PROLOGUE

The Monomyth

1. Myth and Dream

Whether we listen with aloof amusement to the dreamlike mumbo jumbo of some red-eyed witch doctor of the Congo, or read with cultivated rapture thin translations from the sonnets of the mystic Lao-tse; now and again crack the hard nutshell of an argument of Aquinas, or catch suddenly the shining meaning of a bizarre Eskimo fairy tale: it will always be the one, shape-shifting yet marvelously constant story that we find, together with a challengingly persistent suggestion of more remaining to be experienced than will ever be known or told.

Throughout the inhabited world, in all times and under every circumstance, myths of man have flourished; and they have been the living inspiration of whatever else may have appeared out of the activities of the human body and mind. It would not be too much to say that myth is the secret opening through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into the human cultural manifestation. Religions, philosophies, arts, the social forms of primitive and historic man, prime discoveries in science and technology, the very dreams that blister sleep, boil up from the basic, magic ring of myth.

The wonder is that characteristic efficacy to touch and inspire deep creative centers dwells in the smallest nursery fairy tale as the flavor of the ocean is contained in a droplet or the whole mystery of life within the egg of a flea. For the symbols of mythology are not manufactured; they cannot be ordered, invented, or permanently suppressed. They are spontaneous productions of the psyche, and each bears within it, undamaged, the germ power of its source.

