LakoffGeorge - Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide

Here you can read online LakoffGeorge - Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Societas, genre: Science / Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide

- Author:

- Publisher:Societas

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

LakoffGeorge: author's other books

Who wrote Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Your Brains Politics How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide George Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling

SOCIETAS

essays in political

& cultural criticism

imprint-academic.com

2016 digital version converted and published by

Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

Copyright George Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling, 2016

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism and discussion.

Imprint Academic, PO Box 200, Exeter EX5 5YX, UK

First published in German by Carl-Auer Publishers, Heidelberg, Germany, 2008

To Kathleen and to Eve

A Note About This BookOver the past decades, research in cognitive science and linguistics has uncovered astounding facts about the human mind. This is a dialogical introduction to these findings and their implications for politics.

Enjoy!

George Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling

Berkeley, August 2016

1. Normal Thought: Reasoning in Metaphors 1.1. The Embodied Mind: Things we dont know about our reasoning Elisabeth Wehling (E.W.) You once wrote that metaphors can start wars, and that the second Gulf War and Iraq War were largely motivated by metaphors.How on earth do cognitive linguists come to ascribe this much power to a harmless, rhetoric device? George Lakoff (G.L.) It has to do with how our brains function. We all reason about the world largely in terms of metaphor. Metaphors are omnipresent, and not just in political discourse. They structure peoples everyday language and reasoning. There is not a single political issue that we can reason about in entirely literal terms, without using metaphor. Peoples understanding of the world is largely metaphoric, day in and day out. E.W. What is startling is the fact that folks dont know this, that they are completely unaware of this fact about their own reasoning. But then again, most people hold quite a few entirely false assumptions about how their minds work. G.L. Exactly. Lets go through the four biggest mistaken assumptions about human thought.First, people assume that thought is conscious. Well, thats wrong. Most thought, an estimated 98 percent, is completely unconscious.Second, a lot of us believe that human rationality is a thing that exists somehow independent of our bodies. Thats also not true. Reasoning is a physical process that depends on our bodies and the physical realities of our brains.Third, many folks hold that reasoning is universal, meaning that all people reason in the same way. Wrong again. People do not all share one universal way of reasoning. They reason about the world differently, partly because their minds have acquired distinctive structures through their cultural and individual experiences.Fourth, people believe that humans can understand things as they literally exist in the world, and that they can talk about them in an objective way. Well, thats not true. We reason and speak in terms of metaphor all the time without noticing it. Abstract ideas, for instance, cannot readily be reasoned or talked about in any truly meaningful way without the use of metaphor.Thus, in order to understand how metaphors define political thought and actionand how they can in fact lead to warfare between nationswe need to consider the basic mechanisms of human cognition. How do we understand the world around us on an everyday basis? Well, more often than not, in terms of metaphor. E.W. That sounds nothing like the conventional understanding of metaphors, which is that they are a matter of language and language only. Aristotle, for instance, described metaphor as an artistic form of language. G.L. Most people think of metaphor as a matter of words and language, and that conception has spanned over 2,500 years of Western scholarship. But over the past four decades, cognitive science research has brought about groundbreaking findings that force us to change many of our traditional assumptions about how human language and thought work.Today we know that metaphors are by no means a matter of language and language only. Metaphors structure our everyday cognition, our perception of reality. They are a matter of thought, they are a matter of language, and they are a matter of actions. E.W. Our readers might say: Language? Sure. Thought? Maybe. But actions? G.L. And from where do our actions emerge, if not from our thoughts? E.W. Fair enough. Lets talk about the day that Conceptual Metaphor Theory was born. G.L. We are in the seventies. Im a young professor, teaching at the Linguistics Department at the University of California at Berkeley. Its the spring semester and Im teaching a course on metaphors. Its early in the afternoon. Outside, its raining. We are in the San Francisco Bay Area, it rains all the time.The students have spent the week reading some text or other on metaphorsthat is, conventional metaphorsand we start class by discussing their reading notes. We are fifteen minutes into class when the door opens and a soaking wet student enters. She apologizes