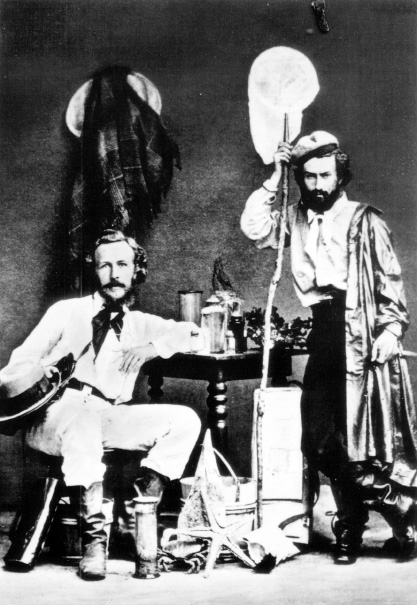

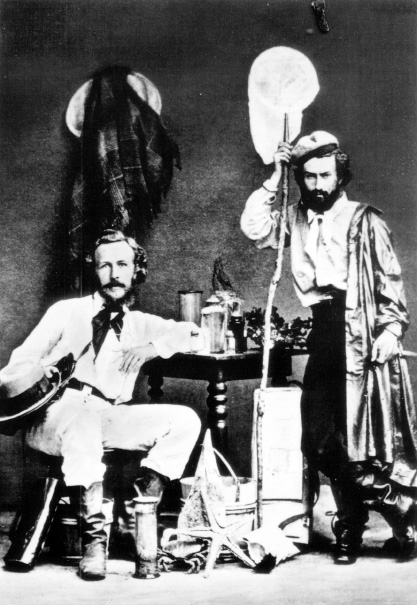

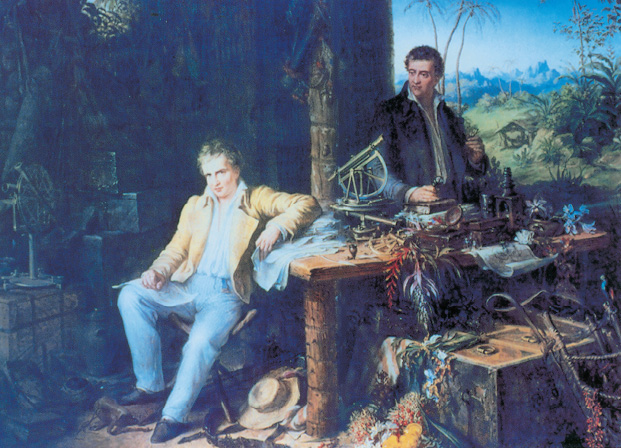

Ernst Haeckel (seated) and his assistant Nikolai Miklucho on the way to the Canary Islands in 1866. Haeckel had just visited Darwin in the village of Downe. (Courtesy of Ernst-Haeckel-Haus, Jena.)

