ALSO BY BENJAMIN M. FRIEDMAN

The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth

Day of Reckoning: The Consequences of American Economic Policy Under Reagan and After

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2021 by Benjamin M. Friedman

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of PenguinRandom House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Friedman, Benjamin M., author.

Title: Religion and the rise of capitalism / Benjamin M. Friedman.

Description: New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: lccn 2020010391 (print) | lccn 2020010392 (ebook) |

isbn 9780593317983 (hardcover) | isbn 9780593317990 (ebook)

Subjects: lcsh : EconomicsReligious aspects. | Religious thoughtHistory. | CapitalismReligious aspects.

Classification: lcc hb 72 . f 745 221 (print) | lcc hb 72 (ebook) | ddc 330.12/2dc23

lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020010391

lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/20200

Ebook ISBN9780593317990

Cover image: High Street, Edinburgh, (detail) by Joseph Mallord William Turner. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

Cover design by Tyler Comrie

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

Again for B.A.C.

Love, always

Contents

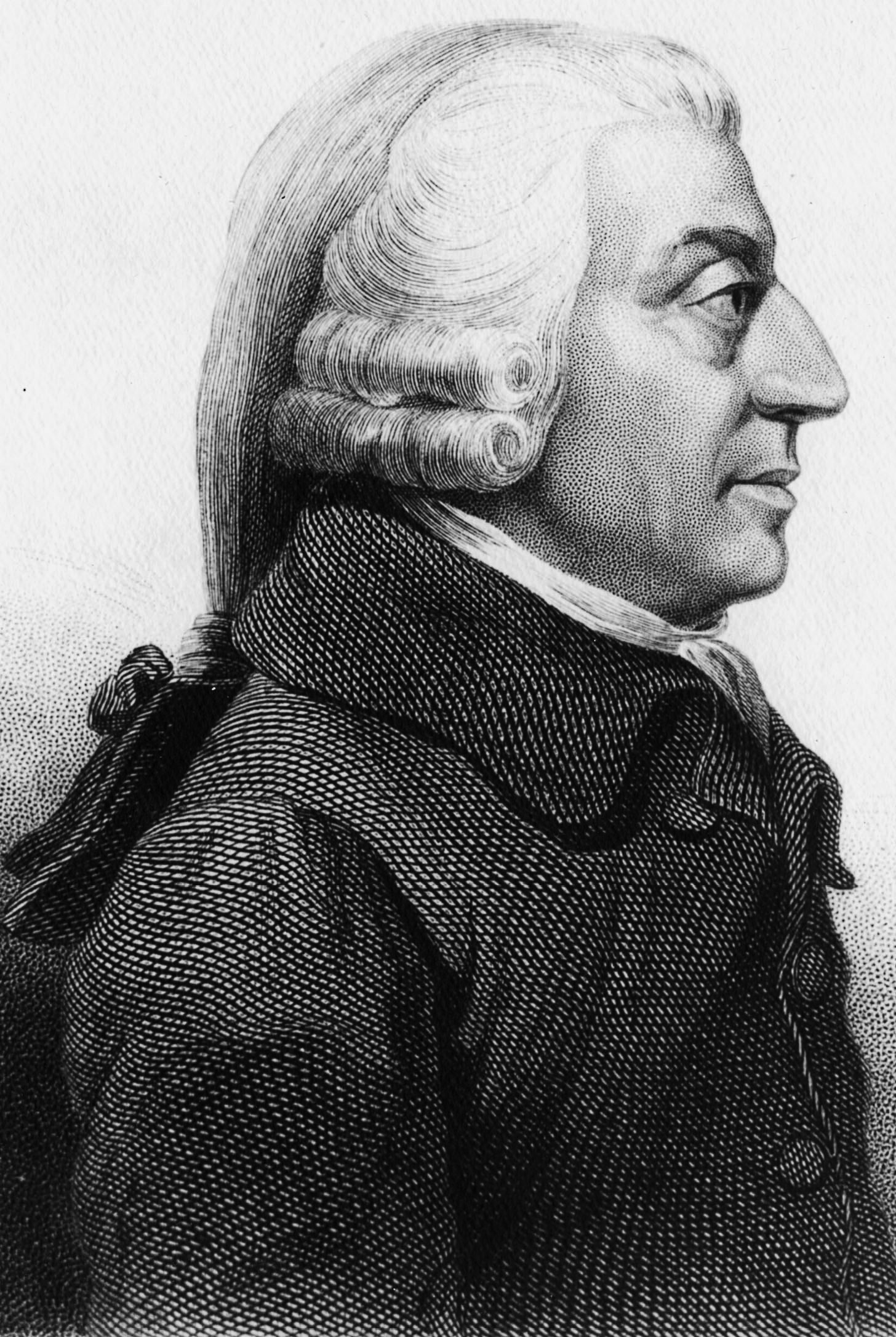

Adam Smith (17231790)