for being late, sits down, and opens her book. She seems distressed, and she is clearly struggling to hold herself together. But she doesnt say anything, and so we continue on with our discussion. Finally, its her turn to share her reading notes. She starts talking, but after the first few words she breaks into tears. We look up at her, alarmed and concerned. I ask her what the matter is and she replies, sobbing, Im having a metaphor problem with my boyfriend. Maybe you can help. He says that our relationship hit a dead end street. E.W. And so? G.L. Well, lets remember now, this is the seventies. Were in Berkeley, at the university that is the home of the Free Speech Movement. Were in the San Francisco Bay Area and Berkeley is at the epicenter of the cultural revolution of 1968. In short, we are living in extraordinary times.So, since we can tell that the student is going through a personal crisis, we embrace it, in the spirit of the time. We turn to a collective discussion of the crisis at hand.We are a good way into this therapeutic group discussion, when we say, Okay, look, your boyfriend says the relationship hit a dead end street. That means you cant keep going the way youre going. You may have to turn back. At this point, we realized that we were speaking of love in terms of travel. And we collected more and more examples: Its been a bumpy road, Were at a crossroads, and so on. And we realized that the metaphor was not in the words, it was part of the reasoning that lay behind all of the particular linguistic expressions. E.W. The young man didnt use a metaphor just to break the news to his soon-to-be ex-girlfriend in a rhetorically aesthetic manner. His underlying reasoning was in terms of that metaphor. G.L. Yes. In his mind a relationship was a vehicle that was supposed to help you go places in life, not take you to a dead end street. So when he felt that things were not going anywhere, he decided to get out . E.W. He used a very common metaphor, namely Love Is A Journey. Many people use this metaphor when making relationship decisions. G.L. And in his case, it meant ending a relationship that was stuck , that was not getting him anywhere. E.W. What became of your student? G.L. She is happily married, to another man. 1.2. Metaphoric Thought is Physical: How metaphors enter our brain E.W. Theres scientific evidence that we reason in terms of metaphors partly because of how our brains function. As we grow up, we automatically acquire a large number of so-called primary metaphors, without having consciously chosen any of them. G.L. Right. Take the More Is Up metaphor as an example. This metaphor is found throughout the world and across cultures. People speak of rising and falling prices. Stocks can go through the roof or be in the basement . Based on this metaphor, more is construed as higher up in space and less as lower down in space. And these mappings are asymmetric. We dont have the opposite mapping. We dont have a metaphor that construes more as down . We dont say, Property prices are at an all-time low to mean that property has become more expensive over the past years. E.W. But it is merely in our minds that prices rise . In reality, they do no such thing. They become more or less, a phenomenon of quantity, not verticality, but we perceive them as rising or falling because our minds automatically apply the More Is Up metaphor.The interesting question is, why, of all things, do we think about prices as moving around, up and down, and up again? Why do we use a metaphor that construes quantity in terms of verticality? G.L. The answer lies in our everyday experience. When you fill a glass with water, the more water you add, the higher the water level rises. When you put a stack of books on a table, the stack grows higher as you add more books to it. We all share this experience of seeing quantity correlate with verticality.Quantity and verticality are processed in different parts of the brain. Verticality is processed in a region that has to do with physical orientation in the world. Quantity is processed in a region that handles numbers and masses. The two areas are not even next to each other in the brain. Yet there are neural connections between them. E.W. Are we saying that all reasoning is metaphorical? G.L. No. Take the example of the water level that rises as we add more water to the glass. Well, that water level in fact rises . We can say, The water level has risen, and that is literal. That is not metaphoric. But when we say, The prices have risen, or Despite my diet my weight has not gone down , we are thinking and speaking in terms of a metaphor, a metaphor our brain acquired based on our experiences. E.W. The experiences we make as we live in this world result in physical changes to our brains. G.L. Yes. First off, all reasoning is physical. We understand the world via our brains, which are part of our bodies. Any reasoning process is always a physical process.And metaphors, for instance, are engrained in our brain just like all other things that structure human thought. The interesting question is, What determines the structural details of our brains? The answer is, in fact, To a large part, our experiences in the world.When we are born, there are a vast number of neural connections in our brains, connecting all sorts of neural clusters to each other. As we grow up between birth and the age of five or so, about half of those connections are lost. E.W. Hold on, that