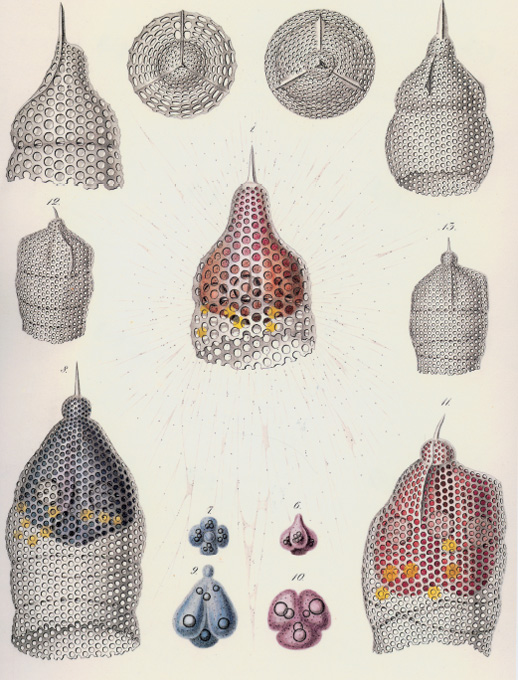

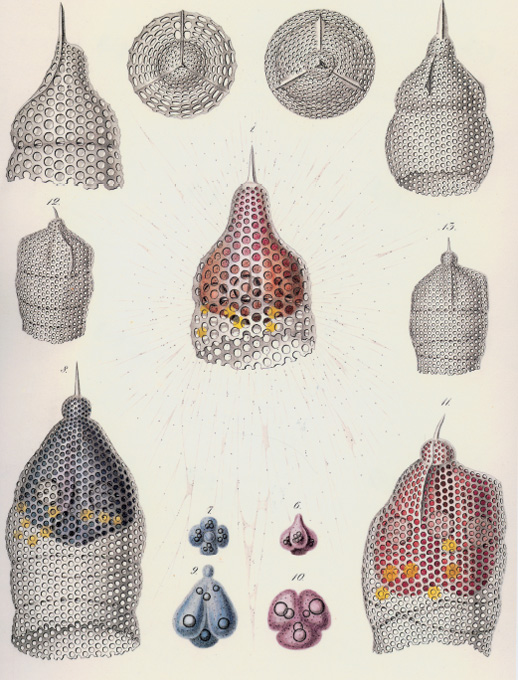

PLATE 1: Radiolaria of the subfamily Eucyrtidium. (From Haeckel, Radiolarien, 1862.)

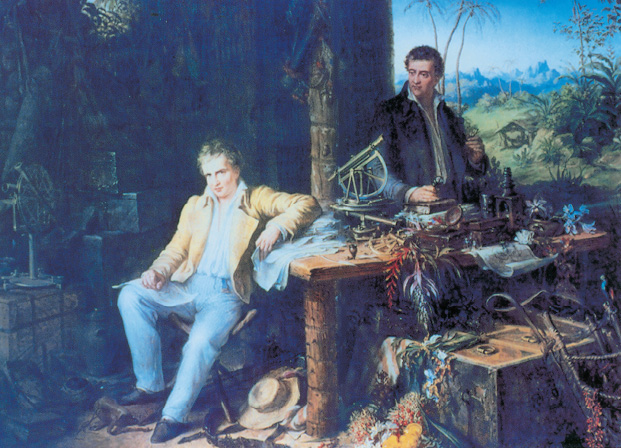

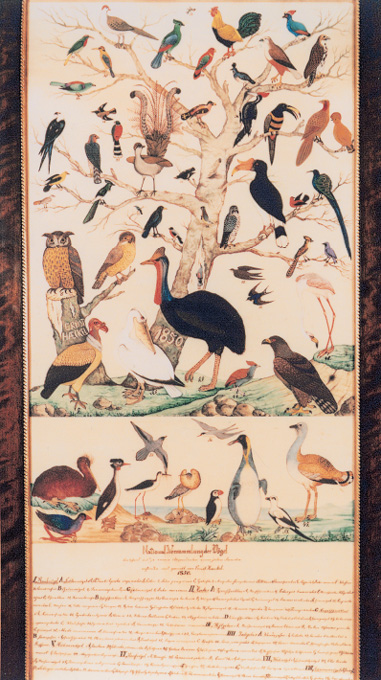

PLATE 2: Alexander von Humboldt and Aim Bonpland in their laboratory by the Orinoco. Oil on canvas (c. 1850) by Eduard Ender. (Courtesy of Archiv fr Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin.)

