Foreword

T his is a wonderful memoir of someone who has an extraordinary recollection of interesting things happening around her and who writes about them beautifully.

I have had the privilege of knowing Devaki for well over sixty years. When I first met her, I was struck not only by her joyful presence, but also by her remarkable ability to be easily amused.

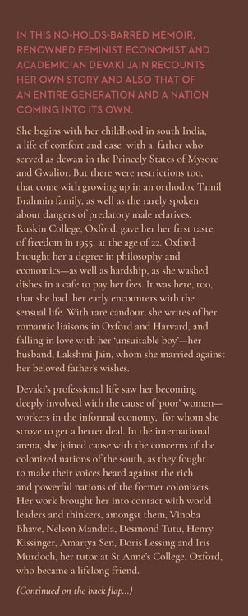

Devaki was a brilliant studenteducated at Mysore University and at Oxford (where she was elected an Honorary Fellow of St Annes College)but her fame far exceeded her formal training. She has been widely known for her unusual insights on the place of women in society, particularly on the reach of inequalities based on gender.

Apart from its originality, the memoir is enriched by the fact that throughout her life, Devaki has been close to people of great interest. Her father knew Mahatma Gandhi who told him on the day before his assassination about his premonition about it. Devaki herself walked with Vinoba Bhave and worked with Jayaprakash Narayan.

As a young woman studying in Oxford, she came to know closely the leading academics therefrom Iris Murdoch to Jennifer Hart, among many others. She became a good friend of such remarkable personalities as Gloria Steinem, with whom she worked on feminist ideas, and Julius Nyerere, who persuaded her to join him in the famous South Commission, to build a less unjust world. She has worked closely with many political leaders in South Africa, including Nelson Mandela, and Desmond Tutu, and with pioneering political thinkers in different parts of Africa, such as Fatema Mernissi.

Of course, among the people whom Devaki came to know well was her extraordinarily talented partnerlater her husbandLakshmi Jain. While each lived exceptional lives of their own, together they built an existence larger than the two combined.

This is a most readable account of experiencesattractively recalled and elegantly presented. It is a splendid addition to the literature on the contemporary world.

July 2020

Amartya Sen

Harvard University,

Massachusetts, US

Authors Note

P ublishing my life at the age of eighty-seven makes me feel somewhat like Samuel Taylor Coleridges ancient mariner.

I fear thee, ancient Mariner! I fear thy skinny hand! And thou art long, and lank, and brown, As is the ribbed sea-sand, says the young man to a mariner he meets. I have skinny wrinkled hands, white grizzly hair and a wrinkled face. Yes, indeed, writing this story of my life has been like coming off a ship, wrecked by a storm, or out of an ancient cave in the mountainside, as everything that I try to remember seems long ago and yet like yesterday.

A journey spanning seven decades of adult life is certainly a long one. It was natural that there were many waves, storms and stillnesses that I witnessed over those eras and I thought my experiences may reveal some new pictures from the big picture, painted by historians. Persons who may have lived, say, seventy adult years in other periods may find my stories trivial or commonplace but that is in fact the excitement of history. That in some ways it is never new, nor ever old!

It is intimidating if not impossible, to even consider writing ones story if one belongs to the era that I belong tothat is the mid-twentieth century. The era was dramatic in many waysbut for us, born in India, it was Indias arrival as a free nation as well as a significant one, not only because of the prime ministership of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, which left its stamp on the world, but also the ingenuity and charismatic leadership of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. How to project what can be called my story in a landscape which was so full of originality, so revolutionary, so full of great characters who walked and scripted the history of free India?

Thus the task that I have undertaken, to write my story, is not only intimidating but even seems ridiculous. Especially since I had no great role to play in this part of Indias history. I was more like an ant, while in fact there were many individuals and movements which were like the elephant or the tiger, or a storm.

To describe how one arrived at a particular point in Indias social history, where one was considered as a pioneering person in terms of the Indian womens movement, does not seem a significant story. Hundreds of other womenand it continues even todayhave made greater contributions than mine to the womens movement as well as to Indias political history. So one again is like an ant.

Yet there was a demand that I should write my story and the demand was backed up by a grant to encourage me to write it, and so here I am, writing it.

The desire to put into words and pages everything that happened to me and that I witnessed has been a pull for decades. At the risk of being laughed at, I would even say I wanted to write about my experiences from the time I was a teenagerI began to keep a diary at the age of twelve. Why this desire to write about what one is experiencing? Could it just be ego? Or the love of writing?

The desire got a big push thanks to the extraordinary, unexpected experience of meeting novelist Doris Lessing in London in 1958. I was introduced to Lessing by another writer, Ann Piper. Lessing was at work then on the pioneering novel published as The Golden Notebook (1962). Radical in both its form and its politics, it tells the story of a writer, Anna Wulf, who finds she is suffering from a peculiar kind of writers block. She can still write, but she cannot find a unified narrative that unites all the episodes in her story. Desperate to overcome this block, she buys herself four notebooks, each with a different-coloured cover. The black notebook will tell the story of her life as a writer, the red notebook her political life, the yellow notebook will have her attempts to make stories out of my experiences, and the blue notebook will serve as a kind of diary.

This strange division of notebooks helps overcome the initial block, but at the end of this exercise she tries something further. She buys a fifth, golden, notebook, which she hopes will serve to unite the four notebooks. This remains a hope, but the sheer effort of working through her life and her experiences gives her a more valuable insight: a sense of what is, realistically speaking, possible.

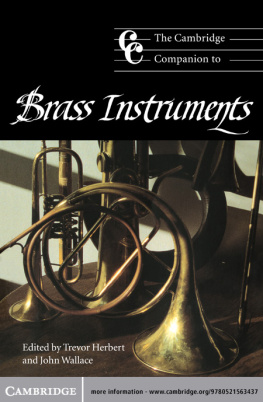

My conversation with Lessing lasted for hours, after which she said to me, You must write your story now. Send it to me, I can help you. I wish I had, but other thingsthe subject of this memoirgot in the way. Sixty years have passed since I first thought of writing my story. In this time, my self-confidence and my skills as a writer have diminished. I hope no longer for perfection, nor to write my own golden notebook. Instead, I am now thinking of another metalpittalai, the word for brass in Tamil, the language of my childhood.