sounds as if our capacity to think is reduced by half in the first five years of our lives. G.L. Not at all. Our capacity to think is not being reduced. It is being formed. The right question to ask is not, How much can we think, but rather, In what way will we think?When we are born, we simply have this huge amount of random neural connections. Our brains are full of them. And as we grow older, half of them will be lost. And our world experience decides which connections we get to keep. Neural connections that get activated regularly through experiences during the first years of our lives get strengthened in the brain. E.W. And those connections that are not regularly activated get lost, because there is no experiential basis for strengthening them.The following picture emerges in my minds eye: our experiences are like an invisible hand that reaches into our brain, molding it. And we have no clue that this goes onits automatic. G.L. That is a good way to put it, yes. Our experiences structure the ways in which we reason. The more often we use any given synapse, the stronger a connection becomes, and the easier it is for the brain to activate the associated neurons.Now, when two areas of the brain are active at the same timelike in the case of verticality and quantity that we discussed just a minute agothose two regions grow strong synaptic connections. And via spreading activation along neural pathways linking those two regions, a neural circuit is formed. That circuit is the metaphor. E.W. In the cognitive sciences, this mechanism is called Hebbian learning. Experiential correlations lead to strong neural and cognitive connections. G.L. Yes. And so our cognitive apparatuses are heavily influenced by the experiences we make in our lives. 1.3. Metaphoric Thought is Inescapable: Not all arguments can be arguments E.W. The implications of these neural processes for our perception of reality seem quite drastic. It sounds like people are not free to think in whichever way they desire. Instead, it is the physiology of our brains that determines how we thinkand, moreover, what we simply cannot think! G.L. That is factually true. Lets revise the example of the More Is Up metaphor. We reason in terms of this metaphor because we see verticality and quantity co-occurring on a daily basis. And thus our brains acquire a neural connection between the two concepts. Once this has happened, we will automatically and frequently reason about quantity in terms of verticality, whether we intend to do so or not. We have no conscious choice about this at all. E.W. Every one of us automatically acquires a highly complex system of such conceptual metaphors. Some metaphors are simple in nature, like More Is Up . Others are complex in nature. G.L. Lets first consider simple metaphors. A good example of a simple metaphor is the Argument Is Physical Struggle metaphor: you can dominate an argument. You can be beaten in an argument. You can hit your interlocutor with strong points. We struggle over the outcome of an argument. E.W. Not so fast. An argument and a physical struggle de facto display a lot of parallels. To name just one, one person wins and the other person loses. Couldnt it be the case that we simply borrow language from the domain of fighting to have more vivid means of talking about arguments? G.L. Not really. We talk about arguments in terms of physical struggle because we automatically reason about them in this way. How do we acquire this metaphoric mapping? Well, as a child, we experience the two domains simultaneouslyover and over again. We argue with our parents and, at the same time, we struggle with them physically. Im sure you can recall situations like this one: your mom wants you to do a certain thing, say, not run across the road to play with another child. She holds your arm and says, No, stop, youre staying here. And while youre trying to shake her off, you lament, But I wanna go play!Now, this simultaneous experience of physical struggle and verbal argument results in the formation of the simple metaphor Argument Is Physical Struggle. E.W. People usually cite the Argument Is War mapping when it comes to metaphors for arguing. This construct has somewhat become a poster child for Conceptual Metaphor Theory. G.L. Yes, there is a metaphoric mapping that construes argument in terms of warfare. For instance, we talk about positioning ourselves in an argument and we battle with words! So yes, the metaphor Argument Is War is very real. But it is just one special case of the metaphor Argument Is Physical Struggle . E.W. Battling with words? Forgive me, but doesnt that seem a bit far-fetched. G.L. Not so. We all conceptualize words metaphorically as weapons. We speak of targeted comments. We aim at something with our words, we hit someone with words, even injure them. And Im sure you couldnt even put a number on how often you encouraged your students to speak by telling them, All right, shoot! E.W. Lets look at the complex metaphor Argument Is War more closely. Its composed of multiple parts. G.L. Yes. First of all, war itself is conceptualized metaphorically. In our reasoning, warfare between two nations is understood as physical struggle between two nations.Obviously, nations cannot actually physically fight each other. But when we think about nationhood, we commonly apply the metaphor Nations Are Persons . E.W. Nations talk to each other. They can be friends or foes . We speak of countries