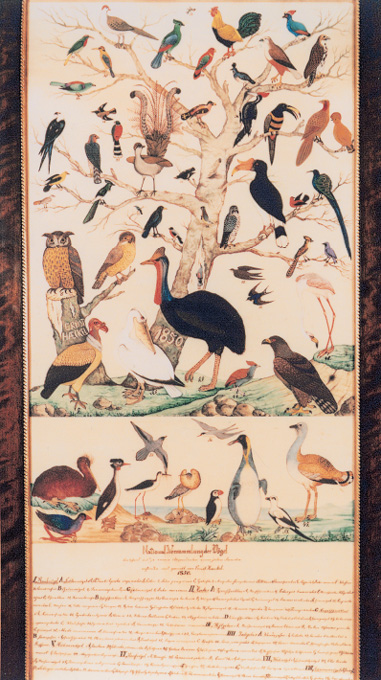

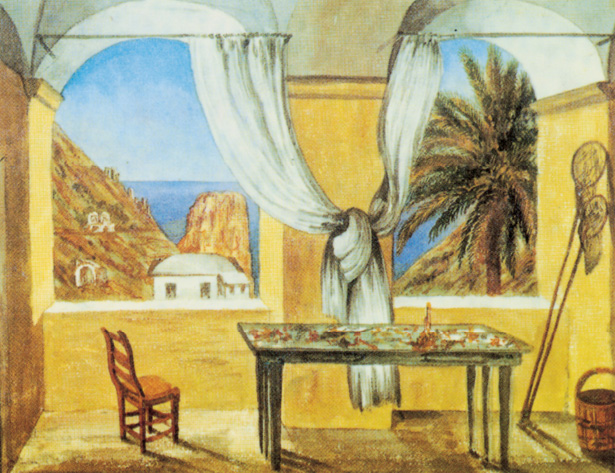

PLATE 3: Haeckels portrait (1850) of the Nationalversammlung der Vgel (Parliament of birds). (Courtesy of Ernst-Haeckel-Haus, Jena.)

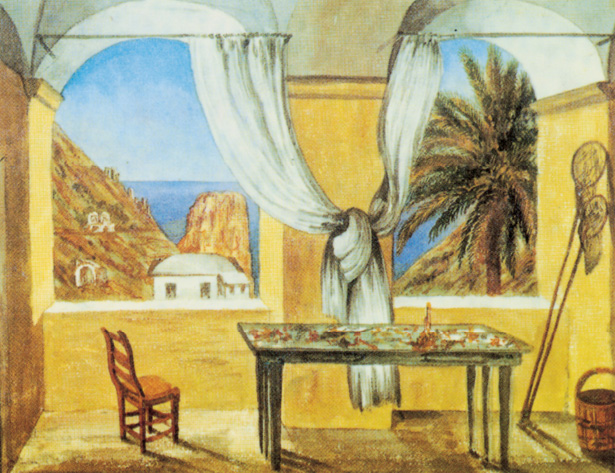

PLATE 4: Haeckels watercolor (1859) of his study on Capri. (Courtesy of Ernst-Haeckel-Haus, Jena.)

