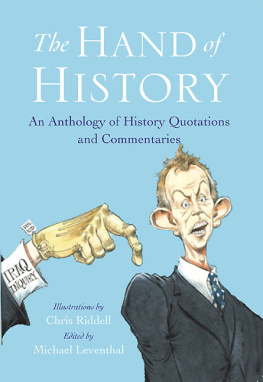

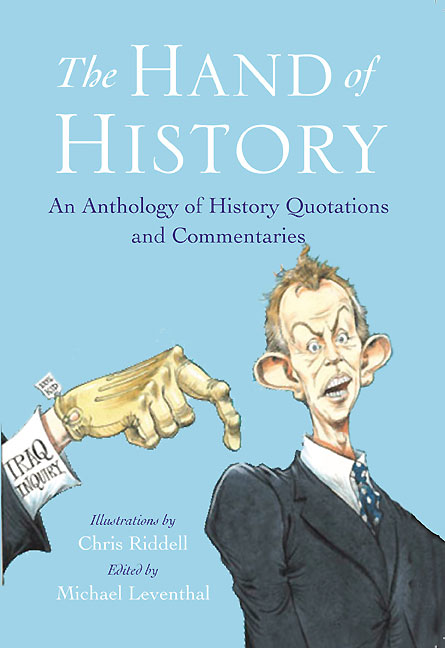

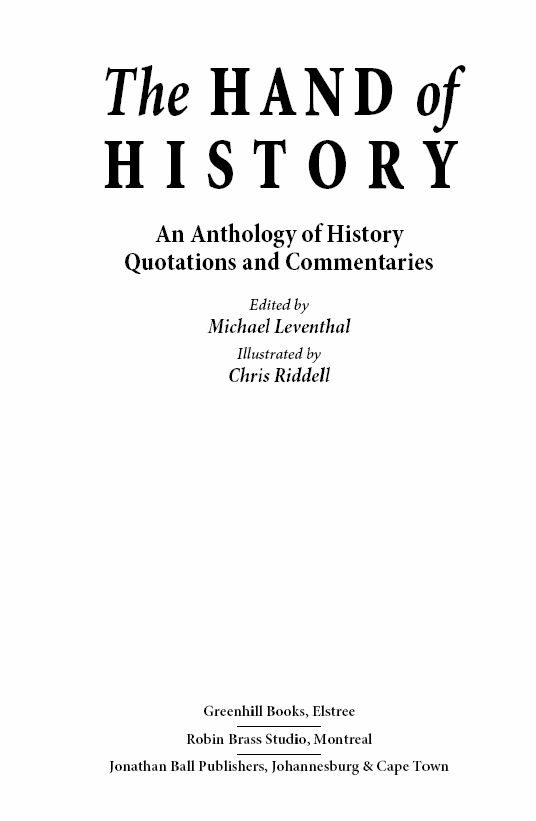

The Hand of History

This edition published in 2011 by Greenhill Books, 3 Barham Avenue, Elstree, Herts, WD6 3PW www.greenhillbooks.com

Greenhill Books are distributed by Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

Published in Canada in 2011 by Robin Brass Studio Inc. www.rbstudiobooks.com

Copyright Michael Leventhal, 2011

All royalties from this book are being donated to support research into Parkinsons disease.

The right of the Contributors to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-623-1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication The hand of history : an anthology of quotes and commentaries / edited by Michael Leventhal ; drawings by Chris Riddell.

Includes bibliographical references.

Co-published by: Greenhill Books.

ISBN 978-1-84832-623-1

eISBN 9781848326682

1. World history Quotations, maxims, etc.

I. Leventhal, Michael E. J.

D20.H35 2011 909 C2011-903721-1

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Mackays, Chatham

Typeset in 9.5/11.5 point Minion Pro

Introduction

The title for this book was taken from Tony Blairs remark on the eve of Northern Irelands Good Friday Agreement. On 8 April 1998, the then prime minister declared, A day like today is not a day for soundbites, we can leave those at home. But I feel the hand of history upon our shoulder I really do. In an era renowned in Britain for political spin, the leader of the Labour Party professed to disparage soundbites and yet in the same breath he delivered the most memorable one of his career.

