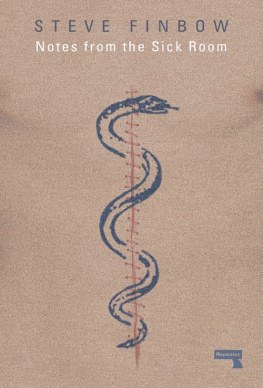

Finbow - Notes from the Sick Room

Here you can read online Finbow - Notes from the Sick Room full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2017;2016, publisher: Watkins Media;Repeater Books, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Notes from the Sick Room: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Notes from the Sick Room" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Notes from the Sick Room — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Notes from the Sick Room" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

NOTES FROM THE SICK ROOM

Steve Finbow

Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

19-21 Cecil Court

London

WC2N 4EZ

UK

www.repeaterbooks.com

ARepeaterBooks paperback original 2017

Copyright Steve Finbow 2017

Steve Finbow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover design: Johnny Bull

Typography and typesetting: JCS Publishing Service Ltd

Typefaces: Minion Pro and Gill Sans

ISBN: 978-1-910924-97-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-910924-43-3

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Contents

Sickness was what restored me to reason.

Friedrich Nietzsche Ecce Homo

The doctor will see you now. If you follow me, we can commence the tour of the hospital, but first a short induction. The title Notes from the Sick Room stems from three sources: Life in the Sick-Room: Essays by an Invalid (1844), by the social theorist Harriet Martineau, a treatise and memoir on chronic suffering; Notes from Sick Rooms (1883), a healthcare manual written by Julia Princep Stephen, Virginia Woolf s mother; and Death in the Sick Room (1885), a painting by Edvard Munch, now in the Munch Museum, Oslo. Artists, writers and theorists are the source of this investigation how they deal with illness and injury and how they work through and within their affliction or, indeed, cease to create because of the physical and psychological trauma.

The evaluation will be of physical complaints: broken bones, cancer, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and any attendant problems; it will not cover mental illnesses apart from when these are secondary symptoms of the main condition. There are excellent studies on creativity and mental illness (or the Sylvia Plath effect, as it has become known), but not many on physical illness and the problems of creating while living with disability. Of course, a change in the physical wellbeing of an artist may induce forms of mental illness, but the primary goal of this examination is the effects of trauma on an artist and the subsequent effects on their work and life.

On our journey through the hospital and the sanatorium that stands within its gardens we will meet some of the patients: Christopher Hitchens and Kathy Acker in the cancer ward; Frida Kahlo and Denton Welch in the orthopaedic department; Bruce Chatwin and Michel Foucault in the HIV/AIDS unit; and, John Keats, the Bronts, Robert Louis Stevenson, Katherine Mansfield and D.H. Lawrence et alia, when we take a tour of the tuberculosis sanatorium. Along the way, we will also encounter Bob Dylan, Roland Barthes, Andy Warhol, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Roberto Bolao, Fritz Zorn, Frigyes Karinthy and many others in a time-travelling compound from which we will distil their thoughts and creations within and through their disorders.

Helping us with our ward rounds will be specialists, resident theorists who will either concur with our diagnosis or provide a second opinion. These consultants include: Roland Barthes (when hes not in a hospital bed), Michel Foucault (likewise), Anton Chekhov (doctor, patient, writer), J.G. Ballard, Georges Bataille, E.M. Cioran, Jean-Luc Nancy, Gilles Deleuze, Flix Guattari, Oliver Sacks and a host of other interns, medical officers, registrars and heads of department. Susan Sontag, who is on sabbatical, will join us for the conclusion of the disquisition. The overriding theory derives from our chief physician, Dr Friedrich Nietzsche, whose health and illness informed his life and work and whose The Gay Science (1882) (more recently translated as The Joyous Wisdom) is the manual we will be turning to as a guide to our probings and proddings.