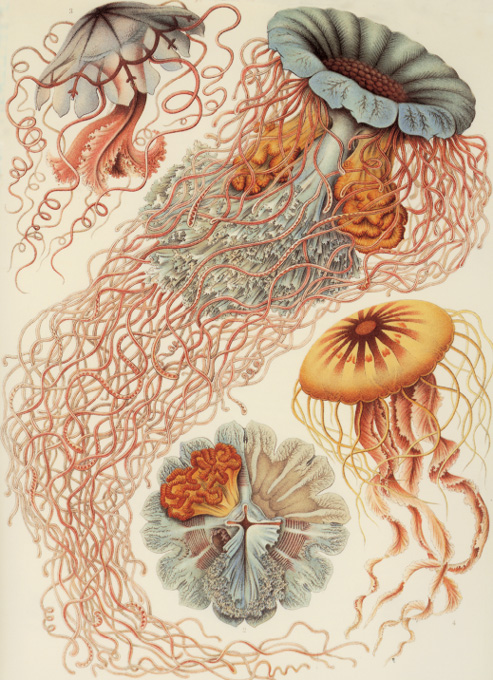

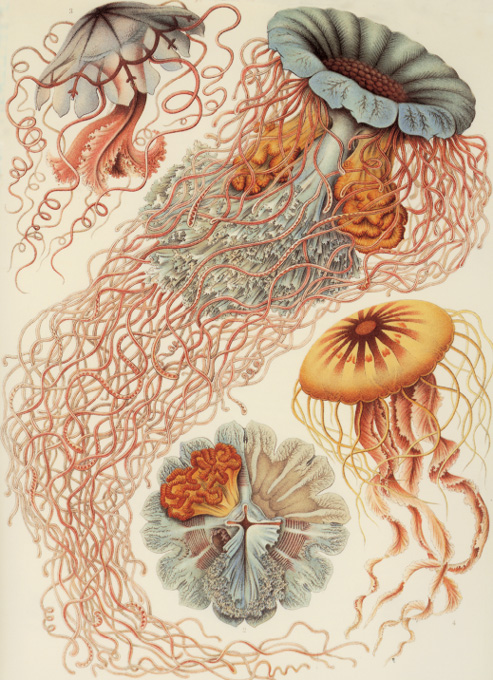

PLATE 5: Discomedusa Desmonema Annasethe. (From Haeckel, System der Medusen, 1879.)

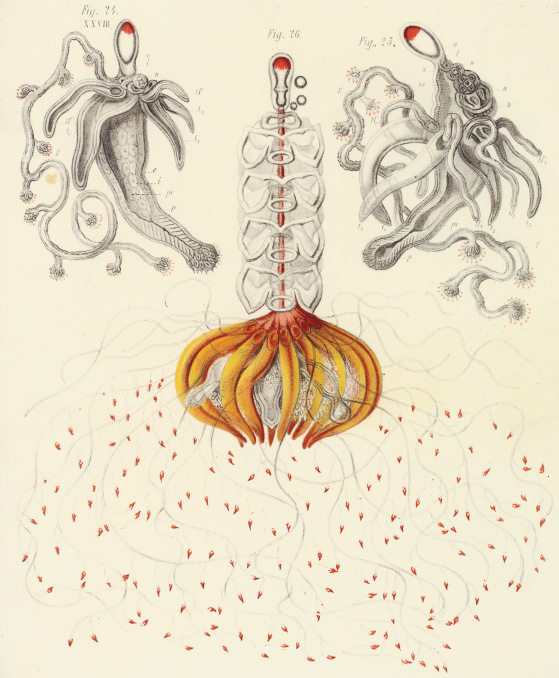

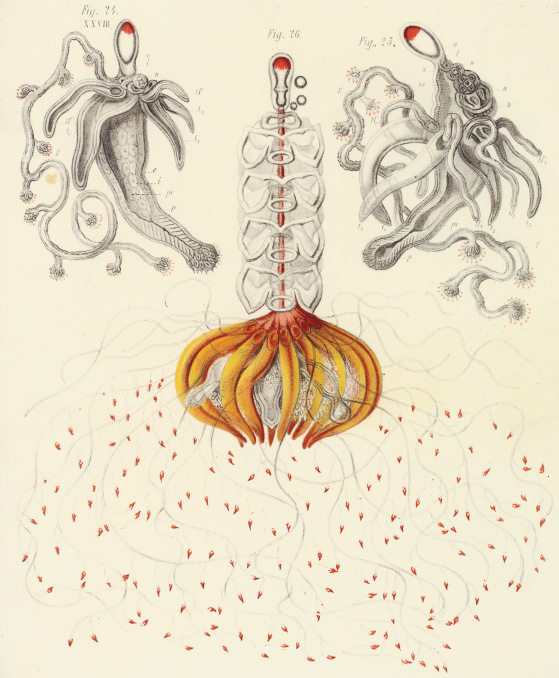

PLATE 6: Physophora magnifica, flanked by two larvae at slightly different stages of development. (From Haeckel, Zur Entwickelungsgeschichte der Siphonophoren, 1869.)

