This compelling book deftly integrates issues of gender, age, history, and politics in its bold reevaluation of the Shakespeare canon. Vanhouttes argument insightfully qualifies, and sometimes overturns, new historicist paradigms of Elizabethan sexualityboth generally and literally defined.

Douglas Bruster, Mody C. Boatright Regents Professor of American and English Literature, Distinguished Teaching Professor at the University of Texas at Austin

In this stunning appraisal of sexual senescence in Shakespeares plays, Jacqueline Vanhoutte shines a light on a figure whos been hiding in plain sight: the aging male lover. Far from risible rous, characters such as Falstaff and Antony embody the politically potent but sexually quiescent men who hovered around Elizabeth in her final years. Beautifully written and hugely original, Age in Love pulls off that rarest of acts: adding a dimension to the highly defined profiles of some of Shakespeares best-known characters.

Paul Menzer, professor and director of the Shakespeare and Performance graduate program at Mary Baldwin University

In clear and elegant prose this book builds a persuasive case for Shakespeares plays as deeply engaged with court history. Exposing the limits of New Historicist analysis, [it] offers a brilliant and groundbreaking methodology for producing historically informed literary analysis.

Catherine Loomis, author of The Death of Elizabeth I: Remembering and Reconstructing the Virgin Queen

Early Modern Cultural Studies

Series Editors

Carole Levin

Marguerite A. Tassi

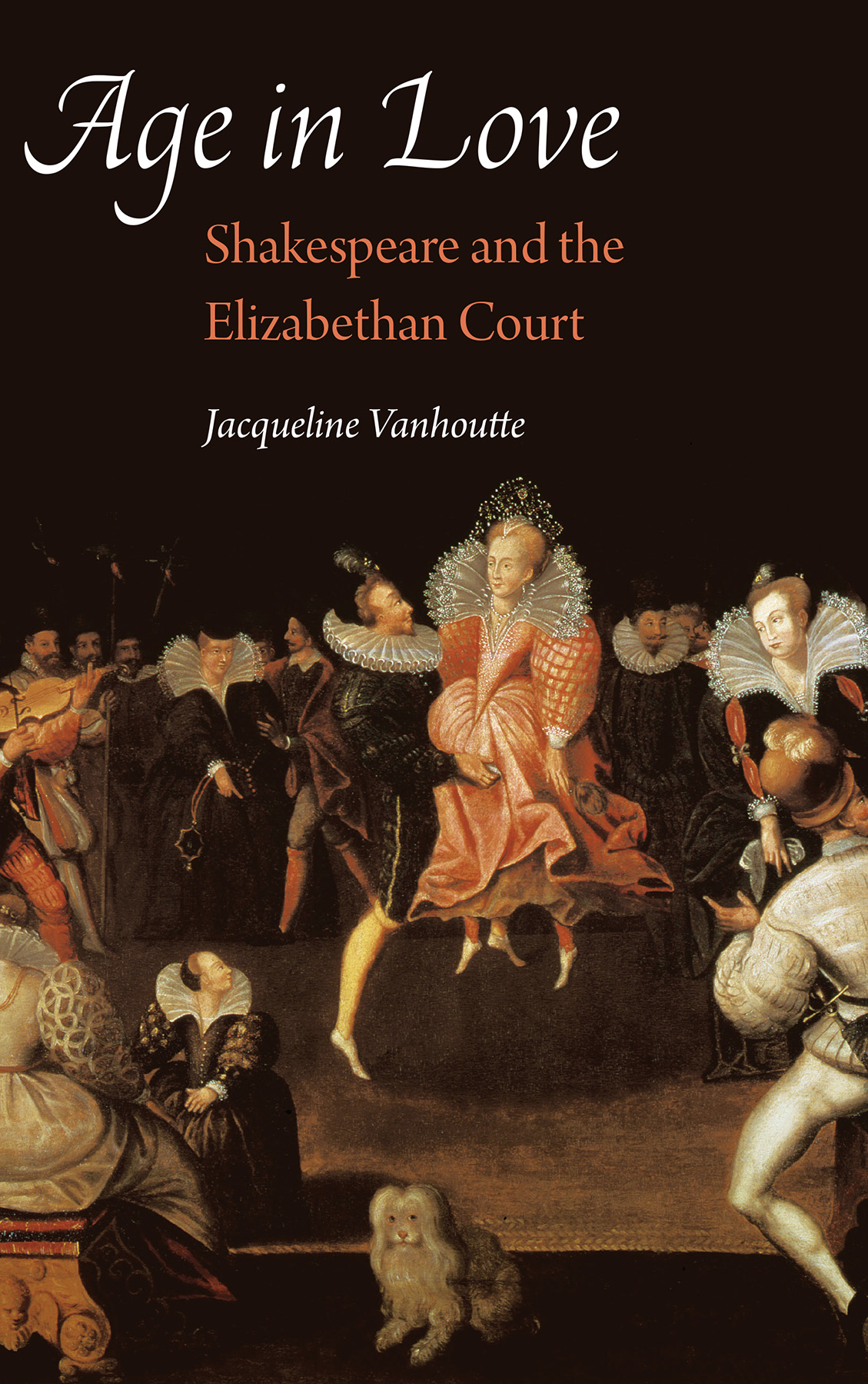

Age in Love

Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Court

Jacqueline Vanhoutte

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

2019 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

A short version of chapter 1 appeared in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 37 (2011): 5170. An early draft of chapter 2 appeared in English Literary Renaissance 43.1 (2013): 86127 ( 2013 by English Literary Renaissance Inc.). Thanks to these journals for their permission to reuse these materials.

