Ford - The Architectural Detail

Here you can read online Ford - The Architectural Detail full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2011;2012, publisher: Princeton Architectural Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Architectural Detail: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Architectural Detail" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Architectural Detail is author Edward R. Fords lifes work, and this may be his most important book to date. Ford walks the reader through five widely accepted (and wildly different) definitions of detail, in an attemptto find, once and for all, the quintessential definition of detail in architecture.

Ford: author's other books

Who wrote The Architectural Detail? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Architectural Detail — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Architectural Detail" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Architectural Detail

The

Architectural

Detail

Edward R. Ford

Princeton Architectural Press, New York

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East Seventh Street

style="margin-bottom:20px;">New York, New York 10003

For a free catalog of books, call 1-800-722-6657

Visit our website at www.papress.com.

2011 Princeton Architectural Press

All rights reserved

14 13 12 11 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Carolyn Deuschle

Designer: Jan Haux

Special thanks to: Bree Anne Apperley, Sara Bader, Janet Behning, Nicola Bednarek Brower, Fannie Bushin, Megan Carey, Carina Cha, Tom Cho, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Russell Fernandez, Felipe Hoyos, Linda Lee, Jennifer Lippert, Gina Morrow, John Myers, Katharine Myers, Margaret Rogalski, Dan Simon, Andrew Stepanian, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ford, Edward R.

The architectural detail / Edward R. Ford. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56898-978-5

ISBN 978-1-61689-160-2 (digital)

1. ArchitectureDetails. I. Title.

NA2840.F66 2011

721dc22

2010018460

To Jane

Preface

No construction, no architecture.

Julien Gaudet

When I wrote the following pages, or rather when I began them, I lived in a third-floor flat overlooking the green at Cambridge Universitys Downing College. It was a familiar landscape, much like the Lawn of the University of Virginia, my own school. The Lawn was begun nineteen years after the founding of Downing in 1800, and there are remarkable similarities between the two landscapes: both have central greens; both greens are flanked by ranges with pavilions, and both have a large central building closing one end. There are also significant differences. William Wilkins Downing is Greek Revival in form and built of Ketton stone, whereasThomas Jeffersons Virginia is more Palladian-influenced and built of brick and wood. Virginias central building was its library; its chapel, a post-Jeffersonian afterthought built in 1890, sits uncomfortably to one side. In perfect asymmetry with Virginia, Downings chapel lies on the central axis, while its library occupies the periphery. It is an afterthought as well, having been built in 1993. Like Downing, Virginia continues to expand its historic core, having just completed a library for special collections at the periphery of its lawn, and thus both institutions faced the question of how to build adjacent to the context of an architectural unity that is separated from the present not only by 180 years but also by a significant technological, and to many ideological, gap. Both institutions have answered this question in the same way: their overriding objective is to imitate their stylistic context, whether Federal Style or Greek Revival architecture.

Shortly after my return to Virginia, with a number of other faculty, I coauthored an open letter to the universitys administration and community at large, deploring the historicist prison in which the university had placed itself, arguing that Jeffersons architectural legacy was not one of literal symbols, but rather of a set of larger principles. In the letter we asked, rhetorically, that this policy of glib, shallow revivalism be at the very least reexamined. The process of writing the letter revealed some odd truths about its authors. We were united in our criticism of the status quo, but our individual reasoning was diverse and, at times, contradictory. Some were troubled by the lack of authenticity of the campuss new buildings, by the pseudohistorical implications of revivalism. Some were troubled by the issue of diversity, by the Eurocentric and historical associations of universal classicism. Some sought a more sensitive response to the landscape. Some were troubled by attitudes toward preservation, by the universitys policy of destruction of real histories and construction of fictitious ones. Many said it was not about style at all, arguing that better site planning, greater variety, and simply better buildings would solve the problem.

