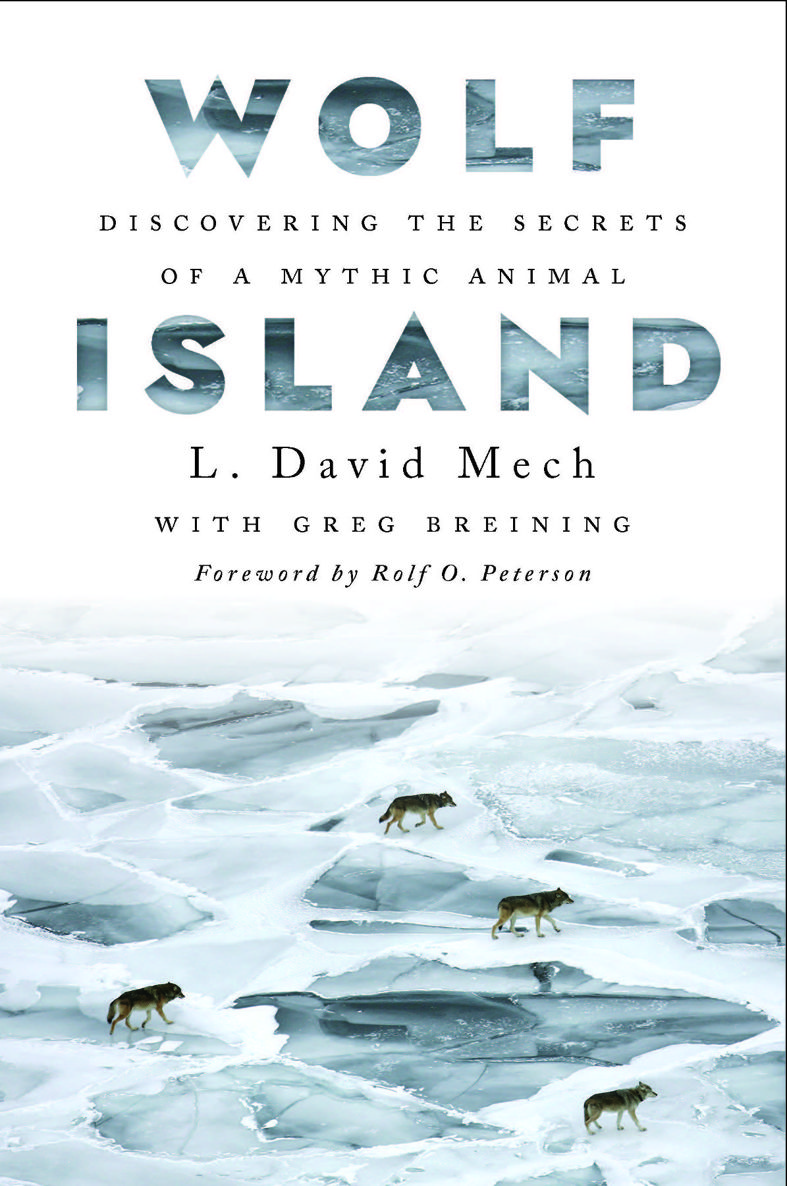

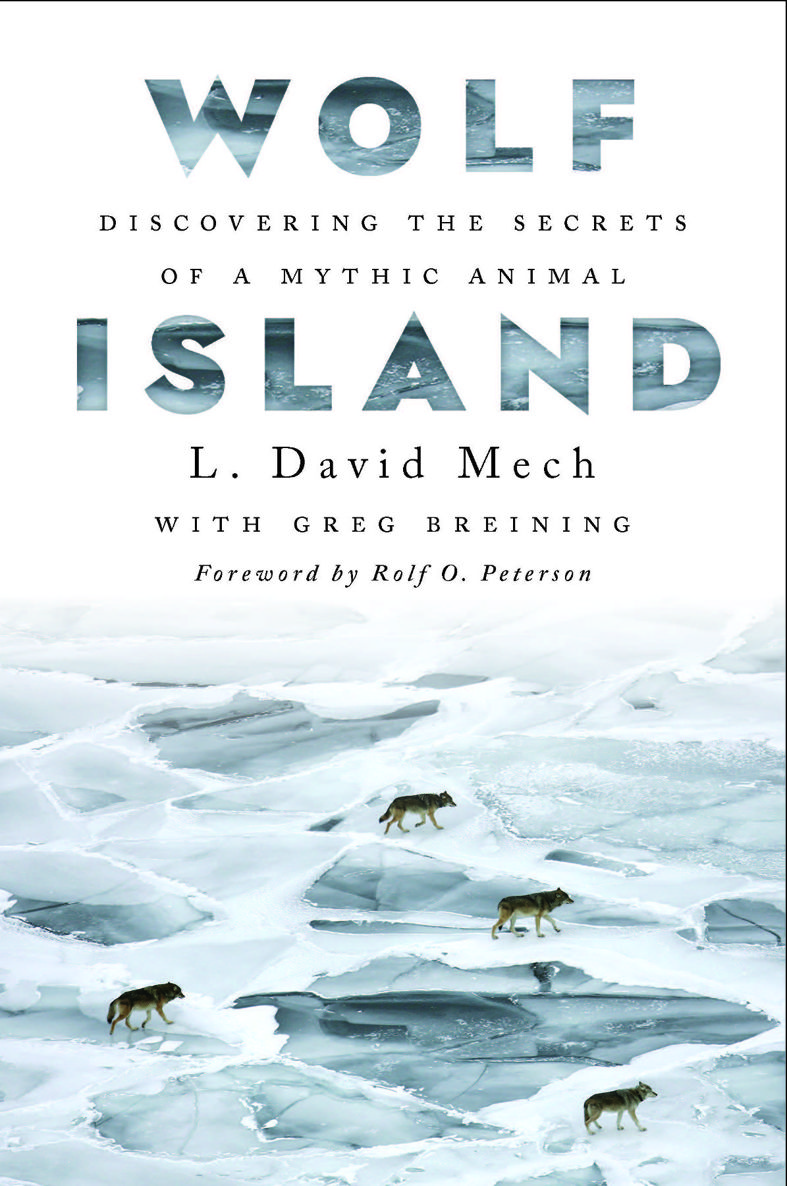

Wolf Island

Also by L. David Mech Published by the University of Minnesota Press

The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species

The Wolves of Denali (with Layne G. Adams, Thomas J. Meier, John W. Burch, and Bruce W. Dale)

Wolf Island

Discovering the Secrets of a Mythic Animal

L. David Mech

with Greg Breining

Foreword by Rolf O. Peterson

University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis

London

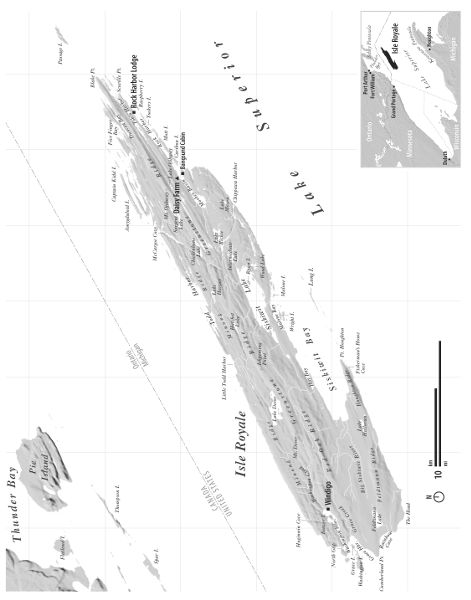

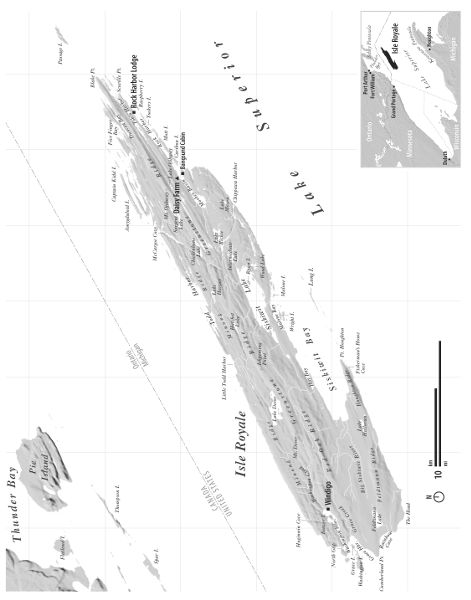

Map of Isle Royale by Brad Herried. All photographs were taken by the author, unless credited otherwise.

Copyright 2020 by Greg Breining

Foreword copyright 2020 by Rolf O. Peterson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

ISBN 978-1-4529-6209-2 (ebook)

A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

For Donald E. Murray (19282014), a superb, skilled bush pilot who served the Isle Royale wolf and moose research project from 1959 to 1979. Don ensured that researchers safely gathered every last piece of information they could glean from the vantage of a light aircraft circling low over the islands bush.