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image Elizabeth I Dancing the Volta / akg-images.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Vanhoutte, Jacqueline, 1968 author.

Title: Age in love: Shakespeare and the Elizabethan court / Jacqueline Vanhoutte.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019. | Series: Early modern cultural studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018051867

ISBN 9781496207593 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496214539 (epub)

ISBN 9781496214546 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496214553 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Shakespeare, William, 15641616Political and social views. | Shakespeare, William, 15641616CharactersQueens. | Elizabeth I, Queen of England, 15331603Relations with courts and courtiers. | English literatureEarly modern, 15001700History and criticism. | Older men in literature. | Courts and courtiers in literature. | Great BritainCourt and courtiersHistory16th century.

Classification: LCC PR 3024 . V 36 2019 | DDC 822.3/3dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018051867.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To the memory of my beloved grandmother, Emma Dethier Vandenberghe (19142009). I have seen some majesty and I know it.

Contents

This book would not have been possible without the unfailing support and intellectual generosity of my husband, Alex Pettit. His confidence in my work sustains me when my own flags. Marrying him is the best career choice I made. Im deeply grateful as well to John Coldewey, who introduced me to the joys of early drama and who passed away as I was finishing the manuscript. After all this time, I still write for him, my kind, witty, charming, and exacting first reader. My daughter Claire, who is fourteen, patiently put up with this book for the majority of her life. She brought me joy and much-needed relief. Carole Levin has been a model, a mentor, and an inspiration for my entire career. Her trailblazing scholarship paved the way for so many women in the field, including myself. I have also benefited greatly from Catherine Loomiss learned comments, her wise counsel, and her vast knowledge of the period. I am grateful to Marguerite Tassi, Jo Carney Eldridge, and Alisa Plant for their faith in the book, and to the anonymous reviewers who have contributed important insights over the years. My chairs, David Holdeman and Robert Upchurch, encouraged and funded my research, as did others at the University of North Texas. Amanda Kellogg, Heidi Cephus, and Christa Reaves assisted me at various stages. Thanks are due as well to my friend and colleague Jeff Doty, with whom I discuss my ideas about Renaissance drama at length. Faith Lipori, Corey Marks, Amy Taylor, Nicole Smith, and Paul and Jacqueline Vanhoutte provided crucial emotional support. Miranda Wilson gave me important feedback and thirty-seven years of friendshipfor this, much thanks. Paul Menzer and Doug Bruster kindly lent their support at the end. My work reflects conversations with numerous other friends, students, and colleagues, including the members of the Elizabeth I Society and the attendees of the Blackfriars Convention in Staunton. Thanks also to the two long-eared souls who spanieled me at the heels throughout the writing process, Emma and Cleopatra.

I take the title of this book from Shakespeares Sonnet 138, a poem about an aging male speaker who, by virtue of his sexual entanglement with the dark lady, vainly performs the role of some untutord youth (138.25).

Although the gap in age between the sonnet speaker and his love objects is of obsessive concern in the sequence, coloring almost every motive and action in the relationships to which the Sonnets refer, critics have been This silence is all the more striking given that Shakespeares decision to embrace the perspective of a lover whose days are past the best (138.6) is not an aberration. Rather, we might think about the poetic persona of the sonnets as a kind of signature, an overt admission on Shakespeares part of his enduring fascination with the amorous experiences of older men. The pattern that I am calling age in love pervades Shakespeares mature works, informing his experiments in all dramatic genres. Many of his most memorable charactersBottom, Othello, Claudius, Falstaff, and Antony, to name a fewshare with the sonnet speaker a tendency to flout generational decorum by assuming the role of the young gallant (Merry Wives of Windsor, 2.1.22). These superannuated lovers supplement their role-playing through costume changes: Bottom takes on an asss head, Malvolio dons his stockings and garters, Falstaff and Antony dress like women. Hybrids and upstarts, cross-dressers and shape-shifters, comic butts and tragic heroes, Shakespeares old men in love turn in boundary-blurring performances that probe the multiple categories by which early modern subjects conceived of identity. The ways in which these protean characters draw attention not just to gender distinctions (as do the androgynous heroines of the romantic comedies) but also to generic and generational ones make them flexible vehicles for a range of social, political, philosophical, and aesthetic inquiries. In the chapters that follow, I show that questions that we have come to regard as quintessentially Shakespeareanabout the limits of social mobility, the nature of political authority, the transformative powers of the theater, the vagaries of human memory, or the possibility of secular immortalityreceive indelible expression through his artful deployment of the age-in-love trope.

Next page