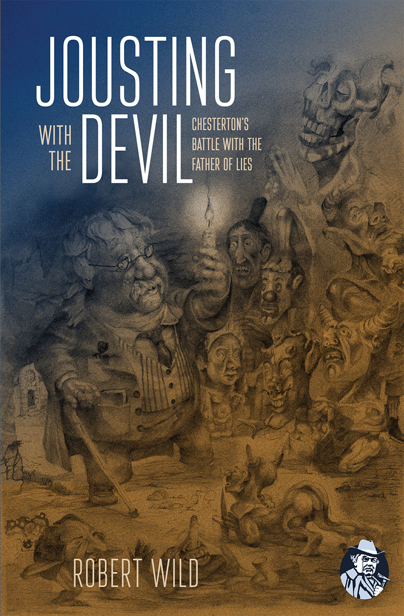

2014 The American Chesterton Society Printed in the United States of America Cover illustration by Nicholas Blicharski Cover and Interior design by Ted Schluenderfritz LCCN: 2014944519 ISBN: - - 9744495 - -

To Stratford Caldecott

A great Chestertonian, a great Catholic, and a great person

Knight of the Holy Ghost

Wisdom his motley, Truth his loving jest;

The mills of Satan keep his lance at play,

Pity and innocence his heart at rest.

This is Gods universe all right,

but there is the enemy.

Letter to W.R. Titterton

It is that the exorcist towers above the poet and even the prophet; that the story between Cana and Calvary is one long war with demons. He understood better than a hundred poets the beauty of the flowers of the battle-field; but he came out to battle. And if most of his words mean anything they do mean that there is at our very feet, like a chasm concealed among flowers, an unfathomable evil. G.K. Chesterton, The New Jerusalem In your book just published you tell us what is wrong with the world. As I havent read the book yet, would you mind telling me what is wrong? The Devil. (Interview with Chesterton in Los Angeles Times , August , 1910 ) The finding and fighting of positive evil is the beginning of all funand even of farce. G.K. Chesterton, The Flying Inn

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xiii

Poem by Walter de la Mare on the service sheet for Chestertons funeral.

INTRODUCTION

The Battle with the Dragon

Satan is real. Thats the first thing. The second thing should then be obvious: Satan is horrible. But the third thing may not be obvious: Satan is also ridiculous. But he is the only ridiculous thing that must be taken seriously.

This book explores G.K. Chestertons encounter with the reality that is Satan. Whether or not you are familiar with Chesterton, you will be surprised at how familiar Chesterton is with this subject. Though he seems to have an intuitive sense of truth whatever his subject matter, when Chesterton writes about the Devil, he knows what he is talking about for more than intuitive reasons because his wisdom is supplemented by personal experience. And therein lies the surprise.

Chesterton is certainly known for his jollity, but also for his jousting. He set the tone with his first book of essays, The Defendant , establishing himself as a fighter, but a fighter on the side that is being attacked. He is one who defends the good when it is attacked by the bad, the normal when it is attacked by the abnormal, the princess when she is attacked by the dragon. He next made his name as a defender of orthodoxy. And a decade after he wrote a book by that name, he explained the significance of that word: Orthodoxy never stood more for normality than in affirming that evil and not good is the usurper in the universe.

Satan is the usurper in the universe, trying to rule what is not his to rule. The universe is not his; he did not make it. The Devil cannot make anything but can only destroy, he does not satisfy but can only tempt, he cannot impart wisdom, only doubt. Says Chesterton: I could fancy that men drew the Tempter with the curves of a serpent because they can be twisted into the shape of a question mark.

Why is it that we are often drawn to doubt, drawn to the Devil? The Devil is the one who will not subject himself to God, but who tries to take the place of God. The Devil is he who says he is God. That is, he is one who says that his functions are infinite and cannot be judged. That is the great temptation, to think that we can do whatever we want and not suffer any consequences for it.

It is a reality we constantly deny. We try to snake our way around it. We have substituted the Beast for the Devil and in the process convinced ourselves that the idea of the Devil is a fancy that comes from a beast, a beast that is merely myth. It is the learned professors point that the dragon evolved into the devil, but I think it far better psychology, as well as theology, to say that the devil took the form of the dragon.

Chesterton gives a much better account of where the Dragon comes from:

There is a certain conception of the place of evil in life which I will call, by way of convenient symbol, the conception of St. George and the Dragon. The Dragon is bigger than St. George. He may look big enough to fill the world; but he is not the world; nor, above all, did he make the world. The stars are not the sparks from his flaming mouth, nor the clouds the smoke from his nostrils. The shadow of him may be big enough to blot out the world; but he is only a big blot on the world. The very effort to clear him away implies that there is something to be cleared. The stars, the air, the abstract truths, being itself and the breath of life, these exist anterior to and apart from the largest dragon; and exist in a sort of primordial innocence. This idea exists as an instinct in all healthy and hopeful attacks upon evil. But this idea as a philosophy is not identical with all philosophies. It is not the same as the pessimist philosophy, in which the dragon is the creator of all, who has only created St. George as a clockwork doll to play with and to break. It is not the same as the optimist philosophy, which explains away the dragon merely as the shadow of St. George; the long fantastic shadow of himself that gets on his nerves at twilight. It is not the same as a sort of Buddhist philosophy, which sees the evil only in the fact that the man and the monster are two things and not one; and thinks that all will be well when one of them swallows the other; the begging being rather on the dragon. It is not even the same as a promethean progressive philosophy, of something being evolved that will educate and improve an indifferent universe; or in other words the dragon is St. Georges grandmother, but that he will be sufficiently enlightened to teach his grandmother. It is something quite different from all these, as we find if we attempt to define it; but whenever we are most sane we act upon it. I do not say that the more heroic heathens did not act upon it, before it was formed; they did. I do not say that the more healthy agnostics do not now act on it without defining it; they do. But I say this; that the more we do attempt to define it, the more we analyse it logically and state it lucidly, the more exactly we distinguish it from other moods of other minds, the more closely we shall find it approximating to the most dogmatic and disputed parts of what was called the theology of the Dark Ages; the nearer we shall come to the whole strange story of the treason of the archangel, of his betrayal of a divine plan, of his relative success and his ultimate failure. The shortest way of stating it is that evil is a tyranny, but it is also a temptation. Millions even in modern times act on that normal morality; millions do not reduce it to any philosophy; but if it is reduced to any philosophy it must be to this and no other.

Chesterton rises above platitudes and even niceties and plunges into profound theology. That is the other surprise: that this journalist, this jouster, should oppose evil to its face and tell the eternal truths so plainly and so pointedly for the daily reader of throwaway newspapers. The Father of Lies would like us to think that truth evolves and even evaporates. But Chestertons words survive because truth does not change, and truth is our only weapon against the lie.

As this book demonstrates, G.K. Chesterton is still swinging his sword. The horrible thing must be ridiculed, that is, it must be put in its place. But the battle to defeat the Dragon is serious business indeed.

Next page

2014 The American Chesterton Society Printed in the United States of America Cover illustration by Nicholas Blicharski Cover and Interior design by Ted Schluenderfritz LCCN: 2014944519 ISBN: - - 9744495 - -

2014 The American Chesterton Society Printed in the United States of America Cover illustration by Nicholas Blicharski Cover and Interior design by Ted Schluenderfritz LCCN: 2014944519 ISBN: - - 9744495 - -