Contents

Rolf O. Peterson

In February 1959, flying in a small plane over Isle Royale National Park, Dave Mech glimpsed primeval nature. Wolves were engaged in a struggle for survival that meant preying on moose, ten times their size. These species have been so engaged through evolutionary time, molding each other, yet we knew little about their relationship until Dave took to the air and witnessed it. Daves initial observations of wolves hunting moose were nothing short of spectacular, and in 1963 millions of readers of National Geographic saw his photographs shot from aircraft and learned about Isle Royale for the first time.

Daves research task, an all-consuming activity for three years, was to figure out the truth about the ability of wolves to kill prey. Would they whittle down the moose population to the point where its survival might be jeopardized? What factors might permit coexistence of predator and prey, both more ancient than the human species? In the superlative observatory that Isle Royale provides, Dave provided outstanding first-cut answers to many important questions. His research established field methods and a foundation that continues to frame research six decades later. Perhaps even more important, Dave was instrumental in creating a sea change in public attitudes about wolves, from evil vermin to respectable fellow travelers. Throughout his career, Dave has worked to discover and share the truth about this remarkable predator.

When I read this memoir of Dave Mechs first three years of wolfmoose fieldwork in Isle Royale National Park, I was reminded anew about the amazing descriptions of wolves hunting in open-forest habitats, the graphic accounts of moose cut down by wolf predation, and the grisly on-the-ground examinations of recently killed moose. For me, the overwhelming impression was, simply, this: trees grow, forests change. The young forests of Daves time, considered prime habitat for moose, following wildfires in 1930s and 1940s, were on the way out in the decades that followed Daves pioneering study. Never again would researchers observe Isle Royale wolves and moose in the young, open forests that Dave witnessed. The same habitats supported sharp-tailed grouse as well, a prairie-edge species that was doomed to disappear as the trees grew.

Indeed, the first wild animal Dave saw on his initial flight in February 1959 was a sharp-tailed grouse, indicated on his penciled flight line on a map that now resides in the University Archives at Michigan Technological University. I marveled at this when I first saw it, as I in turn witnessed the last remaining dancing grounds for this bird when I followed in Daves footsteps little more than a decade later, in the early 1970s. The openings that this bird requires had disappeared, and with that the bird itself died out.

That should have been the fate of moose as well, if the population theories of wildlife biologists of the day had been correct. In the mid-twentieth century the common notion in wildlife ecology was that populations of wild animals were a function of their habitat. The forest fires on Isle Royale in 1936 and 1948 provided optimal habitats for moose for a couple of decades, but then forest succession led to older forests less productive of moose forage, leading to the expectation, written out in my own PhD thesis in 1974, that moose would in turn decline. This is the essence of a bottom-up world.

This is not how things turned out. In 2019, with much older forests and a reduced habitat capacity, there are several times as many moose on Isle Royale as there were sixty years ago. How do we explain that? The answers would require decades of follow-up work, work that is still ongoing in 2020. We now understand, at the risk of oversimplification, that wolves, moose, and vegetation comprise three trophic levels, and each level influences and is influenced by the adjacent levels up and down this simple food chain.

This book highlights the important human element of the research, and here Dave details the privilege and huge responsibility that he undertook. After the first winter flight, Dave wondered if he could last through three winter seasons of being airsick. I wondered the same thing after my first flight in 1971, sitting behind the already legendary pilot Don Murray. Yet the first view of wolves from the back seat of Dons plane has remained one I have never forgotten.

Most appropriately, this book is dedicated to Don Murray, who served as the winter study pilot for nineteen years. His absolute dedication to discovery was a major reason Daves initial three years of research led to something extraordinarythe longest study of a predatorprey system ever undertaken. After 1979, Don was unable to fly after suffering injuries in a car accident, and he was later to lose sight in both eyes. But he never forgot the amazing observations of wolves and moose from his little airplane, recounted with obvious pleasure every time I talked to him, even on the day he died in 2014. The last time Don talked to his grandson, also named Don and by then piloting the winter study at Isle Royale, he said, All I care about are the wolves and moose. With that he passed the torch.

Flying low beneath a sky of leaden stratus clouds, we searched the snowy forest and frozen shoreline of Isle Royale, the 45-mile-long island national park in northern Lake Superior. The leaves were down, of courseit was early February 1960and the aspen and birch sprouted like thin gray hairs above the snow. But for scattered stands of spruce and balsam and pockets of dense cedar in small wetlands, there werent many places a pack of sixteen wolves could hide.

Next page