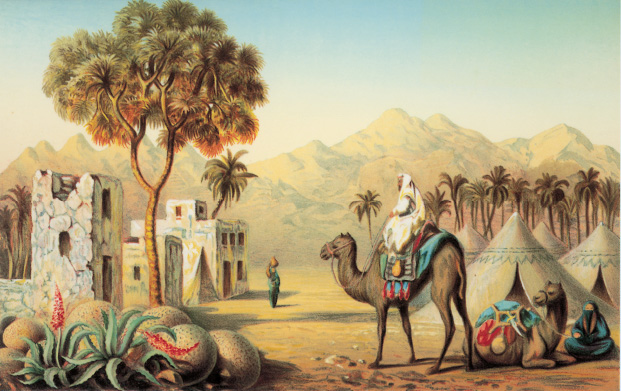

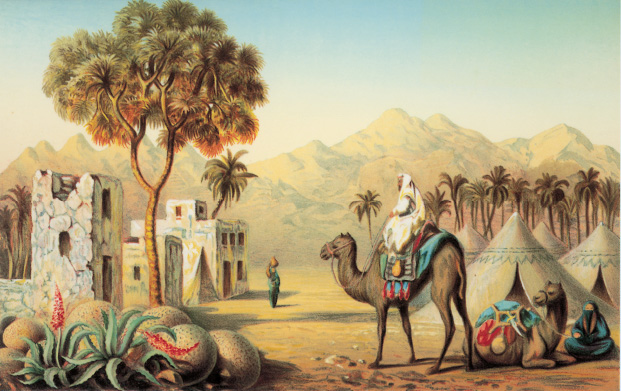

PLATE 7: Scene painted by Haeckel and lithographed for his Arabische Korallen, 1876.

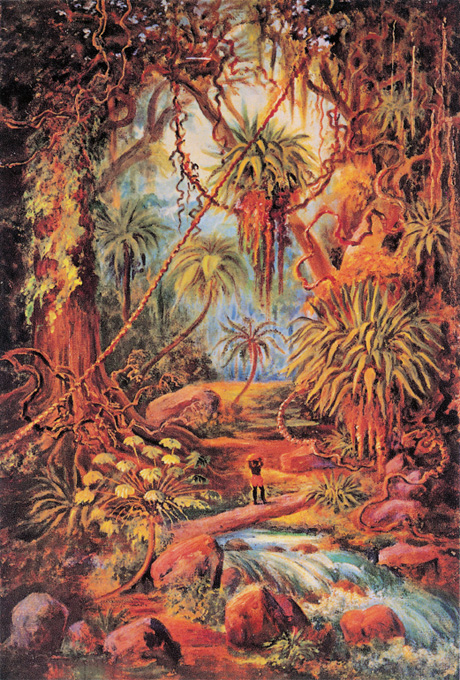

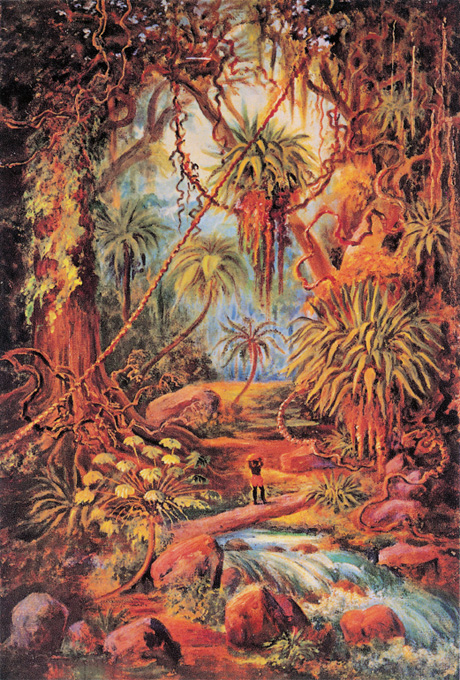

PLATE 8: Highlands of Java; oil landscape by Haeckel. (From Haeckel, Wanderbilder, 1905.)

