Contents

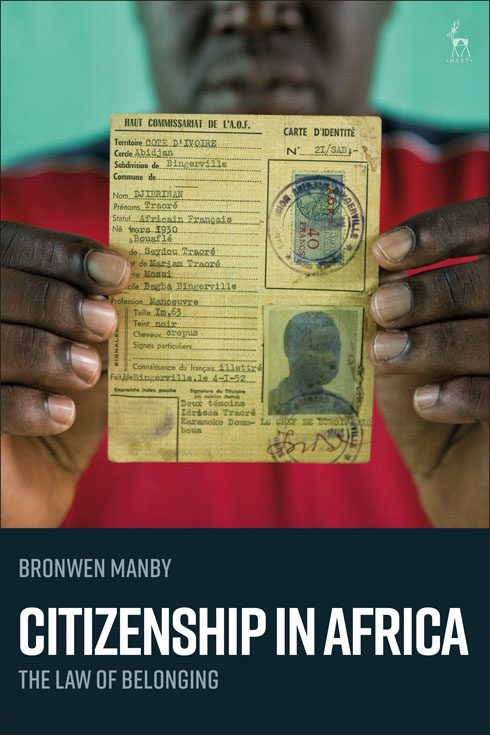

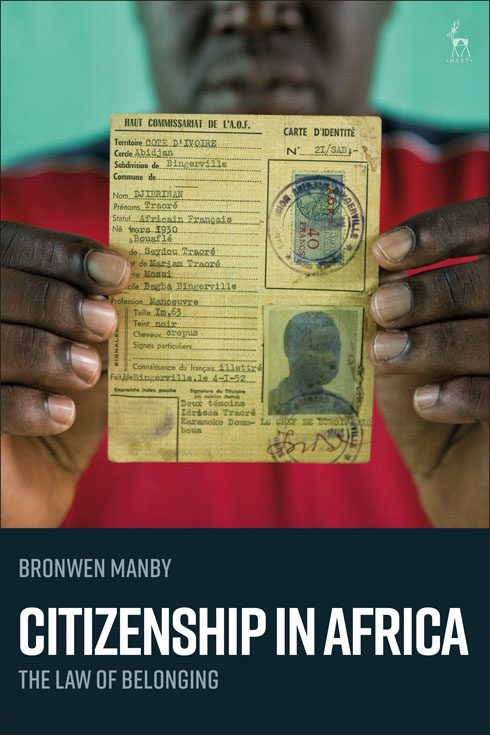

CITIZENSHIP IN AFRICA: THE LAW OF BELONGING

Citizenship in Africa provides a comprehensive exploration of nationality laws in Africa, placing them in their theoretical and historical context. It offers the first serious attempt to analyse the impact of nationality law on politics and society in different African states from a trans-continental comparative perspective. Taking a four-part approach, explores the impact of the law on politics, and its relevance for questions of identity and belonging today, concluding with a set of issues for further research. Ambitious in scope and compelling in analysis, this is an important new work on citizenship in Africa.

Citizenship in Africa:

The Law of Belonging

Bronwen Manby

First I must thank Professor Ren de Groot of Maastricht University for suggesting the doctorate that forms the basis of this book, and for taking on the role of my supervisor. Thanks are also due to my PhD examination committee, especially Maarten Vink of Maastricht University and Rainer Baubck of the European University Institute, who provided additional and very helpful comments on the concluding chapters; as did Mike McGovern of the University of Michigan (with even less obligation to do so). The anonymous reviewers who provided feedback on the book proposal also gave invaluable advice.

