Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

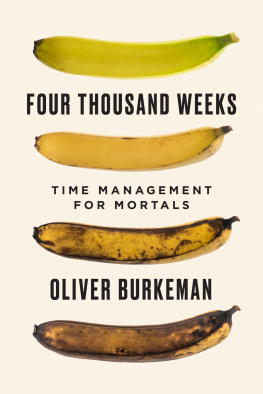

ALSO BY OLIVER BURKEMAN

The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Cant Stand Positive Thinking

Help! How to Become Slightly Happier and Get a Bit More Done

ALLEN LANE

an imprint of Penguin Canada,

a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited

Canada USA UK Ireland Australia New Zealand India South Africa China

Published in Allen Lane hardcover by Penguin Canada, 2021

Simultaneously published in the United States by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 120 Broadway, New York, 10271

Copyright 2021 by Oliver Burkeman

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Title: Four thousand weeks : time management for mortals / Oliver Burkeman. Names: Burkeman, Oliver, author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200318063 | Canadiana (ebook) 20200318152 | ISBN 9780735232464 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780735232471 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Time management.

Classification: LCC HD69.T54 B87 2021 | DDC 640/.43dc23

Ebook ISBN9780735232464

Book design by Gretchen Achilles, adapted for ebook

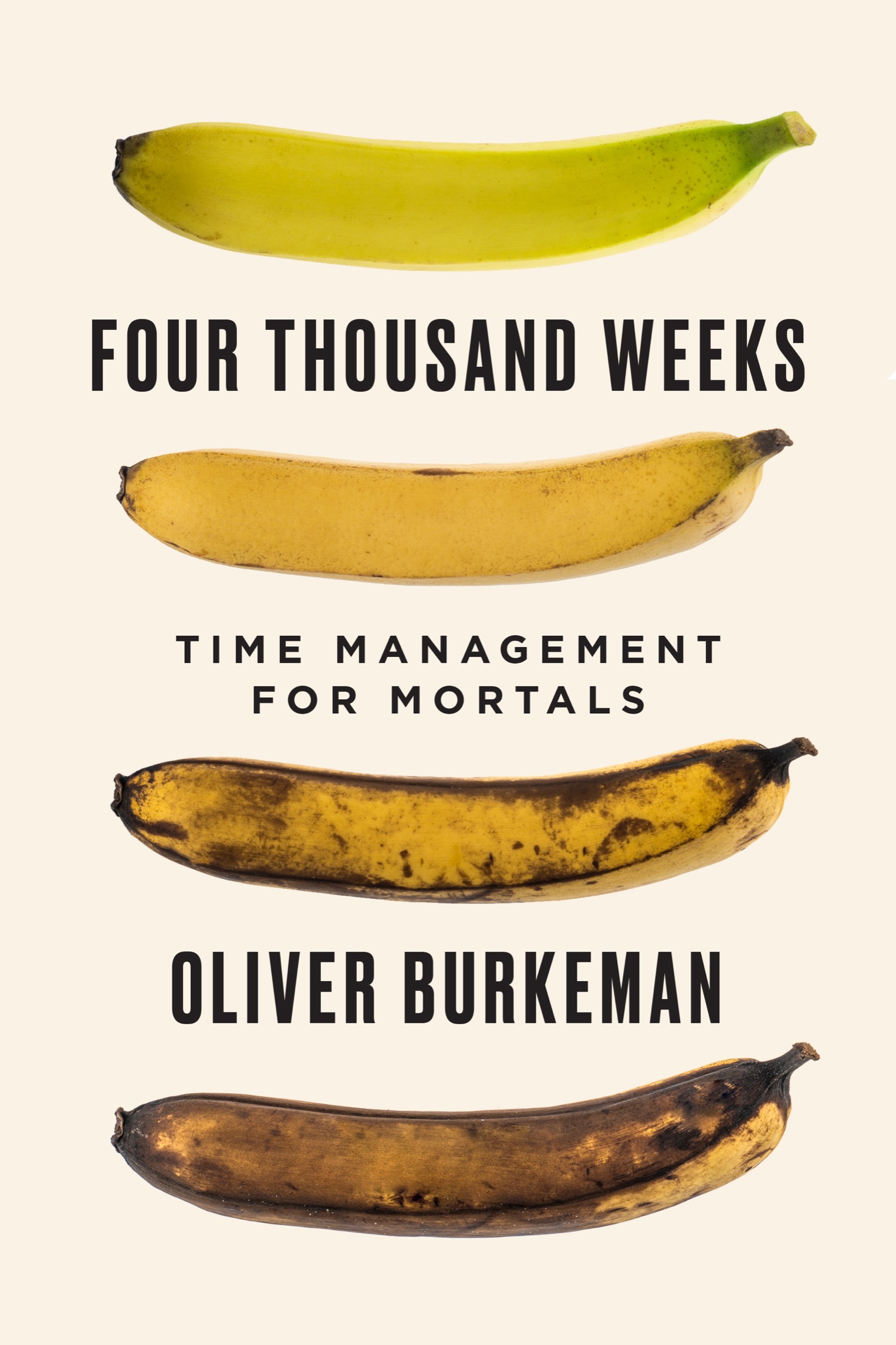

Cover design by Matthew Flute

Cover image Xinzheng / Getty Images

a_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

To Heather and Rowan

Its the very last thing, isnt it, we feel grateful for: having happened. You know, you neednt have happened. You neednt have happened. But you did happen.

