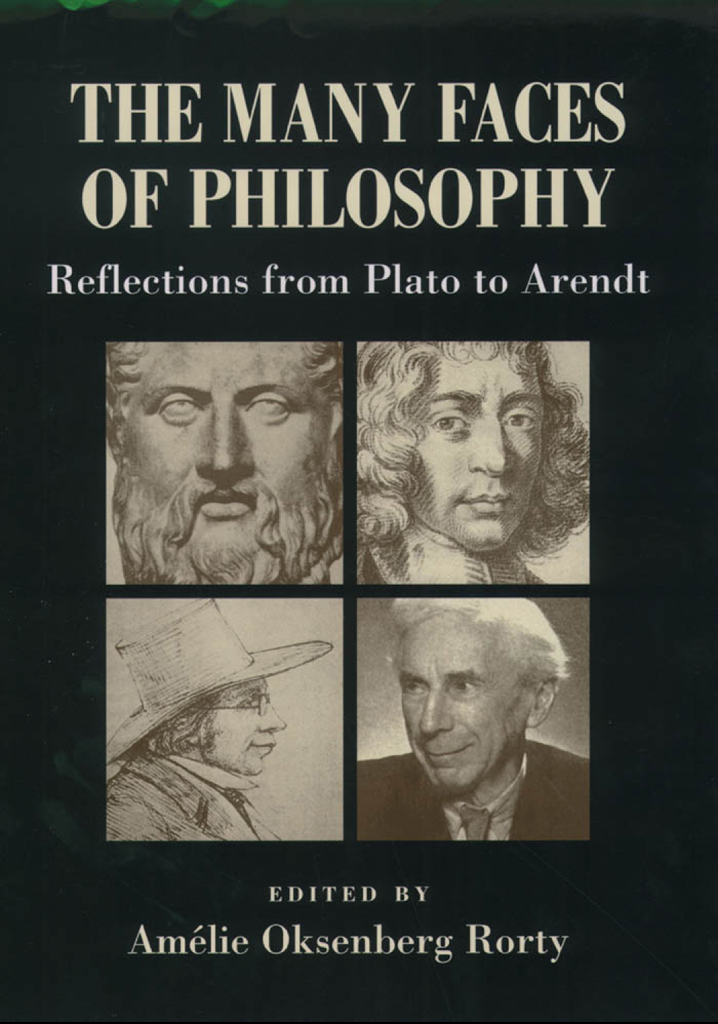

The Many Faces of Philosophy

The Many Faces of Philosophy

Reflections from Plato to Arendt

Edited by

Amlie Oksenberg Rorty

2003

OxfordNew York

AucklandBangkokBuenosAires

Cape TownChennaiDar es SalaamDelhiHong KongIstanbul

KarachiKolkataKuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityMumbai

NairobiSo PauloTaipeiTokyoToronto

Copyright 2003 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The many faces of philosophy : reflections from Plato to Arendt /

[compiled by] Amlie Oksenberg Rorty.

p. cm.Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-19-513402-8

1. Philosophy.I. Rorty, Amlie.

B72 .M346 2003 100dc212002030342

In gratitude to

Matthew Carmody

Genevieve Lloyd

Jay Rorty

Contents

The philosophers represented in this collection have, for better or worse, influenced the way philosophy is practiced. They have formed the canon that presently defines the field, guides apprentices, and sets standards of authority. The scope of their meditative self-presentations nevertheless suggests that philosophy has not formed a specific genre of writing or argumentation. Philosophical credos, manifestos, and programs are found in letters, prefaces, journals, diaries, interviews. Moreover, the aims, the stylistic conventions, and the audiences of such self-conscious self-mirrorings vary historically. Many of Augustines reflections were formulated as prayers. Montaignes Essais are exercises: expansive, concentric attempts to present himself to his intimate friends, as if he were speaking to himself. Other autobiographiesthose of Al Ghazali, Maimonides, and Descartesfollow a narrative form, a reconstructed story of an intellectual quest that moves them from sensory experience through skepticism toward an affirmation of the consonance of faith and science. Later philosophical autobiographiesfor instance, those by Hobbes and Humeintroduce a different narrative mode of self-examination. Rousseaus artful attempts at spontaneity announce a new form of autobiographical writing. And when self-conscious intellectual autobiographies are continuous with philosophical polemicsas they are with Heidegger, Russell, and Carnapthe genre philosophical autobiography yet again takes a different style, agenda, and audience.