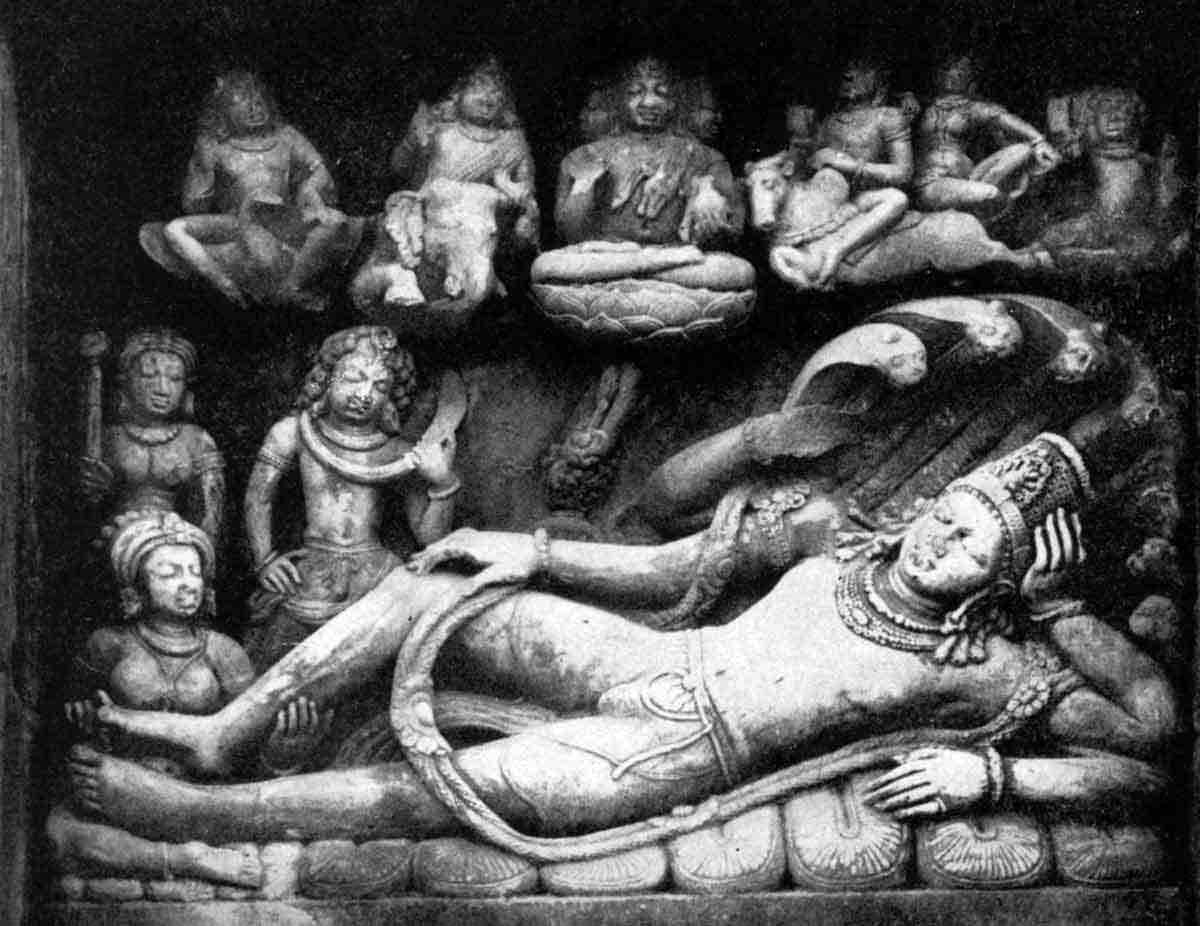

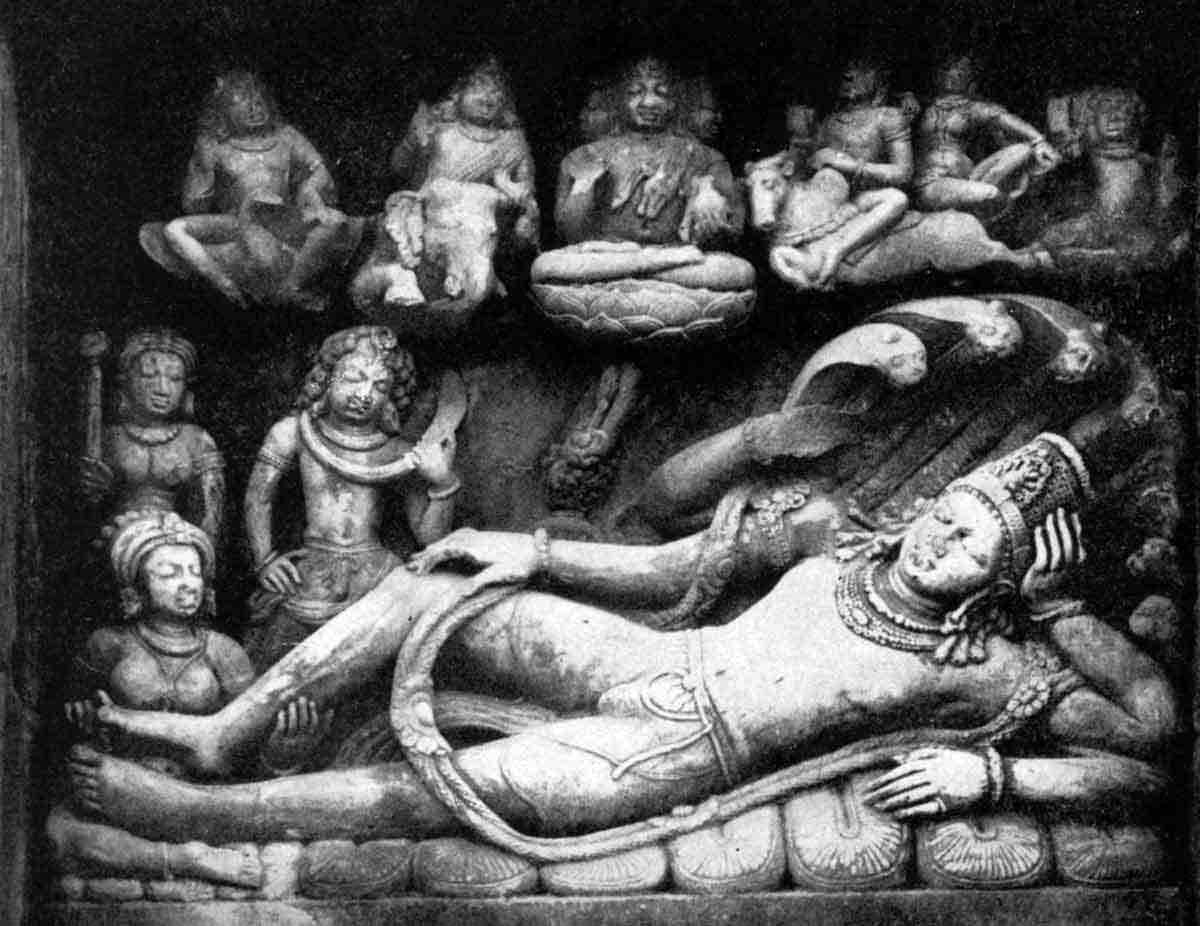

Figure 2.Viu Dreaming the Universe (carved stone, India, c. a.d. 400700)

What is the secret of the timeless vision? From what profundity of the mind does it derive? Why is mythology everywhere the same, beneath its varieties of costume? And what does it teach?

