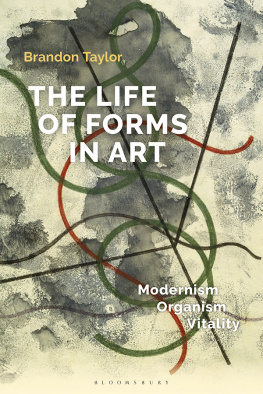

The Life of Forms in Art

The Life of Forms in Art

modernism, organism, vitality

Brandon Taylor

Plates

Figures

What is form? Or rather: What was form to a generation of European artists coming to activity after the end of the First World War and the onset of the 1920s? How would the artist explore the fashioning of line, mass, volume and scale, now disburdened of the obligation to copy the appearances of natural and physical things? Part of the answer would arise from the very conditions of European life. In war, in industry and in the workplace mechanization, time-keeping and control. In urban life, increasingly utility, efficiency and the plan. A technical modernity, in other words, in which all fields of enterprise and inquiry were potentially caught up. Yet it was one in which the technological embrace was not everywhere welcome. Questions were arising had already arisen prompted by an impulse to happenstance and experiential flow, to be cognizant of variation and chance, of absurdity and the dream. A certain tension between extremes, therefore: between rational order and the irrational; between measure and motion, data and rhythm; between the what and the how of consumption. By what means could clock-time, chronicity, management the modernity of quantification be reconciled with subjective experiences of sensation and cognition? Could the artwork itself come to embody the temporalities of change, transformation and decay? Such questions would crop up repeatedly in the practice of art in the decades between 1920 and 1950. They defined the troubled consciousness of an era, and we have the artworks of the period to demonstrate variously how.

My broad proposal to anticipate a theme that will run through most of what follows is that such questions proved inseparable from certain apprehensions about the definition of life itself. In the studios and in conversation, the languages of artistic practice were changing fast as the First World War came to its grisly end. To mention one significant symptom: for most artists, Cubism was already behind them. A compositional device consisting of taut straight lines that divided planes sharply from each other, or provided facets with edges and direction, or provided offered metaphors for machinery and the efficient use of space: that device was already giving way to the wandering line, to curvature and to organic form, so-called to a semblance of association with nature, even with the biological.

Few could fail to be struck, for instance, at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, by the growth of scientific explanation in a world once assumed to be organized by the deity. And yet an intractable question was implied thereby. How could the wellsprings of natural, animal and human growth be accounted for in a universe increasingly understandable as mechanism, be it from physics, physics combined with chemistry, or from chemistry alone? The answer provided by Darwins The Origin of Species of 1859, that life was perpetuated by nature working blindly by chance mutation and adaptation appeared to drain quality itself from the quantitative workings of a vast machine. Even more troubling: if life was not superintended by the deity, and if the arrangement of living things was governed by nothing other than random mutation and selection, then life and non-life might be merely a continuum, with no essential differences between them. An alternative course would be to ask questions about concepts of organization, generation, growth and decay that traditional theology and metaphysics had been unable to answer. By the later decades of the nineteenth century, it was clear too that observations from the laboratory were inescapably philosophical, hence metaphysical and even ontological; that data from the laboratory would need to support, if not entirely answer, fundamental questions about the differences between living and non-living things, between organic and inorganic substance, and about categories, consciousness, agency, even the experience of time itself.

A particular term vitalism had since Aristotle been used to define the distinction between living and non-living things by reference to a quality called entelechy, an immaterial power or property that animated any entity that could be regarded as a living whole. Since the rise of observational science in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, vitalism had fallen into disrepute; but in the wake of Darwin some more critical versions had started to take hold. The experiments on the sea-urchin embryo by the German biologist-philosopher Hans Driesch, for example, first published in the 1880s and then presented in his Philosophie des Organischen [Philosophy of the Organic] of 1909, consisted of waiting for the single-cell embryo to divide by itself, then separating the two resulting cells and watching them multiply into four-celled, then eight-celled (etc.) organisms up to a maximum of about 800 cells. To Driesch, the experiment was enough to suggest that life was sui generis, inasmuch as separation of a single cell from the component body prompted organic regulation; that is, the normal functioning of each separated part as an independent whole. To Driesch, the organism could be described as possessing a novel form of entelechy consisting of equi-potentiality, which assigns a similar growth potential to each separated embryo cell, and secondly equi-finality, designating a common growth destination for them all. Here, it appeared, was a non-physical account of the growth and decay of living entities organisms that was neither mechanistic nor reducible to mechanism, nor to the versions of late nineteenth-century positivism that gave mechanism its support. On the contrary, growth and vitality seemed non-mechanistic attributes of any organism in its evolving and changing form; in which case organicity, the quality essential to any organism, might be immanent in the universe. We shall see how, for many artists grappling with the demands of the new century, organicity might even function as a model for the work of art.

To Drieschs proposals were soon added other announcements that placed in doubt the distinction between living and inert matter. The physicist and microscopist Otto Lehmann of the University of Karlsruhe observed the internal changes of crystals under conditions of varying temperature and pressure, describing them as liquid [flssige] or flowing [fliessende] crystals in his books Die Kristallanalyse [The Analysis of Crystals] of 1891 and Flssige Kristalle [Liquid Crystals], 1904 or sometimes rheocrystals in acknowledgement of Heraclitus maxims on universal flux. The photographs published in Lehmanns next book Die Neue Welt der flssigen Kristalle [The New World of Flowing Crystals] of 1911 purported to show animated web-like or mucoid forms, even snake-like filaments, multiplying and branching as if alive. The bio-philosopher Ernst Haeckel, who had taught Driesch at the University of Jena in the 1880s and who in the 1860s had published pictures of tiny living animals known as radiolaria that had seemingly perfect and intricate symmetry, now issued his own account of the living qualities of matter, first in his popular Kunstformen der Natur [Artforms of Nature] of 1904 and then, following Lehmanns books on crystals, in the philosophically more ambitious Kristallseelen: Studien ber das anorganische Leben [Crystal Souls: Studies in Inorganic Life] of 1917, in which he was prepared to say that evidence from the internal movements of crystals was such as to suggest the presence in them of sensation, feeling, temperament even real life [

Next page