THE TRAGIC SENSE OF LIFE

Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over Evolutionary Thought

ROBERT J. RICHARDS

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2008 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2008

Paperback edition 2009

Printed in the United States of America

18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 3 4 5 6

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71214-7 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71216-1 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71219-2 (e-book)

ISBN-10: 0-226-71214-1 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-71216-8 (paper)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Richards, Robert J. (Robert John)

The tragic sense of life: Ernst Haeckel and the struggle over evolutionary thought

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71214-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-71214-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Haeckel, Ernst Heinrich Phillipp August, 18341919. 2. BiologistsGermanyBiography. 3. ZoologistsGermanyBiography. 4. Evolution (Biology)History. I. Title.

QH31.H2R53 2008

570.92dc22

[B]

2007039155

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

FOR MY COLLEAGUES AND STUDENTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

ILLUSTRATIONS

, Ernst Haeckel and Nikolai Miklucho

Plates

PREFACE

The nineteenth century was an age of enlightened science and romantic adventure. The age rippled with individuals of outsize talents. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the great German poet-scientist, joined aesthetic considerations with analytical observations to engage in two great scientific pursuits, a recalcitrant study of optics and an innovative construction of morphology. The former foundered on the rocks of his poetic genius, but the latter gave birth to a new discipline that became integral to biology. Alexander von Humboldt, a dashing disciple of Goethe, sailed to the New World in 1799 and spent five years exploring the jungles and social character of South and Central America. The intellectual results of his quest elevated him to the very summit of European science and culture. His travels became the inspiration for that other great romantic adventure, Charles Darwins journey on HMS Beagle. Darwins theory of evolution by natural selection transformed the thought of the period as had no other scientific accomplishment before or since. The last part of the nineteenth century was dominated in theoretical physics and experimental physiology by the polymath Hermann von Helmholtz, an individual who vied with Goethe for cultural hegemony. And at the very end of the century, Sigmund Freud completed his Interpretation of Dreams, which would become an icon of modernist science during the first half of the twentieth century, competing with Einsteins discoveries in broad intellectual significance, if not scientific import.

Another individual of comparable stature in his own time and with a reverberating impact on ours was Ernst Haeckel, Darwins great champion in Germany. His name is not as well known as some of the others I have mentioned, but virtually everyone is aware of the principle he made famous: the biogenetic law that ontogeny recapitulates phylogenythat is, that the embryo of a contemporary species goes through the same morphological changes in its development as its ancestors had in their evolutionary descent. More people at the turn of the century were carried to evolutionary theory on the torrent of his publications than through any other source, including Darwins own writings. He waged war against orthodoxies of every sort and is largely responsible for fomenting the struggle between evolutionary science and religion that still stirs our social and political life. Like Goethe and Humboldt, whom he revered, his science was transported by deep currents of aesthetic inspiration. He was a gifted artist who illustrated all of his own works, making them accessible to a wider audience and a target for conservative opponents. Despite the maelstrom of controversy that engulfed his work, few individuals, except perhaps Darwin and Helmholtz, garnered from contemporaries more notable prizes, honorary degrees, and prestigious accolades. Though today the term genius has been debased and regarded as suspect, if it means startling creativity, tireless industry, and deep artistic talent, it should not be denied to Haeckel. His scientific ideas rebounded on Darwin, especially regarding human evolution. Helmholtz supported him and Freud made recapitulation a central doctrine of psychoanalysis. Casting ones historical vision lower, to the area of his special expertise, marine invertebrate biology, one still finds more creaturesradiolaria, medusae, siphonophores, spongeshaving their species designation bearing his name than that of any other investigator.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.