as our neighbor s, and so on. Those are just a handful of linguistic examples for the Nations Are Persons metaphor. G.L. And based on this metaphor, warfare is the physical struggle between two nation-persons. Now, add the metaphor Argument Is Physical Struggle and voilawe arrive at Argument Is War , with warfare standing in for one specific case of physical struggle. E.W. Why not skip all those steps and simply go with Argument Is , well, Argument ? G.L. People are free to try. But they shouldnt get their hopes up. Its literally impossible to avoid metaphor in our language and reasoning. We cannot disregard the physical realities of our brains. We simply cannot wake up one day and say, I will no longer reason in terms of metaphor, because metaphoric reasoning is automatic. In our brains, we struggle with each other as we argue. Thats the point. So, to return to your propositionno, we cannot simply think of argument as nothing more than argument, just as we cannot simply think of quantity as nothing more than quantity. We all share certain experiences as human beings in this world, and those experiences force our brains to acquire certain metaphoric mappings. E.W. Still, many people believe that things can be denoted in a literal way, just as they exist in the world, and that metaphor muddies the water in communication. John Locke once asserted: Metaphors must without question be entirely avoided in any discourse that claims to inform or teach the listener; whenever truth and knowledge are concerned, they ought to be considered a grave misstep, either of language itself or of the person that utilizes them. G.L. Notice Lockes metaphors. He metaphorically construes action as motion when saying its a misstep. And he metaphorically construes language as an instrument when saying a person utilizes it.Locke assumed that reality per se exists in the world, independent of our conceptual systems. He held that we could perceive things as they objectively exist, that we could speak and reason in purely literal terms.These assumptions about an objective reality are wrong. We perceive the world through a myriad of mental mechanisms, such as conceptual metaphors. We cannot understand things in this world in a disembodied, objective way. That thing we call reality is dependent not just on the nature of things in the world, but also the nature of our brains and bodies. We understand countless concepts via metaphoric mapping mechanisms developed by our brains over time. E.W. Reasoning about rather abstract ideas, for instance, is nearly impossible without metaphor. G.L. Right. Take the notion of affection. We refer to people who are generally kind to others as warm- hearted. We speak of someones cold heart. You can warm up to people you just met, and sometimes it takes a lot of time to get warm with someone. Relationships between people can cool off . And so on.As you can see, we process the somewhat abstract notion of affection via metaphor, namely, the Affection Is Warmth metaphor. E.W. And we do this because of experiences we make already as infants. Every time our parents held us in their arms, we experienced physical warmth and affection together. And so in our brains, the regions for computing temperature and emotion were repeatedly activated simultaneously. Our embodied mind has learned a connection between the two concepts, because they constantly co-occur in our experience. G.L. Right. And even though those regions are not even next to each other in our brains, we learned a neural connection between them through this recurring experience. This is far from being a rational choice, and we dont even notice this as it happens. It just happens. It is unavoidable. E.W. And the same goes for the metaphor Argument Is Physical Struggle . We dont consciously decide to reason about arguments in terms of physical fights. G.L. We certainly dont. We use this metaphor entirely automatically. Its part of our everyday unconscious reasoning. 1.4. Metaphoric Thought is Unconscious: Our minds very private contemplations E.W. You just said, Metaphor is part of our everyday unconscious reasoning. That statement is bound to raise eyebrows with more than a few of our readers, Everyday unconscious reasoning? Well, I dont know about you guys, but I know what I think! G.L. We have to disappoint those readers. Its safe to say that people do not know what they think most of the timeabout 98 percent of the time. That is, roughly, the percentage of human reasoning that remains unconscious to us. E.W. Unconscious thought in a Freudian sense would imply that we couldnt ever access those parts of our reasoning. How can metaphoric mappings guide our everyday perception of the world if we are not even able to access them? G.L. Unconscious thought as the cognitive sciences define it has nothing to do with Freuds notion of the unconscious. In cognitive science, the unconscious mind simply denotes all the parts of our reasoning that we dont notice, dont reflect upon, and cannot control. E.W. One would think we need insight into our own thoughts in order to keep them clear and in order. How can we grasp our own ideas if were not fully conscious of them? G.L. The right question to ask is, How could we ever manage to understand all the mental and neural mechanisms that guide our thoughts?You just asked me how we could grasp ideas without being aware of their mental structure.As you posed that question, did you consciously reflect