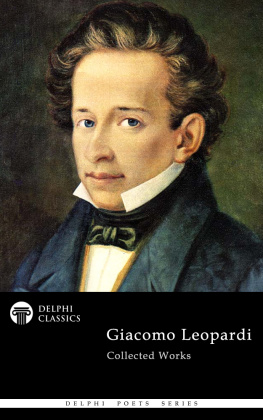

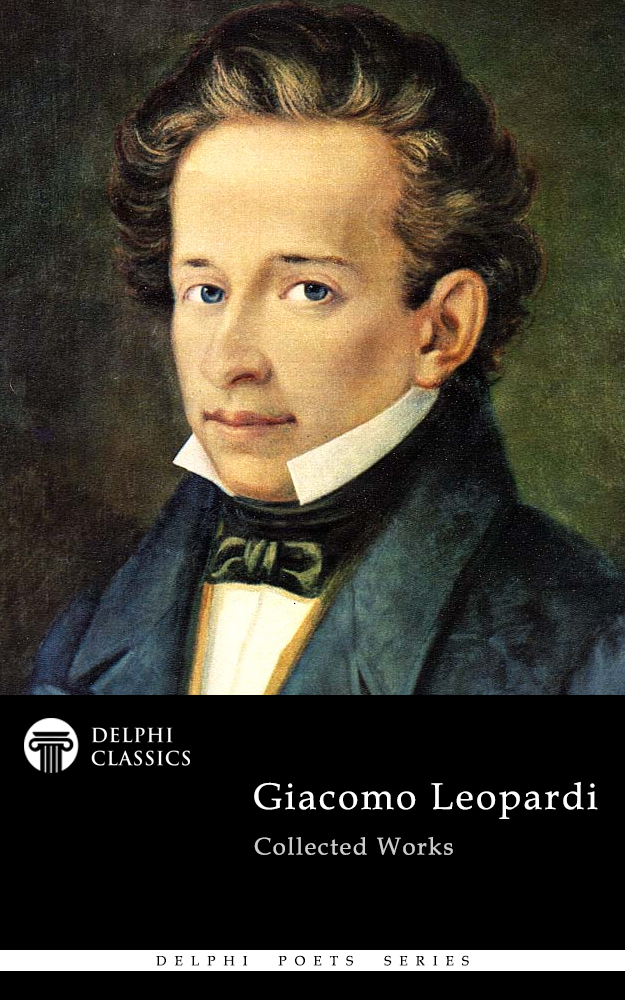

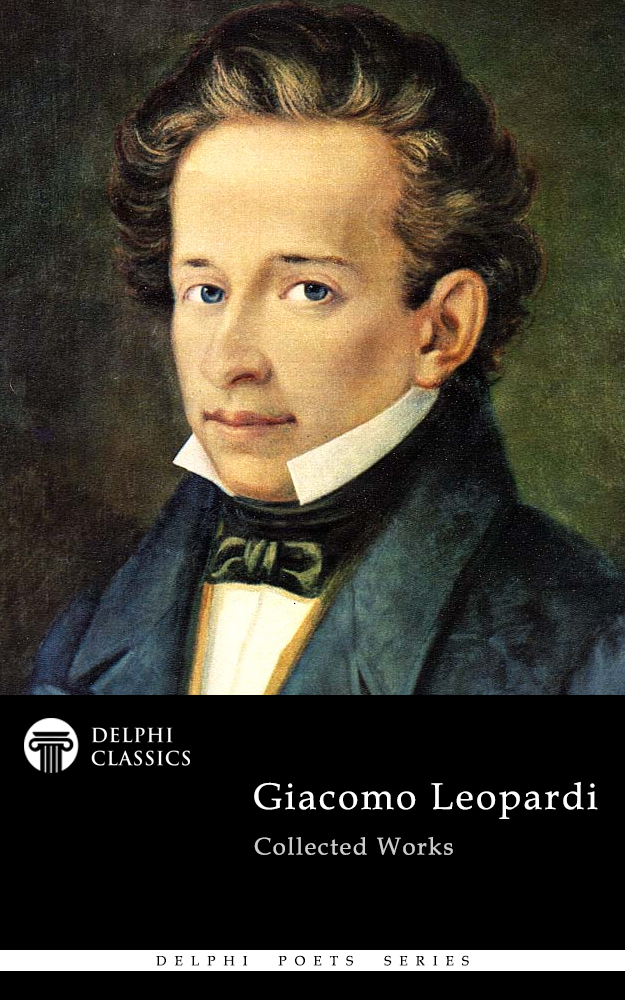

Giacomo Leopardi

(1798-1837)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2019

Version 1

Browse the entire series

Giacomo Leopardi

By Delphi Classics, 2019

COPYRIGHT

Giacomo Leopardi - Delphi Poets Series

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2019.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78877 957 9

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

NOTE

When reading poetry on an eReader, it is advisable to use a small font size and landscape mode, which will allow the lines of poetry to display correctly.