And here is Dr Nietzsches abstract for the book from his own Preface to the second edition (1886) of The Gay Science: A psychologist knows few questions as attractive as that concerning the relation between health and philosophy; and should he himself become ill, he will bring all of his scientific curiosity into the illness. For assuming that one is a person, one necessarily also has the philosophy of that person; but here there is a considerable difference. In some, it is their weaknesses that philosophize; in others, their riches and strengths. The former need their philosophy, be it as a prop, a sedative, medicine, redemption, elevation, or self-alienation; for the latter, it is only a beautiful luxury, in the best case the voluptuousness of a triumphant gratitude that eventually has to inscribe itself in cosmic capital letters on the heaven of concepts. In the former, more common case, however, when it is distress that philosophizes, as in all sick thinkers and perhaps sick thinkers are in the majority in the history of philosophy what will become of the thought that is itself subjected to the pressure of illness?

We will examine the patients case notes, their medical history and lifestyles, question them on symptoms and pain management, and hope to form a diagnosis of the correlation, or otherwise, between illness and creativity. The primary source material will be their letters, journals, memoirs and the biographical data written about them. We will also study the fiction and non-fiction produced by writers, songs and pieces written by musicians and artworks created by artists.

There will be a brief introductory chapter on the hospital and its creation and the emergence of medicine as a separate science through the works of Hippocrates, Empedocles and other Classical scholars, plus a study of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, plus other non-Western founders of medicine and its studies. Throughout the text, so as not to appear aloof and indifferent, we will also scrutinize my own medical history and how it relates (or otherwise) to the bed-ridden writers and artists within the hospital. The germ of this study began when I was recuperating in Chitose City Hospital, Hokkaido, Japan, after complications from a norovirus illness, and had lapsed into a coma over the 2006 Christmas period (of which more later). On regaining consciousness, I realized that I had nearly missed the deadline to enter the Willesden Short Story Competition. I asked my partner to print out and bring in the short story, it still needed editing and I had one day to get it finished. It was six-thousand words long and I wanted to get it down to under four-thousand. My throat was full of exudative pharyngitis, white clumps of bacteria or fungus surrounded my pharynx, probably caused by the doctors who saved my life. My taste buds were shot tea tasted like Bovril, the mackerel in tomato sauce the nurses brought me for breakfast suggested Battenberg cake, the miso soup accompanying it was more like Lucozade. I was on an intravenous drip for my electrolytes and an insulin pump because of my type-one diabetes (the cause of my coma). I took the pages of Mrs. Nakamoto Takes a Vacation and went at the text with a red pen, an inky scalpel with which I excised the tumorous material and resected the mass. Because of the deadline, I worked quickly, but this was also because of my fatigue and my focus. If I had been healthy and at home, I would have dithered, read a book, gone for a walk, played on the Wii, maybe even added five hundred words to the story, thought it was good enough. But in the hospital room I looked at the words and saw the text needed excoriating, the skin needed to be taken off so all that was left was its muscle and bone structure. The first paragraph eventually read: She fixes herself a bowl of miso soup, steamed rice, and pickled plums and takes them on a tray into the living room to eat while watching the weather report on television. The day is going to be warm a thin layer of cloud burning off by midday. Mrs. Nakamoto nods, finishes the last drops of her soup, fills a bottle with water and leaves the house. The journey to the station takes fifteen minutes and she walks in her usual manner small steps, head slightly bowed, turning her neck left and right and dipping her forehead as a greeting to people she knows, people she sees most mornings. The people do the same. Nothing is said, just the incline of the head and the muffled grunt of acknowledgement. But she doesnt recognize anyone this morning. Where is the man with the excitable dogs? Where are the schoolchildren eating persimmons? Where is the old man with the red umbrella? For me that is concise, and it is so because of the concentration of thought(s) while recovering from a diabetic coma in the strange environment of a Japanese hospital.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Notes from the Sick Room»

Look at similar books to Notes from the Sick Room. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Notes from the Sick Room and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.