Today many scientists are contributing to the analysis of the riddle. Archeologists are probing the ruins of Iraq, Honan, Crete, and Yucatan. Ethnologists are questioning the Ostiaks of the river Ob, the Boobies of Fernando Po. A generation of orientalists has recently thrown open to us the sacred writings of the East, as well as the pre-Hebrew sources of our own Holy Writ. And meanwhile another host of scholars, pressing researches begun last century in the field of folk psychology, has been seeking to establish the psychological bases of language, myth, religion, art development, and moral codes.

Most remarkable of all, however, are the revelations that have emerged from the mental clinic. The bold and truly epoch-making writings of the psychoanalysts are indispensable to the student of mythology; for, whatever may be thought of the detailed and sometimes contradictory interpretations of specific cases and problems, Freud, Jung, and their followers have demonstrated irrefutably that the logic, the heroes, and the deeds of myth survive into modern times. In the absence of an effective general mythology, each of us has his private, unrecognized, rudimentary, yet secretly potent pantheon of dream. The latest incarnation of Oedipus, the continued romance of Beauty and the Beast, stand this afternoon on the corner of Forty-second Street and Fifth Avenue, waiting for the traffic light to change.

I dreamed, wrote an American youth to the author of a syndicated newspaper feature,

that I was reshingling our roof. Suddenly I heard my fathers voice on the ground below, calling to me. I turned suddenly to hear him better, and, as I did so, the hammer slipped out of my hands, and slid down the sloping roof, and disappeared over the edge. I heard a heavy thud, as of a body falling.

Terribly frightened, I climbed down the ladder to the ground. There was my father lying dead on the ground, with blood all over his head. I was brokenhearted, and began calling my mother, in the midst of my sobs. She came out of the house, and put her arms around me. Never mind, son, it was all an accident, she said. I know you will take care of me, even if he is gone. As she was kissing me, I woke up.

I am the eldest child in our family and am twenty-three years old. I have been separated from my wife for a year; somehow, we could not get along together. I love both my parents dearly, and have never had any trouble with my father, except that he insisted that I go back and live with my wife, and I couldnt be happy with her. And I never will.

The unsuccessful husband here reveals, with a really wonderful innocence, that instead of bringing his spiritual energies forward to the love and problems of his marriage, he has been resting, in the secret recesses of his imagination, with the now ridiculously anachronistic dramatic situation of his first and only emotional involvement, that of the tragicomic triangle of the nursery the son against the father for the love of the mother. Apparently the most permanent of the dispositions of the human psyche are those that derive from the fact that, of all animals, we remain the longest at the mother breast. Human beings are born too soon; they are unfinished, unready as yet to meet the world. Consequently their whole defense from a universe of dangers is the mother, under whose protection the intra-uterine period is prolonged.

The unfortunate father is the first radical intrusion of another order of reality into the beatitude of this earthly restatement of the excellence of the situation within the womb; he, therefore, is experienced primarily as an enemy. To him is transferred the charge of aggression that was originally attached to the bad, or absent mother, while the desire attaching to the good, or present, nourishing, and protecting mother, she herself (normally) retains. This fateful infantile distribution of death (thanatos: destrudo) and love (eros: libido) impulses builds the foundation of the now celebrated Oedipus complex, which Sigmund Freud pointed out some fifty years ago as the great cause of our adult failure to behave like rational beings. As Dr. Freud has stated it: King Oedipus, who slew his father Laus and married his mother Jocasta, merely shows us the fulfilment of our own childhood wishes. But, more fortunate than he, we have meanwhile succeeded, in so far as we have not become psychoneurotics, in detaching our sexual impulses from our mothers and in forgetting our jealousy of our fathers.

For many a man hath seen himself in dreams

His mothers mate, but he who gives no heed

To such like matters bears the easier fate.

The sorry plight of the wife of the lover whose sentiments instead of maturing remain locked in the romance of the nursery may be judged from the apparent nonsense of another modern dream; and here we begin to feel indeed that we are entering the realm of ancient myth, but with a curious turn.

I dreamed, wrote a troubled woman,

that a big white horse kept following me wherever I went. I was afraid of him, and pushed him away. I looked back to see if he was still following me, and he appeared to have become a man. I told him to go inside a barbershop and shave off his mane, which he did. When he came out he looked just like a man, except that he had horses hoofs and face, and followed me wherever I went. He came closer to me, and I woke up.

I am a married woman of thirty-five with two children. I have been married for fourteen years now, and I am sure my husband is faithful to me.