This book made available by the Internet Archive.

Acknowledgments

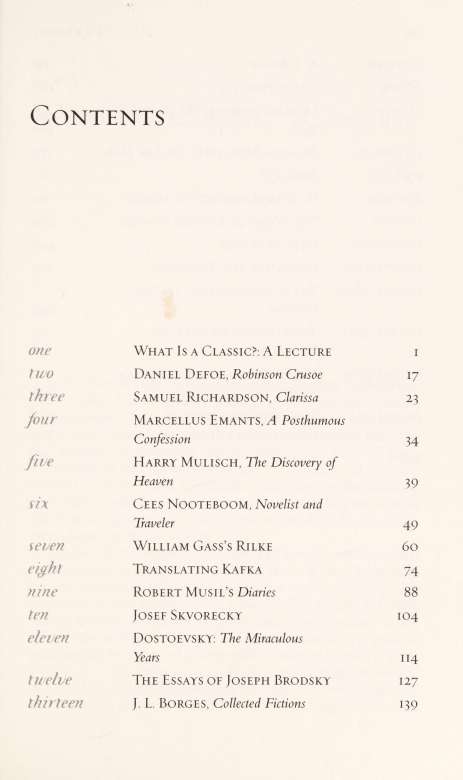

What Is a Classic? was given as a lecture in Graz, Austria, in 1991, and published in Current Writing (1993).

The essay on Defoe first appeared as the introduction to the 1999 Worlds Classics edition of Robinson Crusoe and is reprinted by kind permission of Oxford University Press.

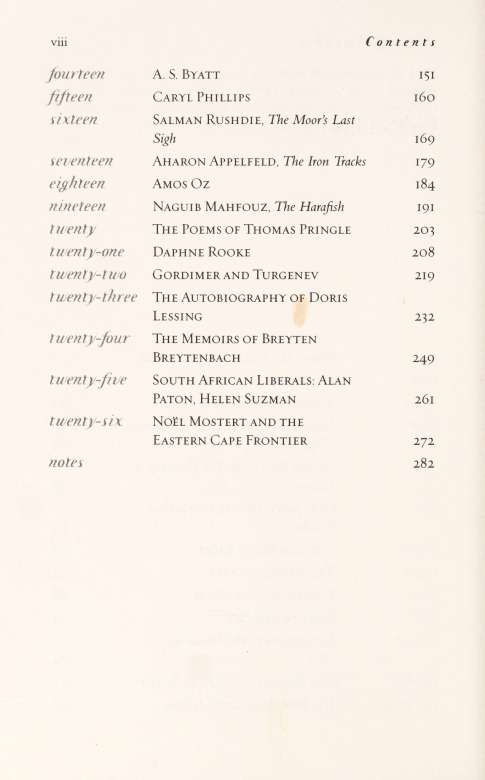

The essay on Rooke first appeared as an afterword to the 1991 Penguin edition of Mittee and is republished by kind permission of Penguin U.K.

The essay on Emants first appeared as the introduction to my translation of A Posthumous Confession (London: Quartet Books, 1986).

The essay on Paton first appeared in New Republic in 1990, that on Pringle in Research in African Literatures in 1990, and that on Gordimer and Turgenev in South African Literary History: Totality and/or Fragment, ed. Erhard Reckwitz, Karin Reitner, and Lucia Vennarini (Essen: Die Blaue Eule, 1997).

The essay on Richardson was first given as a lecture at the University of Chicago in 1995.

All other essays first appeared in the New York Review of Books and are reprinted by kind permission of the publishers. Dates

VI

Acknowledgments

are as follows: Mostert, Suzman in 1993; Breytenbach in 1993 and 1999; Mahfouz, Lessing in 1994; Frank in 1995; Brodsky, Rushdie, Byatt, Skvorecky in 1996; Mulisch, Nooteboom, Phillips in 1997; Appelfeld, Oz, Kafka, Borges in 1998; Musil, Gass in 1999.