DOUGLAS HARDING

What makes it unbearable is your mistaken belief that it can be cured.

CHARLOTTE JOKO BECK

Contents

Introduction: In the Long Run, Were All Dead

The average human lifespan is absurdly, terrifyingly, insultingly short. Heres one way of putting things in perspective: the first modern humans appeared on the plains of Africa at least 200,000 years ago, and scientists estimate that life, in some form, will persist for another 1.5 billion years or more, until the intensifying heat of the sun condemns the last organism to death. But you? Assuming you live to be eighty, youll have had about four thousand weeks.

Certainly, you might get lucky: make it to ninety, and youll have had almost 4,700 weeks. You might get really lucky, like Jeanne Calment, the Frenchwoman who was thought to be 122 when she died in 1997, making her the oldest person on record. Calment claimed she could recall meeting Vincent van Goghshe mainly remembered his reeking of alcoholand she was still around for the birth of the first successfully cloned mammal, Dolly the sheep, in 1996. Biologists predict that lifespans within striking distance of Calments could soon become commonplace. Yet even she got only about 6,400 weeks.

Expressing the matter in such startling terms makes it easy to see why philosophers from ancient Greece to the present day have taken the brevity of life to be the defining problem of human existence: weve been granted the mental capacities to make almost infinitely ambitious plans, yet practically no time at all to put them into action. This space that has been granted to us rushes by so speedily and so swiftly that all save a very few find life at an end just when they are getting ready to live, lamented Seneca, the Roman philosopher, in a letter known today under the title On the Shortness of Life. When I first made the four-thousand-weeks calculation, I felt queasy; but once Id recovered, I started pestering my friends, asking them to guessoff the top of their heads, without doing any mental arithmetichow many weeks they thought the average person could expect to live. One named a number in the six figures. Yet, as I felt obliged to inform her, a fairly modest six-figure number of weeks310,000is the approximate duration of all human civilization since the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia. On almost any meaningful timescale, as the contemporary philosopher Thomas Nagel has written, we will all be dead any minute.

It follows from this that time management, broadly defined, should be everyones chief concern. Arguably, time management is all life is. Yet the modern discipline known as time managementlike its hipper cousin, productivityis a depressingly narrow-minded affair, focused on how to crank through as many work tasks as possible, or on devising the perfect morning routine, or on cooking all your dinners for the week in one big batch on Sundays. These things matter to some extent, no doubt. But theyre hardly all that matters. The world is bursting with wonder, and yet its the rare productivity guru who seems to have considered the possibility that the ultimate point of all our frenetic doing might be to experience more of that wonder. The world also seems to be heading to hell in a handcartour civic life has gone insane, a pandemic has paralyzed society, and the planet is getting hotter and hotterbut good luck finding a time management system that makes any room for engaging productively with your fellow citizens, with current events, or with the fate of the environment. At the very least, you might have assumed thered be a handful of productivity books that take seriously the stark facts about the shortness of life, instead of pretending that we can just ignore the subject. But youd be wrong.

So this book is an attempt to help redress the balanceto see if we cant discover, or recover, some ways of thinking about time that do justice to our real situation: to the outrageous brevity and shimmering possibilities of our four thousand weeks.

Life on the Conveyor Belt

In one sense, of course, nobody these days needs telling that there isnt enough time. Were obsessed with our overfilled inboxes and lengthening to-do lists, haunted by the guilty feeling that we ought to be getting more done, or different things done, or both. (How can you be sure that people feel so busy? Its like the line about how to know whether someones a vegan: dont worry, theyll tell you.) Surveys reliably show that we feel more pressed for time than ever before; yet in 2013, research by a team of Dutch academics raised the amusing possibility that such surveys may understate the scale of the busyness epidemicbecause many people feel too busy to participate in surveys. Recently, as the gig economy has grown, busyness has been rebranded as hustlerelentless work not as a burden to be endured but as an exhilarating lifestyle choice, worth boasting about on social media. In reality, though, its the same old problem, pushed to an extreme: the pressure to fit ever-increasing quantities of activity into a stubbornly nonincreasing quantity of daily time.

And yet busyness is really only the beginning. Many other complaints, when you stop to think about them, are essentially complaints about our limited time. Take the daily battle against online distraction, and the alarming sense that our attention spans have shriveled to such a degree that even those of us who were bookworms as children now struggle to make it through a paragraph without experiencing the urge to reach for our phones. What makes this so troubling, in the end, is that it represents a failure to make the best use of a small supply of time. (Youd feel less self-loathing about wasting a morning on Facebook if the supply of mornings were inexhaustible.) Or perhaps your problem isnt being too busy but insufficiently busy, languishing in a dull job, or not employed at all. Thats still a situation made far more distressing by the shortness of life, because youre