upon the fact that you were using the Ideas Are Objects metaphor? That by grasping ideas you become a metaphoric agent that handles ideas as metaphoric objects. Were you aware that we use this metaphor when we call some ideas easy to grasp , when we speak of exchanging ideas, or when we bury bad ideas?Did you consciously think about the fact that ideas may also be understood in terms of other metaphors, such as Ideas Are Food a metaphor that guides expressions, such as chewing hard on ideas, swallowing ideas, digesting ideas, or giving feed back?Or did you consciously consider using yet another metaphor, such as Ideas Are Locations ? This metaphor guides expressions such as jumping from one idea to another, arriving at good ideas, distancing oneself from bad ideas, and approaching solutions.Did you deliberately ponder all of those options? I dont think so. We would have had to wait for a long time for you to formulate your question! E.W. But if people were to invest that time, technically, they could arrive at a conscious understanding of the conceptual mechanisms they usually remain unaware of. After all, this is what we do in cognitive science research, which studies the unconscious part of human everyday cognition and language. G.L. Sure. You can analyze the complex system of concepts and mechanisms behind peoples communication, decision-making, and general perception of reality, which is what cognitive science research doesand we begin to understand that complex system more and more. 1.5. Metaphors Dont Come Alone: The many different ways to reason about things E.W. We just discussed a number of different metaphors we commonly use when reasoning about our own reasoning. Ergo, we can have multiple metaphoric mappings for one and the same idea, for one and the same object, action, feeling, or whatever else. G.L. We can indeed, because there are manifold experiences that correlate with each other. As an example, lets consider the notion of purposeful action, metaphorically speaking: the type of action that gets you to where you want to be or gets you the things you want to have . E.W. When we use the first metaphor, we construe the purposes of our actions as geographic destinations and our actions as movement towards such destinations. This is called the Purposes Are Destinations metaphor. Now, the interesting question is, why do we use this metaphor? G.L. Well, we all know what its like to want to get from one location to another, from a starting point to a destination. Say you are a child, and you want your blanket, which is in the kitchen. To get your blanket, you have to go to the kitchen. Once you arrive at the kitchen, the purpose of your action has been fulfilled ormetaphorically speakingyour goal has been reached . Every day there are purposes that can only be fulfilled by moving towards a destination. This is how we acquire the metaphor. And this experience of moving towards a destination with purpose gets generalized and applied to all kinds of purposeful action. We say, I reached my career goals , and mean by that: the purpose of my actions has been fulfilled. E.W. A whole set of expressions falls out of this mapping: I have not yet arrived at my goals. I took many detours before getting to my goal. I overcame many hurdles in my career. I had to get around many obstacles on my way to the top. I reoriented myself towards a more balanced lifestyle. I got ahead in life. And so on.But we said there are two metaphoric mappings for purposeful action. What about the second one? Why do we think and talk about the goals of our actions as objects? G.L. We all share the experience of wanting an object. Lets say you are a child and you want your teddy bear, which is sitting on a shelf. Your demonstrably point to the bear so your parents will notice. Maybe you cry, whatever it takes. And then, once you hold the teddy bear in your arms, the purpose of your actionspointing and cryingis fulfilled. Your brain learns a mapping between purposeful action and object acquisition. This is why we say things like, I got what I wanted in life, to express that the purpose of our action has been fulfilled. We can pocket a success. We can reach high in life, and sometimes our goals are far-fetched . We can lose our grip on things, and we can make the wrong decisions and thereby throw away our career or marriage.Bottom line, one and the same thing can be reasoned about in terms of two or more different metaphoric mappings. That is very common. E.W. Right. Love, for instance, is an abstract concept that plays a huge role in our lives. Think of all the decisions that are being made around the world based on how we reason about lovewhether they turn out to be the right or the wrong decisions, they are largely dependent on the metaphors that people resort to in order to reason about love.Love has many different metaphors. There is love as a journey towards shared life goals. There is love as a partnership with shared burdens and gains. There is love as becoming one unit . There is love as an invisible power that functions as a connection between two people. There is love as heat , which is why we sometimes speak of love having grown cold . And so on. All these metaphors have different experiential bases in our lives. G.L. And some of those metaphors seem to be shared across many cultures, while others are not. 1.6. The Cultural Brain: Why humans cannot all think alike E.W. Youre making an important