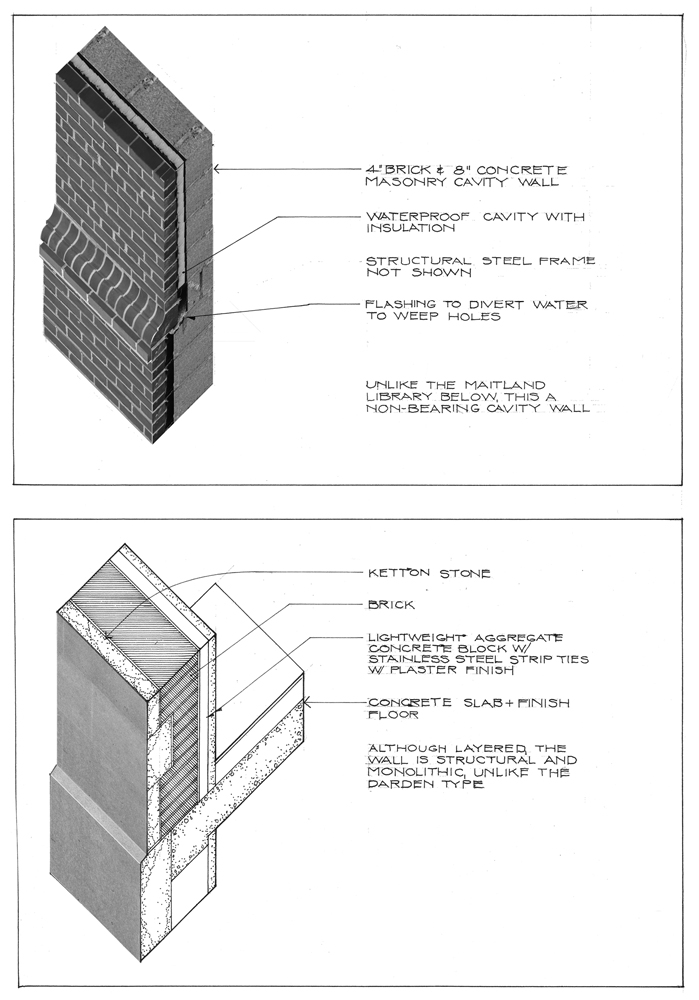

Given that the bulk of my teaching career has been spent in the subject of construction, it might be assumed that my own objection to the new buildings at the University of Virginia was that they have failed to bridge the gap between their late-eighteenth-century imagery and the modern technology that it conceals. The solid brick wall has become a veneer; the arches, once a structural necessity, are now supported by steel; the small pane of glass has become large. Yet the imagery remains, full of false headers, quoins, muntins, steel-supported lintels, and precast classical columns. Few things are more visually painful than these buildings in their incomplete state: steel-framed structures with concrete block infill awaiting their 4-inch veneer of Colonial architecture. Virginias new library is built this way, and so are the great majority of its historicist counterparts.

But this paradoxical construction is not the inevitable choice for this kind of revivalist architecture. There are few such tensions between real construction and preconceived imagery in the new Downing library. The walls are solida layer of four-inch Ketton stone bonded to eight-inch brick, with insulation provided by an inner layer of three-inch insulating block. They are structural and, except for the roof, there is no concealed steel frame.

fig. 1

Top

Wall Detail, Darden School of Business, University of Virginia, Robert A.M. Stern, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1996

Bottom

Wall Detail, Maitland Robinson Library, Downing College, Quinlan Terry, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1993

Does this solve the problem posed by the new Virginia library? In a way, yes, but constructional solidity was, to me, not enough. The Downing library, however well made, has no ambitions beyond vague historical allusions. This is architecture by association, and an architecture based solely on historical association can only be a glib, disingenuous, and transient one, however ancient its references or solid its construction. Good architecture has a deeper structure, in the largest sense of the word.

Ultimately my problem with the new libraries at Downing and Virginia was not that either is a building in which the technology of one historical period is clad in the language of another, not that either building used literal symbols, not that they were oblivious to the technology of the modern world, not that they were classical per se, not that they recalled repressive societies from the past, not that they were Eurocentric, not that their forms originated in a belief in absolute standards of beauty to which few if any of their admirers subscribe, although all these things were problematic. The problem was their details. It was not that their details delivered a message with which I disagreed. It was not that they were ornaments; it was that in great buildings, the details, in the sense of a demonstration of constructional resolution, are the means of delivering whatever message architecture communicates.

This has no better illustration than the Lawn itself. There was a consensus among the authors of the letter that the meaning of the Lawn lay not in its superficial appearance, but in a body of principles of which it is the manifestation, that is, that there is a deeper structure below the surface that gives the Lawn its significance. Understandably, many readers of the letter objected to the implications of this, arguing that if all articulationcapitals, bases, moldings and trimof the various parts that make up the Lawns architecture disappeared, the result would be a very un-Jeffersonian, unified monolith. To strip the Lawn of its ornaments, they argued, would deprive it of all character and significantly alter its meaning. Proportion, composition, and geometry were insufficient, the argument went, and if the ornaments were removed, one would need to replace them with something else, not necessarily historical, not necessarily even recognizable as a symbol, but something that would perform the tasks of the older ornaments that transcends their historical associations. I agree; some type of detail was necessary. But to find a true detail meant that one had to get beyond the familiar and find what Louis Kahn calls its point of beginning. I am not so naive as to argue that classical ornaments have constructional origins, although many believe this, and some ornaments probably do. But as details, and not as ornament, they perform a variety of tasks beyond historical recollection, and this recollection is an impediment, not an aid, to understanding the larger order of the architecture and its meaning.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Architectural Detail»

Look at similar books to The Architectural Detail. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Architectural Detail and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.