The Life and Poetry of Giacomo Leopardi

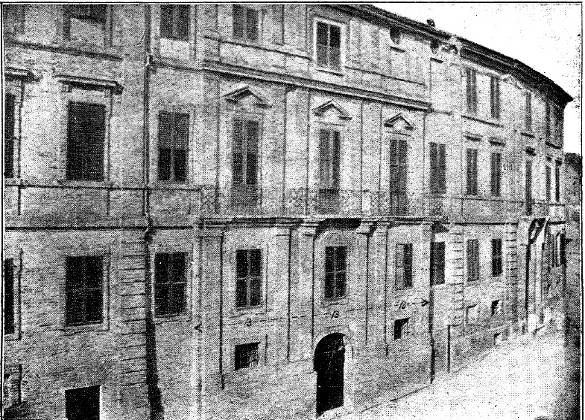

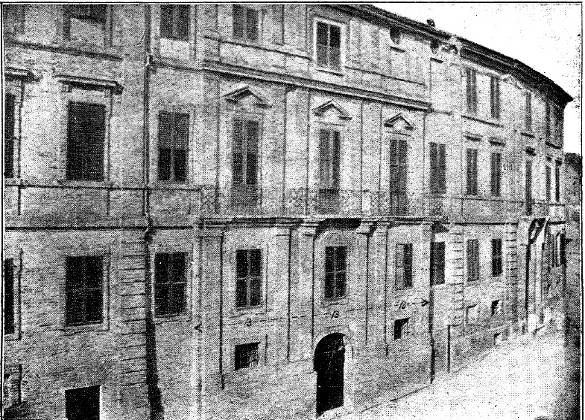

Recanati, a town in the Marche region of central Italy Leopardis birthplace

The birthplace in 1889

The birthplace today

Brief Introduction: Giacomo Leopardi by William Dean Howells

From Modern Italian Poets; Essays and Versions

I N THE YEAR 1798, at Recanati, a little mountain town of Tuscany, was born, noble and miserable, the poet Giacomo Leopardi, who began even in childhood to suffer the malice of that strange conspiracy of ills which consumed him. His constitution was very fragile, and it early felt the effect of the passionate ardor with which the sickly boy dedicated his life to literature. From the first he seems to have had little or no direction in his own studies, and hardly any instruction. He literally lived among his books, rarely leaving his own room except to pass into his fathers library; his research and erudition were marvelous, and at the age of sixteen he presented his father a Latin translation and comment on Plotinus, of which Sainte-Beuve said that one who had studied Plotinus his whole life could find something useful in this work of a boy. At that age Leopardi already knew all Greek and Latin literature; he knew French, Spanish, and English; he knew Hebrew, and disputed in that tongue with the rabbis of Ancona.

The poets father was Count Monaldo Leopardi, who had written little books of a religious and political character; the religion very bigoted, the politics very reactionary. His library was the largest anywhere in that region, but he seems not to have learned wisdom in it; and, though otherwise a blameless man, he used his son, who grew to manhood differing from him in all his opinions, with a rigor that was scarcely less than cruel. He was bitterly opposed to what was called progress, to religious and civil liberty; he was devoted to what was called order, which meant merely the existing order of things, the divinely appointed prince, the infallible priest. He had a mediaeval taste, and he made his palace at Recanati as much like a feudal castle as he could, with all sorts of baronial bric--brac. An armed vassal at his gate was out of the question, but at the door of his own chamber stood an effigy in rusty armor, bearing a tarnished halberd. He abhorred the fashions of our century, and wore those of an earlier epoch; his wife, who shared his prejudices and opinions, fantastically appareled herself to look like the portrait of some gentlewoman of as remote a date. Halls hung in damask, vast mirrors in carven frames, and stately furniture of antique form attested throughout the palace the splendor of a race which, if its fortunes had somewhat declined, still knew how to maintain its ancient state.

In this home passed the youth and early manhood of a poet who no sooner began to think for himself than he began to think things most discordant with his fathers principles and ideas. He believed in neither the religion nor the politics of his race; he cherished with the desire of literary achievement that vague faith in humanity, in freedom, in the future, against which the Count Monaldo had so sternly set his face; he chafed under the restraints of his fathers authority, and longed for some escape into the world. The Italians sometimes write of Leopardis unhappiness with passionate condemnation of his father; but neither was Count Monaldos part an enviable one, and it was certainly not at this period that he had all the wrong in his differences with his son. Nevertheless, it is pathetic to read how the heartsick, frail, ambitious boy, when he found some article in a newspaper that greatly pleased him, would write to the author and ask his friendship. When these journalists, who were possibly not always the wisest publicists of their time, so far responded to the young scholars advances as to give him their personal acquaintance as well as their friendship, the old count received them with a courteous tolerance, which had no kindness in it for their progressive ideas. He lived in dread of his sons becoming involved in some of the many plots then hatching against order and religion, and he repressed with all his strength Leopardis revolutionary tendencies, which must always have been mere matters of sentiment, and not deserving of great rigor.

Next page