Murray N. Rothbard - The Ethics of Liberty

Here you can read online Murray N. Rothbard - The Ethics of Liberty full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

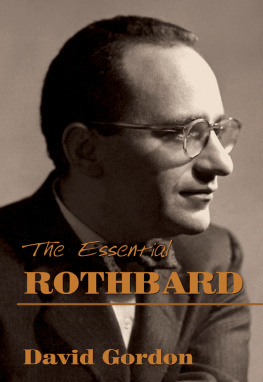

- Book:The Ethics of Liberty

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ethics of Liberty: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Ethics of Liberty" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Ethics of Liberty — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Ethics of Liberty" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

By Hans-Hermann Hoppe

In an age of intellectual hyperspecialization, Murray N. Rothbard was a grand system builder. An economist by profession, Rothbard was the creator of a system of social and political philosophy based on economics and ethics as its cornerstones. For centuries, economics and ethics (political philosophy) had diverged from their common origin into seemingly unrelated intellectual enterprises. Economics was a value-free "positive" science, and ethics (if it was a science at all) was a "normative" science. As a result of this separation, the concept of property had increasingly disappeared from both disciplines. For economists, property sounded too normative, and for political philosophers property smacked of mundane economics. Rothbard's unique contribution is the rediscovery of and philosophy, and the systematic reconstruction and conceptual integration of modern, marginalist economics and natural-law political philosophy into a unified moral science: libertarianism.

Following his revered teacher and mentor, Ludwig von Mises, teachers Eugen von Bhm-Bawerk and Carl Menger, and an intellectual tradition reaching back to the Spanish late-Scholastics and beyond, Rothbardian economics sets out from a simple and undeniable fact and experience (a single indisputable axiom): that man acts, that humans always and invariably pursue their most highly valued ends (goals) with scarce means (goods). Combined with a few empirical assumptions (such as that labor implies disutility), all of economic theory can be deduced from this incontestable starting point, thereby elevating its propositions to the status of apodictic, exact, or a priori true empirical laws and establishing economics as a logic of action (praxeology). Rothbard modeled his first magnum opus, Man, Economy, and State on Mises's monumental Human Action. In it, Rothbard developed the entire body of economic theoryfrom utility theory and the law of marginal utility to monetary theory and the theory of the business cyclealong praxeological lines, subjecting all variants of quantitative-empirical and mathematical economics to critique and logical refutation, and repairing the few remaining inconsistencies in the Misesian system (such as his theory of monopoly prices and of government and governmental security production). Rothbard was the first to present the complete case for a pure-market economy or private-property anarchism as always and necessarily optimizing social utility. In the sequel, Power and Market, Rothbard further developed a typology and analyzed the economic effects of every conceivable form of government interference in markets. In the meantime, Man, Economy, and State (including Power and Market as its third volume) has become a modern classic and ranks with Human Action as one of the towering achievements of the Austrian School of economics.

Ethics, or more specifically political philosophy, is the second pillar of the Rothbardian system, strictly separated from economics, but equally grounded in the nature of man and complementing it to form a unified system of rationalist social philosophy. The Ethics Liberty, originally published in 1982, is Rothbard's second magnum opus. In it, he explains the integration of economics and ethics via the joint concept of property; and based on the concept of property, and in conjunction with a few general empirical (biological and physical) observations or assumptions, Rothbard deduces the corpus of libertarian law, from the law of appropriation to that of contracts and punishment.

Even in the finest works of economics, including Human Action, the concept of property had attracted little attention before Rothbard burst onto the intellectual scene with Man, Economy, and State. Yet, as Rothbard pointed out, such common economic terms as direct and indirect exchange, markets and market prices, as well as aggression, invasion, crime, and fraud, cannot be defined or understood without a prior theory of property. Nor is it possible to establish the familiar economic theorems relating to these phenomena without an implied notion of property and property rights. A definition and theory of property must precede the definition and establishment of all other economic terms and theorems.

At the time when Rothbard had restored the concept of property to its central position within economics, other economistsmost notably Ronald Coase, Harold Demsetz, and Alchianalso began to redirect professional attention to the subject of property and property rights. However, the response and the lessons drawn from the simultaneous rediscovery of the centrality of the idea of property by Rothbard on the one hand, and Coase, and Alchian on the other, were categorically different.

The latter, as well as other members of the influential Chicago School of law and economics, were generally uninterested and unfamiliar with philosophy in general and political philosophy in particular. They unswervingly accepted the reigning positivistic dogma that no such thing as rational ethics is possible. Ethics was not and could not be a science, and economics was and could be a science only if and insofar as it was "positive" economics. Accordingly the rediscovery of the indispensable role of the idea of property for economic analysis could mean only that the term property had to be stripped of all normative connotations attached to it in everyday "non-scientific" discourse. As long as scarcity and hence potential interpersonal conflict exists, every society requires a well-defined set of property rights assignments. But no absoluteuniversally and eternallycorrect and proper or false and improper way of defining or designing a set of property rights exists; and there exists no such thing as absolute rights or absolute crimes, but only alternative systems of property rights assignments describing different activities as right and wrong. Lacking any absolute ethical standards, the choice between alternative systems of property rights assignments will be madeand in cases of interpersonal conflicts should be made by government judgesbased on utilitarian considerations and calculations; that is, property rights will be so assigned or reassigned that the monetary value of the output produced is thereby maximized, and in all cases of conflicting claims government judges should so assign them.

Profoundly interested in and familiar with philosophy and the history of ideas, Rothbard recognized this response from the outset as just another variant of age-old self-contradictory ethical relativism. For in claiming ethical questions to be outside the realm of science and then predicting that property rights will be assigned in accordance with utilitarian benefit considerations or should be so assigned by government judges, one is likewise proposing an ethic. It is the ethic of statism, in one or both of two forms: either it amounts to a defense of the status quo, whatever it is, on the grounds that lastingly existing rules, norms, laws, institutions, etc., must be efficient as otherwise they would already have been abandoned; or it amounts to the proposal that conflicts be resolved and property rights be assigned by state judges according to such utilitarian calculations.

Rothbard did not dispute the fact that property rights are and historically have been assigned in various ways, of course, or that the different ways in which they are assigned and reassigned have distinctly different economic consequences. In fact, his Power and Market is probably the most comprehensive economic analysis of alternative property rights arrangements to be found. Nor did he dispute the possibility or importance of monetary calculation and of evaluating alternative property rights arrangements in terms of money. Indeed, as an outspoken critic of socialism and as a monetary theorist, how could he? What Rothbard objected to was the argumentatively unsubstantiated acceptance, on the part of Coase and the Chicago law-and-economics tradition, of the positivistic dogma concerning the impossibility of a rational ethic (and by implication, their statism) and their unwillingness to even consider the possibility that the concept of property might in fact be an ineradicably normative concept which could provide the conceptual basis for a systematic reintegration of value-free economics and normative ethics.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Ethics of Liberty»

Look at similar books to The Ethics of Liberty. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Ethics of Liberty and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.