point. Not all metaphoric mappings are shared by all humans. G.L. Exactly. Only those metaphors are shared across many cultures that we learn on the basis of how the human body functions in the world, that is, what all our bodies have in common in terms of how they function in the world. Anger Is Heat, for instance, is learned by all humans. We all share the basic experience of our body temperature rising, as we get angry. The feeling of anger and the increase in body temperature correlate, the two relevant brain regions are activated at the same time, and the neural connection gets strengthenedvoila! E.W. But this fundamental, largely culture-independent mechanism is not true for all metaphors. People grow up in different cultures, and they gain different cultural and subcultural experiences. And thus they learn different metaphors. Societal experiences can impact metaphor acquisition quite strongly. G.L. Right, this is true for love, for instance. Different cultures have different mappings for this concept. Lets take Love Is A Journey . This is a complex metaphor that rests on a couple of smaller mappings. For instance, a relationship is understood as a vehicle. That mapping is omnipresent in language. Their marriage has run aground : the relationship as a boat. Their marriage has derailed : a train. Their marriage is spinning its wheels : a car. Why this mapping? Because a vehicle is something we use to move from one place to another. Thus, if you have shared life goals, you can jointly move towards them in the relationship vehicle. And notice that another mapping is relevant here, namely, Life Purposes Are Geographical Destinations . If you take those two elements together, you start to see why we speak of relationship difficulties as difficulties in movement: a couple can overcome obstacles and find their way together, and others divorce because they find theyre going in opposite directions . E.W. So when people start relationships with each other, what they really do, cognitively speaking, is get into a car, board a train, or get aboard a ship. G.L. No doubt. And some might even board a space shuttle, a submarine, a hot-air balloon, or a gondola. The metaphor Relationship As Vehicle is ubiquitous. Its not the only metaphor for relationships, but it is highly common in many cultures. E.W. But why a vehicle, one might ask. Why cant we just move towards common life goals by foot? G.L. There are a couple of reasons. First, a vehicle is a container. And relationships are commonly metaphorically processed as containers. We get into a new relationship, we stay in relationships, and we get out of relationships. The metaphor Relationship As Container is a very basic one. And vehiclesas a type of containernaturally match this construct.Second, vehicles are containers with confined space, where passengers are physically close to each other. Well, Intimacy Is Closeness is one of our core mappings when it comes to reasoning about human relationships. People in a relationship can be close , they may drift apart , and they may distance themselves from each other. E.W. So if a friend says, My girlfriend and I have never been as close as after her accident last year, then he uses the Intimacy Is Closeness metaphor. He does not mean to say that they never sat closer to each other on the couch when watching TV, and he does not mean to say they never slept closer to each other in their bed. What he is saying is that they never were more intimately connected to each other. G.L. Right. Now, why do we have this mapping? Because, when we are children, we learn that people we intimately know are also physically close to us. Our parents hold us in their arms. Our siblings share a room with us. The whole family lives in one house. These are the types of experiences that result in the Intimacy Is Closeness metaphor.Now, all these metaphoric elements come together in the complex metaphor Love Is A Journey : a relationship is a vehicle where two people sit close to each other and move towards shared life goals together. E.W. If Love Is A Journey is not exclusively grounded in direct physical experiences, then there should be people who do not know this metaphor at all, people who are not able to reason in terms of this metaphor even if they wanted to. G.L. Thats right. There are in fact people who arent familiar with the metaphor Love Is A Journey , for the following reason. In order tometaphoricallymove towards life goals together, you first need the notion of having such things as life goals. And while this may be surprising for some people, we know of cultures that do not construe the meaning of life as pursuing and reaching goals. And, in those cultures, there simply are no foundations for acquiring a metaphoric mapping along the lines of love as a journey towards shared life goals . E.W. And thats not the only reason why some people dont develop this mapping. There are cultures in which women are extremely subordinated to men, and in those cultures a metaphor that construes love as a journey towards a shared life goal doesnt fly, for obvious reasons: only the husbands get to make decisions about life goals. The wife merely follows along. In this cultural context, a metaphor that construes love as a journey towards shared life goals is nonsense. G.L. No doubt about it. So, bottom line, societal experiences can strongly impact which metaphors will become the conceptual foundations of our everyday livesand which metaphors will be inaccessible to us. And if we have cultural differences in metaphor, we probably have culture-dependent differences in brain structure. 