Blairs comment seems an apt starting-point: aside from being a wonderful piece of irony it provides a typical example of how history is authoritatively invoked by world leaders. The resolution of a relatively small matter is pronounced historic to inflate the importance of the event and usually the ego of the leader too. History is presented as an omniscient authority that provides a true reckoning normally one that chimes with the speaker's version of events.

For centuries, politicians and commentators have employed historical precedents to justify political and military strategies. But history can easily be abused; besides simple falsification a selective use of historical facts can be equally misleading. When intellectuals and politicians from nascent or would-be states speak of constructing a national identity or a national history it invariably entails a parade of partisan facts to support a particular narrative. That said, all history is necessarily selective. Moreover, people have varying perceptions of the history they share. Those differences are often the source of misunderstanding and conflict.

My aim in preparing this anthology was to delve into some of these issues. A number of leading historians were invited either to write an aphorism about history or to select a quote about history or its writing. They were also asked to provide a short commentary explaining their choice. More than one hundred historians worldwide responded and the result is a remarkable roll-call of the most respected writers on history today. I worried that their commentaries might be repetitious. Far from it. A welcome aspect of this collection is the diversity of their responses.

One theme that has emerged is the changing role of the individual in the writing of history. This tallies with my experience as a reader and a publisher: in recent decades there has been an increasing emphasis on both the role of the ordinary individual and also the details of their lives. It is what might be termed the personalization of history. Arguably it has come at the expense of grand sweeping narratives in all schools of history.

Traditional Marxist histories have concentrated on movements of impersonal power and underlying forces rather than particular individuals. But then, in 1963, E. P. Thompson published his seminal social history, The Making of the English Working Class . Thompson announced his intention to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the obsolete hand-loom weaver from the enormous condescension of posterity.

A similar, significant point for military readers my own discipline was John Keegans Face of Battle , published more than a decade later in 1976. The author explicitly stated that his intention was to move from the grandiose canvases of military history and to focus instead on the minutiae of individual lives. And Keegan was right: people like to read about people.

Neither Keegan nor Thompson was simply pandering to the market but they both appreciated that readers had started to want life injected into high politics and strategy. They want to understand how people and not just kings and commanders ate, slept, danced and died. In this context, the success of Max Arthur's recent Voices series compilations of twentieth-century personal accounts is not surprising: eyewitness testimonies can provide the most vivid, basic and emotive picture of individual lives in the past.

This personalisation is one reason that history, particularly narrative history, now appeals to much wider audiences; Peter Furtado, for ten years the editor of History Today magazine, suggested to me that the sale of history books is greater than ever because the story has been put back into history.

This significant change has coincided with and has partly been a product of the general democratization of Western society from the 1960s and 1970s. With the erosion of class barriers and a decline of deference to authority, readers have expected more equality in the subjects of history.

I was recently fortunate to publish Secret Days , the Bletchley Park account of Asa Briggs. Lord Briggs, ninety this year, described his journey from economic historian in the 1940s, to social historian, cultural historian, and finally human historian with the publication of his wartime experiences, in which he was writing as both an historian and a former participant. He conceded that his personal development may have been the result of a disdain for the institutionalization of sub-histories but it also reflects his reactions to the changes that have taken place in the writing of history during the past seventy years.

These developments may be a consequence of the growth in the range of media in which history can be presented. History is more accessible than ever before; it appears in prime-time documentaries on television every night and it can be found online at all times. And thanks to the internet anyone with a pinch of curiosity can conduct their own researches into their genealogy or any aspect of history in almost any language. Access to materials online did not engender the rise of interest in family history but it has made such investigations easier and more appealing.