The modes of philosophy are as various as those of autobiography. As their aims, issues, and audiences vary, philosophers experiment with different argumentative rhetorical and literary genres. In doing so, they often realign themselves: sometimes they keep company with theologians, sometimes with scientists or historians, sometimes with statesmen and educators, journalists and citizens of the republic of letters. Most recently, philosophy has become an academic profession, an exclusive, self-selective, and self-perpetuating guild with strict rules of apprenticeship and membership, a guild that regulates acceptable philosophic publication.

The Many Faces of Philosophy marks the intersection between continuously transforming genres. The introduction questions the rigid distinctions between philosophy, autobiography, literary essays, and political argumentation, distinctions that emerged from the practical necessities of library and publishers cataloguesand from the departmental politics of university organization. It presents philosophers meditations on the nature and tasks of philosophy, their reflections on the contribution that their strictly philosophic work makes to their other activities and commitments as political or spiritual advisers, as scientists and educators. Those self-searching meditations include materials culled from letters, prefaces, memoirs, political tracts, replies to critics. They also include a few excerpts from contemporary biographies (Baillet on Descartes, Aubrey on Hobbes, Fox Bourne on Locke, Adam Smith on Hume, Engels on Marx).

I have not included technical philosophical discussions (Spinoza on the vortex; Leibniz on the infinite). Nor I have I included personal letters, letters of condolence, love letters (Darling, our marriages are out of town, meet me at lHtel dAmour), letters of recommendation (Schmuel Potsdam is the best student weve had since Leibniz), pleas for money or patronage (Greatest Protector of Learning, please send money) or ordinary whining (Did you see the disgusting mis-review of my latest book by that envious idiot?).

I have omitted well-known, carefully crafted philosophical autobiographiesfor instance, those of Marcus Aurelius, Augustine, Boethius, Rousseau, Mill, Sartre, and Russell. They are readily available in inexpensive paperback editions, and it would be a travesty to edit such works. Instead I have included shorter, less well known works by many of these authors.

There are glaring omissions. Aristotle: we only have his will and a poem honoring Plato, neither of philosophical interest. Aquinas: to the best of my knowledge, we unfortunately have no autobiographical scraps of any kind. Asian and African philosophers: it would require another book to present them, one prepared by scholars specialized in those rich and varied traditions.

Knowledgeable readers of a book of this kind will inevitably regret some selections: why Seneca rather than Cicero? why so much of Augustines correspondence with St. Jerome and so little of his reflections on political theory? surely there are better passages from Rousseau, from Hegel? And I, too, as I read proofs, thought: Oh, if I could only have included some delicious material from Plotinus or from Boethius! I can only hope that our shared disappointments send us to the originals, each of us editors of a book we would have preferred.

Peter Ohlin, our editor at Oxford University Press, rightly thought we should introduce each philosopher with a brief biographical note. In despair at doing justice to the subject, I turned for help to a team of expert colleagues, who (understandably enough) preferred to remain anonymous. On behalf of our readers, I am grateful to them for their resourceful and conscientious work in writing the headnotes.

The initial skeletal table of contents was circulated with a request for comments and suggestions, additions and editions to colleagues, specialists in ancient and medieval philosophy (Myles Burnyeat, Steven Harris, Simon Harrison, Matthew Kraus), in early modern philosophy (Frederick Beiser, Daniel Garber, Stephen Gendzier, Genevieve Lloyd, Terence Pinkard, James Schmidt, Sally Sedgwick, Jacqueline Taylor, Kenneth Winkler, Arnulf Zweig), in contemporary analytic and continental philosophy (Seyla Benhabib, William Bristow, James Dwyer, Juliet Floyd, Mary Mothersill, Ronald de Sousa). Several colleagues (Seyla Benhabib, Sissela Bok, Tracy Kosman, Mary Mothersill, Sara Ruddick, William Ruddick, Sally Sedgwick) insisted on the inclusion of at least some women philosophers. Sissela Bok generously showed me her Autobiography as Moral Background. Jacob Dreyfack let me use his translation of Bailliet. I am grateful to Jeffrey Michels, Charles McKinley, and Scott Ruescher for their bibliographical and technical help, and to Peter Ohlin for his editorial acumen. Byron Good of the Department of Social Medicine at Harvard University, Williams College and the members of its philosophy department offered me ideal conditions for study and writing. In truth, a work of this kind is a cooperative enterprise that draws on the expertise of a host of generous and helpful colleagues. Without their knowledge and their critical and empathic imagination, and without their collaboration in preparing biographical notes, this book would not exist.