The thesis itself drew on the publications and reports I had previously written on the right to a nationality in Africa, many of them listed in the bibliography. Much of this research was conducted on behalf of the Open Society Foundations and UNHCR. I should like to emphasise also my debts to Chidi Odinkalu and Ibrahima Kane, who have informed my thinking on these issues over many years and have been inspirational leaders and colleagues in advocacy efforts on the continent. Pascal Kambale was an early sounding-board on the political complexities of the Democratic Republic of Congo; while Mirna Adjami gave generously of her time to comment on the intricacies of the law in Cte dIvoire. I have benefited greatly from visiting fellowships at the Centre for the Study of Human Rights at the London School of Economics, from working with UNHCRs Statelessness section in Geneva and staff in the field, and above all from ongoing discussions with as the community of scholars and activists working on statelessness in different countries around the world with whom I have had the privilege of interacting.

Finally, thanks to Robert Cohen, whose support throughout the years I have been researching and writing on these issues has been the foundation of everything.

ACHPR | African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights |

ACERWC | African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child |

ACRWC | African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child |

AEF | Afrique quatoriale franaise (French Equatorial Africa) |

AOF | Afrique occidentale franaise (French West Africa) |

AU | African Union |

CEDAW | Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women |

CERD | Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination |

CPA | Comprehensive Peace Agreement (Sudan) |

CRC | Convention on the Rights of the Child |

DRC | Democratic Republic of Congo |

EAC | East African Community |

ECOWAS | Economic Community of West African States |

EU | European Union |

ICCPR | International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

ICJ | International Court of Justice |

IOM | International Organisation for Migration |

IRIN | Integrated Regional Information Networks (formerly of the UN) |

OAU | Organisation of African Unity |

PALOP | Pases Africanos de Lngua Oficial Portuguesa (African countries with Portuguese as the Official Language |

PCA | Permanent Court of Arbitration |

PCIJ | Permanent Court of International Justice |

SADC | Southern African Development Community |

SPLA/M | Sudan Peoples Liberation Army/Movement |

UK | United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) |

UN | United Nations |

UNHCR | UN High Commissioner for Refugees |

UNICEF | UN Childrens Fund |

A child born in Kailahun district of north east Sierra Leone as a member of the Kissi people is likely to have extended family across three countries. The district forms a promontory of territory between Liberia and Guinea; an anomaly created by the classic ruthless division of existing socio-political units by colonial borders.

Each of the three countries has entirely different formal legal traditions, and entirely different rules on who qualifies for its nationality. Let us say that our Sierra Leonean child, well call him Samson, does well in school, and wishes to go and study in Freetown on a government scholarship. To qualify for the scholarship, he will need confirmation that he is Sierra Leonean. The rules applied in Sierra Leone under the 1973 Citizenship Act are that a person is a citizen if born in Sierra Leone of one parent also born there, provided the parent is of negro African descent. Samson has a cousin in Guinea, well call him Georges. Georges wants to study in Conakry, and to get the equivalent scholarship he has to fulfil the requirements on nationality set out in the 1983 civil code, and show either that he has a Guinean parent, or that he was born in Guinea and has remained resident there until he turned 18. The third cousin, Lisa, was born in Sierra Leone, but moved to Liberia when very small with her mother, who was herself born there, and she has grown up in Liberia. Liberian law contradicts itself: the constitution says that the child of a Liberian mother or father obtains Liberian citizenship at birth; but the Citizenship and Aliens Act of 1973 says that citizenship is acquired automatically based on birth in Liberia, while women cannot transmit citizenship to their children born outside Liberia. Only negroes are eligible for Liberian citizenship.

One ethnic group, three countries, three entirely different citizenship regimes; or three and a half, if Liberias contradictions are taken into account. Add to these complications the fact that birth registration, the primary route established in law to prove a childs origins, is only around 5 per cent in Liberia, and well under 50 per cent in Guinea, though almost 80 per cent in Sierra Leone. Guinea has had a requirement to carry a national identity card since independence, but in practice less than half the adult population is estimated to hold one. Sierra Leone and Liberia only began the process of introducing national identity cards from around 2015. In Guinea, a magistrate has the power to confirm whether or not Georges is Guinean by birth; in Liberia and Sierra Leone, however, the executive branch is in complete control of the process of determining if a person is a citizen.