1.7. The Secret Selectors: How metaphors determine what we dont think E.W. Lets talk about how metaphoric cognition impacts our perception of things in detail. G.L. Have you ever been to Athens? E.W. Yes. G.L. Did you take a close look at the busses they have there? E.W. Busses, as in public transport? G.L. Yes. E.W. No. G.L. Aha. Let me tell you, then, what is written across busses in Athens, metaphoroi. The word metaphor stems from Greek and literally means, to carry things to another place. Metaphoric cognition, thus, means that we resort to elements from one cognitive domaincommonly one that we can directly experience in the worldin order to reason about another cognitive domaincommonly one that is more abstract. E.W. In cognitive linguistics, the two are labeled source domain and target domain. Semantic elements and relational structures from the source domain are being mapped onto the target domain. And this conceptual process is called metaphoric mapping. Its important to point out, though, that not all elements from one given source domain are being mapped onto the target domain. G.L. Right, because if all elements were mapped from one domain to the other, we would no longer be looking at two conceptual domains, but merely at one concept! Metaphoric mappings are not exhaustive in the sense that all elements and relational structures are mapped from domain A to domain B. E.W. And this is one of the most interesting and intriguing things about metaphors: they have a restrictive component to them. G.L. Yes. Whenever we use one given metaphor in our language and reasoninginstead of using, say, another available metaphor or non-metaphoric structureswe restrict our understanding of the target domain to the structures that are provided by the source domain. And at the same time, the structure provided by the source domain profiles certain aspects of the target domain. Thus, metaphors both hide and highlight things that are inherent to the target domain. E.W. This selective nature of metaphoric cognition has considerable implications for our perception of reality. G.L. Exactly, because the metaphors we use determine what aspects of any given issue we will focus onand what aspects our minds will simply ignore. 1.8. We Do as We Think: Acting out metaphors E.W. A moment ago, we said that metaphors are a matter of thought, language, and action . How about an example for the ways in which metaphors influence joint societal action? G.L. Lets take the concept of morality. Morality is an essential driving force in politics. On top of that, morality is an abstract concept, a concept that our minds naturally and unconsciously process in terms of metaphoric mappings.There are quite a few different metaphors for morality. One way to reason about morality is in terms of the Moral Accounting metaphor. This metaphor builds on our experiences with well-being. By the way, this is a general phenomenon. All our metaphoric reasoning about morality is grounded in experiences with well-being, in the following way: things that maximize well-being are good or moral; things that minimize our well-being are bad or immoral.Now, lets look at the origin of the Moral Accounting metaphor. Our experience in life is that we are better off when we have the things we need. We thus have the metaphor Well-Being Is Wealth . And when you combine this general metaphor with the notion of accounting, you arrive at metaphoric moral accounting, in the following sense: maximizing well-being through moral action is conceptualized as an increase in wealth, and minimizing well-being through immoral action is conceptualized as a decrease in wealth. E.W. That reasoning underlies many of our everyday expressions. If someone has done us a favor, we give a favor back later on. Until we do so, we have a moral debt . We owe that person a favor. And so on. Now, the crucial thing is that we do not just reason and talk about morality in this way, but also act based on the metaphor. But what if the opposite happens and instead of doing favors for each other, people harm each other? G.L. Okay, now this is interesting. There are different ways in which people may reason and talk about harm, and then act accordingly. For one, a person that did something bad can balance the books by doing something good in return. Thus, theres a concept of moral restitution, a notion that immoral deeds can be balanced via moral reparation : when you did something bad, do something good that weighs in at about the same level, and moral order is restored.But there is also another inference that emerges from the Moral Accounting metaphor. That inference leaves us with quite a different story, and here is how that story goes: a person that did something bad receives a payback from the others. Harm is inflicted on the wrongdoer to compensate for the harm he or she has done, and this balances the moral books. This is the concept of moral retribution. And then theres revenge, which is more complex. It uses a form of moral arithmetic in which taking something good away from people is the equivalent of doing something bad to them. This is a metaphorical version of literal accounting, in which removing a credit is imposing a debit. This is how revenge cultures work. E.W. In other words, if someone takes a piece of yourwell-being, you have two options. You can have that person restore yourwell-being by doing something good for you. Or, you can take a piece of their well-being by doing something bad to them. G.L. Yes. And in both cases we balance the books , or get even . Which is understood as a form of justice. E.W. And if we fail to do so we are left with a debt to settle. G.L. Exactly. As you see, the ways in which we reason about morality are entirely dependent on metaphor. When people deal with moral issues, they commonly use the Moral Accounting metaphor. Whether they follow the concept of restitution or the notion of retribution, the books must be balanced. Immoral deeds must be paid for in one way or another. 