Contents

Guide

Page List

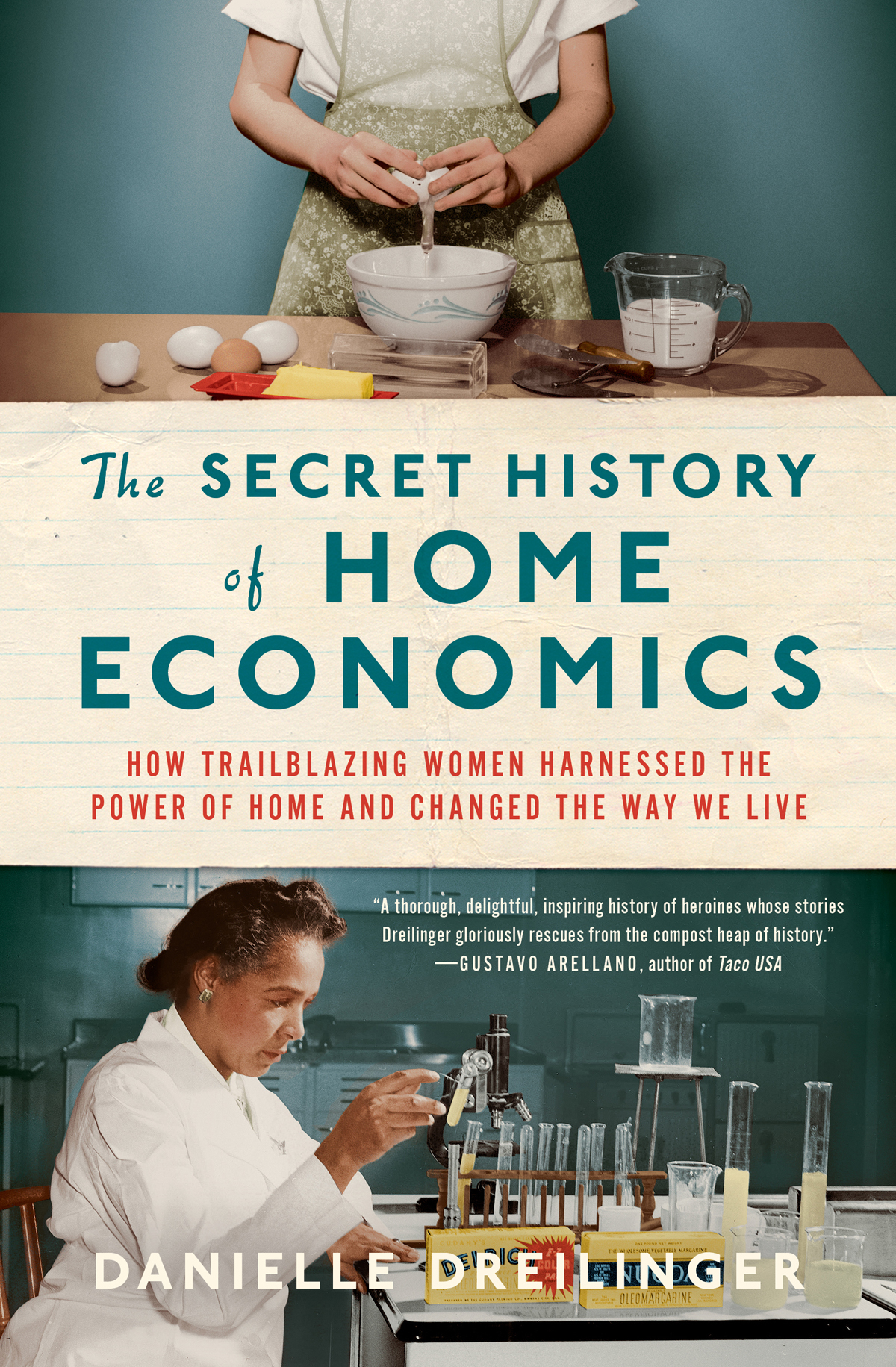

THE SECRET HISTORY

of

HOME ECONOMICS

How Trailblazing Women

Harnessed the Power of Home and Changed

the Way We Live

DANIELLE DREILINGER

This is for Kate.

CONTENTS

W hen you imagine the founder of home economics, who do you see? Betty Crocker, Donna Reed? A white man with a handlebar moustache glaring at women to stay in their place? A stern, conservative lady teacher with 1950s glasses, teaching girls how to do houseworksomeone like Dolores Umbridge, only less evil?

Try a white female chemist, Ellen Swallow Richards, the first woman to attend MIT, who believed fervently in the power of science to free women from drudgery. My life is to be one of active fighting, she wrote. Try a famous Black woman, Margaret Murray Washington, who thought that improving the home could end racial inequality.

Thats all you need to know to realize that everything you thought about home economics is wrong. Home economics was far more than baking lumpy blueberry muffins, sewing throw pillows, or lugging a bag of flour around in a baby sling to learn the perils of parenting. In its purest form, home economics was about changing the world through the household.