Introduction

Where do our ideas about how the economy works, and our views on economic policy, come from? Most people in the Western world, and especially in America, simply take for granted that we organize one of the most essential aspects of human activitythe economic sphereprimarily around private initiative channeled through markets. But where did that presumption come from? And why do so many people, again especially Americans, often see any challenge to our market-centered conduct of economic affairs as a fundamental threat to our way of life?

The economist John Maynard Keynes famously suggested that the thinking of even the most practically minded people, who believe they are exempt from any influence from the world of ideas, is nonetheless the product of what economists and other academic thinkers said some time before. Why economists think as they do matters as well.

The central argument of this book is that our ideas about economics and economic policy have long-standing roots in religious thinking. Most of us are unaware of how religious ideas shape our economic thinking, and when such links are occasionally suggested they are mostly misunderstood. But religionnot just the daily or annual cycle of ritual observances, but the inner belief structure that forms an essential part of peoples view of the world in which they livehas shaped human thinking since before there were written words to record it. In this book I argue that the influence of religious beliefs on modern Western economics has been profound, and that it remains important today. Critics of todays economics sometimes complain that belief in free markets, among economists and many ordinary citizens too, is itself a form of religion. It turns out that there is something to the idea: not in the way the critics mean, but in a deeper, more historically grounded sense.

But the point is more than just a matter of the history of ideas. The influence of religious thinking also bears on how Americans today, along with citizens of other Western countries, think about many of the most highly contested economic policy issues of our time. This connection between peoples economic views and religious beliefsoften including religious beliefs that they do not personally holdstems from before the creation of the American republic, and it runs to the core of how economics came to be the line of thinking we know today. It also helps explain what we often view as the puzzling behavior of many of our fellow citizens whose attitudes toward questions of economic policy seem sharply at odds with what would be to their own economic benefit.

The foundational transition in thinking about what we now call economicsthe transition that we rightly associate with Adam Smith and his contemporaries in the eighteenth centurywas importantly shaped by what were then new and vigorously contended lines of religious thought within the English-speaking Protestant world. The resulting influence of religious thinking on modern economic thinking, right from its origins, established resonances that then persisted, albeit in evolving form as the economic context changed, the questions economists asked shifted, and the analytical tools at their disposal expanded, right through the twentieth century. Although for the most part we are not consciously aware of themthis is why their consequences seem puzzling whenever we stumble across themespecially in America these lasting resonances with religious thinking continue to shape our current-day discussion of economic issues and our public debate over questions of economic policy.

I am well aware that the idea of a central influence of religion on Adam Smiths thinking, or on that of many of his contemporaries, will initially strike many knowledgeable readers as implausible on its face. Smiths great friend David Hume, who also played a key role in the creation of modern economics, was an avowed skeptic and an outspoken opponent of organized religion; Hume notoriously referred to Church of England bishops as Retainers to Superstition. Smith, as far as we can tell, was at best a deist of the kind Americans identify with Thomas Jefferson. There is little evidence of Smiths active religious participation, much less religious enthusiasm. My argument is most certainly not that these were religiously dedicated men who self-consciously brought their theological commitments to bear on their economic thinking.

Rather, the creators of modern economics lived at a time when religion was both more pervasive and more central than anything we know in todays Western world. And, crucially, intellectual life was more integrated then. Not only were the sciences and humanities (to use todays vocabulary) normally discussed in the same circles, and mostly by the same individuals, but theology too was part of the ongoing discussion. Part of what Smith taught, as a professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow, was natural theology. He and his colleagues and friends were continually exposed to what were then fresh debates about new lines of theological thinking. I argue that what they heard and read and discussed influenced the economics they produced, just as the ideas of todays economists are visibly shaped by what we learn from physics, or biology, or demography.

This idea importantly changes our view of the historical process by which the Western world arrived at todays economics. The conventional account is that the line of thinking we know today as economics was a product of the Enlightenment: more specifically, that the Smithian revolution and the subsequent development of economics as an intellectual discipline were part of the process of secular modernization in the sense of a historic turn from thinking in terms of a God-centered universe toward what we now broadly call humanism. Nicholas Phillipson, in his prize-winning biography of Adam Smith, referred to one statement of Smiths as a reminder that not just