1.9. The Public Brain: Metaphors in political discourse E.W. We already talked about the selective mechanism of metaphors, the fact that they both hide and highlight realities. The implications of this for political reasoning are huge: metaphors used in public discourse can determine what people thinkand what they ignore! G.L. Right. All the things in the world that we reason about actions, objects, emotions, policy issues, and so oncan be construed in terms of not just one, but many different source domains. However, those different source domains are never used simultaneously. Rather, our minds have to choose one of them. E.W. And here is where it gets interesting: this choice is usually entirely unconscious. Its simply not the case that we look at abstract concepts, such as taxation, and ask ourselves, What source domain for taxation should I use today? G.L. Right, but if the choice is not conscious and deliberate, then how is that choice being made? Well, to a great extent, its the language that is used in public discourse that determines how things are perceived. Metaphoric language evokes metaphoric structures in our minds, and those structures will guide our understanding of a given thing or situation. E.W. And since different metaphoric source domains will always both highlight and hide different aspects of the thing we reason about, metaphoric language has a huge impact on our perception of realityboth in everyday life and in politics. G.L. But thats only one part of the issue. There is more to this. Namely, the more often a metaphoric mapping is used in language, the more that metaphor is being engrained in peoples brains due to synaptic strengthening.If public political debate implements one given metaphor again and againthen that metaphor becomes our primary way of perceiving the issue at hand. The mapping simply becomes part of our common sense, our only, unquestionable, and inherently rightful shared understanding of the issue. E.W. This is, obviously, problematic because alternative perspectives of the issue at hand are not just momentarily ignored but, moreover, not cognitively maintained and strengthened as part of our conceptual apparatus. G.L. Exactly. And this is part of the power of metaphor in political language and reasoning. The metaphors that dominate a discourse will greatly determine how both the speaker and the listener think, and what they do not think, which is anything that the prevalent metaphoric mapping hides due to the nature of its source domain. E.W. That sounds a tad unnerving. Couldnt people decide to reject the metaphors that public discourse offers them and choose to think about issues in terms of alternative mappings, ones that highlight whatever aspects of a situation are important to them ? G.L. Theoretically, yes. To a certain degree, political actors and parties can indeed be masters of their own fate when it comes to metaphor and politics. Language and discourses can be analyzed for predominant metaphoric mappings and their effects on our perception of the issue at hand, whether it is taxation, welfare, or the environment. Metaphors that seem to contradict ones understanding of an issue can be disregarded, while metaphors that are in line with ones ideas can be given priority in ones communication. And so on.But our readers shouldnt get too excited at this prospect. Because the reality is that people very commonly do not do any such thing, whether they are involved in social and political action or merely citizens in a democratic society. People do not question the metaphoric structures that public debates and policy decisions are rooted inusually they dont even know that they are speaking, thinking, and acting in terms of metaphors. E.W. Because many people, entire nations even, hold outdated beliefs about human reason. People say to themselves, I know what I think, and I perceive things as they objectively exist in this world. And not only that, I can also talk about them as they exist, in a literal sense, without any such thing as metaphor. G.L. And you know what? This is exactly why metaphoric language is so effectiveand potentially dangerousin political public debate. E.W. Because metaphors can create political realities in our minds and we dont even notice it. G.L. And this is not least due to the fact that we are oblivious to the workings of our own reasoning.Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

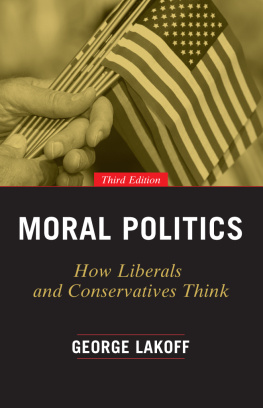

Similar books «Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide»

Look at similar books to Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Your Brains Politics: How the Science of Mind Explains the Political Divide and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.