What Is a Classics a Lecture

i

In October of 1944, as Allied forces were battling on the European mainland and German rockets were falling on London, Thomas Stearns Eliot, aged fifty-six, gave his presidential address to the Virgil Society in London. In his lecture Eliot does not mention wartime circumstances, save for a single referenceoblique, understated, in his best British mannerto accidents of the present time that had made it difficult to get access to the books he needed to prepare the lecture. It is a way of reminding his auditors that there is a perspective in which the war is only a hiccup, however massive, in the life of Europe.

The title of the lecture was What Is a Classic? and its aim was to consolidate and reargue a case Eliot had long been advancing: that the civilization of Western Europe is a single civilization, that its descent is from Rome via the Church of Rome and the Holy Roman Empire, and that its originary classic must therefore be the epic of Rome, Virgils Aeneid 4 Each time this case was reargued, it was reargued by a man of greater public authority, a man who by 1944, as poet, dramatist, critic, publisher, and cultural commentator, could be said to dominate English letters. This man had targeted London as the metropolis of the English-speaking world,

Stranger Shores

and with a diffidence concealing ruthless singleness of purpose had made himself into the deliberately magisterial voice of that metropolis. Now he was arguing for Virgil as the dominant voice of metropolitan, imperial Rome, and Rome, furthermore, imperial in transcendent ways that Virgil could not have been expected to understand.

What Is a Classic? is not one of Eliots best pieces of criticism. The address de haut en has, which in the 1920s he had used to such great effect to impose his personal predilections on the London world of letters, has become mannered. There is a tiredness to the prose, too. Nevertheless, the piece is never less than intelligent, andonce one begins to explore its backgroundmore coherent than might appear at first reading. Furthermore, behind it is a clear awareness that the ending of World War II must bring with it a new cultural order, with new opportunities and new threats. What struck me when I reread Eliots lecture in preparation for the present lecture, however, was the fact that nowhere does Eliot reflect on the fact of his own Americanness, or at least his American origins, and therefore on the somewhat odd angle at which he comes, honoring a European poet to a European audience.

I say European, but of course even the Europeanness of Eliots British audience is an issue, as is the line of descent of English literature from the literature of Rome. For one of the writers Eliot claims not to have been able to reread in preparation for his lecture is Sainte-Beuve, who in his lectures on Virgil claimed Virgil as the poet of all Latinity, of France and Spain and Italy but not of all Europe. 2 So Eliots project of claiming a line of descent from Virgil has to start with claiming a fully European identity for Virgil; and also with asserting for England a European identity that has sometimes been begrudged it and that it has not always been eager to embrace. 3

Rather than follow in detail the moves Eliot makes to link Virgils Rome to the England of the 1940s, let me ask how and why Eliot himself became English enough for the issue to matter to him. 4

Why did Eliot become English at all? My sense is that at first the motives were complex: partly Anglophilia, partly solidarity with the English middle-class intelligentsia, partly as a protective

What Is a Classic?

disguise in which a certain embarrassment about American barbarousness may have figured, partly as a parody, from a man who enjoyed acting (passing as English is surely one of the most difficult acts to bring off). I would suspect that the inner logic was, first, residence in London (rather than England), then the assumption of a London social identity, then the specific chain of reflections on cultural identity that would eventually lead him to claim a European and Roman identity under which London identity, English identity, and Anglo-American identity were subsumed and transcended. 5

By 1944 the investment in this identity was total. Eliot was an Englishman, though, in his own mind at least, a Roman Englishman. He had just completed a cycle of poems in which he named his forebears and reclaimed as his own East Coker in Somersetshire, home of the Elyots. Home is where one starts from, he writes. In my beginning is my end. What you own is what you do not ownor, to put it another way, what you do not own is what you own. 6 Not only did he now assert that rootedness which is so important to his understanding of culture, but he had equipped himself with a theory of history in which England and America were defined as provinces of an eternal metropolis, Rome.