Home economists instructed and inspired waves of women who built science careers helping people live better lives. Together, they built an empire of jobs and influence. They originated the food groups, the federal poverty level, the consumer-protection movement, clothing care labels, school lunch, the discipline of womens studies, and the Rice Krispies Treat. They were the first to measure the economic value of housework and the amount of physical effort it took. They enabled millions of people around the world to survive harrowing deprivation. They had the ear of presidents and first ladies and queens. They helped win wars. Their work operated in as large a sphere as battlefields and on as intimate a scale as counting calories. All done with pragmatic empiricism, with an eye on careers. Home economists created tens of thousands of jobsnot just in high school classrooms but in labs, colleges, government agencies, and business departments. For decades, there was always a job for a home economist. For decades, the profession was even respected.

Through home economics, Gladys Gary Vaughn went from segregated Florida to a doctoral degree and a career that included the civil rights office of the US Department of Agriculture and the presidency of a major international volunteer organization. The nation has benefited. They have laughed at it. But they have benefited, she said.

Home economics has been a back door for women to enter science; part of a surprisingly large government-backed movement; a guilt trip for women left cold by the household arts; a trapdoor or a springboard for women of color; a sometimes ironic, sometimes nostalgic preoccupation of third-wave feminists; a conservative calling card; an aesthetic obsession for the Instagram set; a feminist battlefield; and the locus for countless anxieties about womens lives.

A revival seems bewilderingly overdue. The last twenty years have seen countless DIY homemaking blogs, the Food Network and Project Runway, Instagram and Pinterest, eco-friendly slow fashion and knitted pussyhats. We live amid high-pressure parenting, financial and environmental crises, the return of vo-tech education, stress over adulting, and women still doing the lions share of home labor. In response to a global pandemic, people stripped supermarkets of flour and big-box stores of sewing machines. Why hasnt home economics come back? Practitioners will tell you: because it never went away. Though most people think it went the way of the eight-track, home economics is, though diminished, still here.

I went to the 2019 convention of the national family and consumer sciences associationthats what the field calls home ec nowand saw its members address crucial societal problems with creativity and compassion. A fifty-year-old father, veteran, and prison educator presented his dissertation on how he used self-exploration to gain insights into reducing the chances of prisoners reoffending after release. A fashion student manufactured bags from an upholstery factorys leftovers. A teacher at a Native American boarding school told me about the day each year that she takes the students to fish and then to clean and cook their catch. (Its a very long day.) She hoped her lessons would give them an alternative to the few options in their remote communities besides fast food. A St. Louis housing inspector went back to school for home economics and thought she would change jobs after graduation, only to realize that her new studies fit perfectly into her current job. Now she brings neighborhoods together around reducing blight. And yes, an Idaho community educator talked to a full room about her Instant Pot workshops. Many people who attend get multicookers as presents and then dont use them because theyre scared of blowing something up, she said. That session took on extra significance when I visited my mother and we took her new Instant Pot out of the box where it had sat since the holidays.

But, you argue, we cant fix the world one person at a time. Making ones own clothes is an expensive privilege when shirts are cheap at Walmart. Cooking dinner doesnt solve health or family problems, and emphasizing the value of home cooking puts an unnecessary moral burden on people who are already struggling to raise children without enough time or support. Women are still stuck trying to do it all, while we still dont expect the same of men. Youre not the first to air those arguments. Home economists have made all these points, the exact same ones, over and over again. Their foresight has been tremendous. To thumb through the home economics literature is to find our current questions debated decades or longer ago. In 1899 home economists argued for school gardens, STEM education for girls, takeout food, and affordable day care. Forty years ago, under visionary businesswoman Satenig St. Marie, J. C. Penneys home economics magazineyes, one existed, and its fascinating, as youll seeaddressed conscious consumption, the impact of screens on children, and racist microaggressions. And yet home economics has been denigrated, over and over and over again, as just stitching and stirring.

Sewing is actually a perfect example of the fields sophistication. Its place in home economics has been stereotyped, omnipresentand eternally questioned. The sewing machine, patented in the US in 1846, was a truly revolutionary invention. Nonetheless, Richards and Washington didnt find sewing romantic or soothing, living as they did in the time of textile factory accidents and women taking in piecework to try to keep their families from starving. Even when home sewing appeared to be cheaper than buying, home economists reminded everyone that womens time had value. Simultaneously, they sought to protect garment workers and customers by fighting for better working conditions, nonpoisonous dyes, and accurate labeling of consumer goods. Mass production, they believed, should not free some women from drudgery by exploiting others. Moreover, many home economics teachers insisted that sewing instruction should cohere with intellectual goals, should be carefully designed to lead to real careers and exercise the brain as much as the fingers. Skill of hand may but multiply our cushions and doilies, a Massachusetts home economics teacher wrote in 1917. Power of intellect will go further. A college administrator forty years ago advocated to replace sewing machines with chemistry equipment and study fibers for their endurance and thermal properties; and then study the subsequent fabrics for safety and comfort features for persons of all ages and for consumer aspects of durability. Virginia teacher Angela DeHart carried on that tradition in 2017: she got rid of her classrooms sewing machines, because the only jobs they prepared students for were sweatshops outside the country. Hand-sewing was a different matter, however, and she did teach that: surgeons, she said, have to sew. Yet despite decades of pushback, machine-sewing has endured in home economics. Students and teachers told me that sewing taught spatial relations, geometry, and problem-solving, and helped with stress relief and depression. To everyones surprise, the coronavirus pandemic even revived its utility, as people clamored for masks.