probably not many collectors own a complete set, but each edition contains price changes or data not in others. The seventh (1991), 8th (1993), 9th (1998) and the 10th edition have been published by Krause Publications, Iola, Wis. No other Confederate paper money catalog has gone through as many editions.

A peculiarity of collecting involves swings in collector interest, whether it be baseball cards, coins, paper money or other subjects. One year, everyone is seeking certain collectibles while a year later the same series may be dead. During the 1990s, interest in paper money of most kinds, not just Confederate, increased greatly, with accompanying increases in prices. Whether future prices will continue to rise, stabilize or drop is unknown, but collectors should be aware of this and collect what they really want to own and not for speculative purposes.

It should be noted, though, that as online auctions and sales via computer continue to grow, the market for Confederate currency may soon exceed its present levels. Should that happen, one is warned that as prices increase, so does the increased likelihood of fakes and modern reproductions being sold as genuine notes that are claimed to be inherited.

A NATION ASUNDER

With the secession of South Carolina on December 20, 1860, the Union, one and inseparable, was a Union no longer. The igniting spark was the question of slavery but the North and the South one industrial, the other agrarian had been drawing apart in many ways since Colonial times.

By February 1861, six Southern states (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia and Louisiana) had seceded from the Union. Delegates from each of these states assembled at the provisional capital in Montgomery, Ala., where a committee of 12 under the chairmanship of Christopher G. Memminger drafted a constitution. Although the Confederacy had its share of radicals, they were overruled by cooler heads and the resulting constitution that was submitted in March to the state governments for approval (but not to public vote), resembled, to a large extent, the U.S. Constitution on which it was based.

Prior to its approval, the Confederate Congress passed an Act on February 9, 1861 that stated, Be it enacted by the Confederate States of America in Congress assembled, that all the laws of the United States of America in force and in use in the Confederate States of America on the 1st day of November last, and not inconsistent with the Constitution of the Confederate States, be, and the same are hereby, continued in force until altered or repealed by the Congress. After all, not only had Southerners lived for many years under U.S. laws, many of the delegates had served in the state houses or the U.S. Congress and were familiar with the U.S. Constitution. It was not like they were inexperienced men preparing the document from scratch. Rather, they were trying to improve the U.S. Constitution to meet the needs of the South.