THE PRINCIPIA

The publication of this work has been made possible in part by a grant from theNational Endowment for the Humanities, an independent federal agency. Thepublisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this bookprovided by the General Endowment Fund of the Associates of the Universityof California Press.

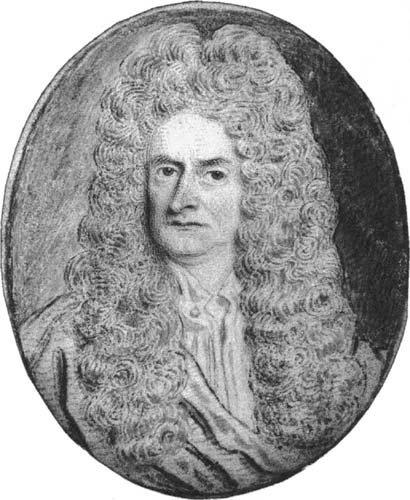

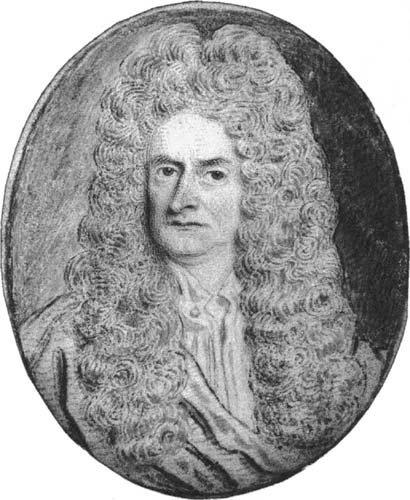

Portrait of Isaac Newton at about the age of sixty, a drawing presentedby Newton to David Gregory. For details see the following page.

Portrait of Isaac Newton at about the age of sixty, presented by Newton to David Gregory(16611708). This small oval drawing (roughly 3 in. from top to bottom and 3 in. fromleft to right) is closely related to the large oval portrait in oils made by Kneller in 1702, whichis considered to be the second authentic portrait made of Newton. The kinship between thisdrawing and the oil painting can be seen in the pose, the expression, and such unmistakabledetails as the slight cast in the left eye and the button on the shirt. Newton is shown in boththis drawing and the painting of 1702 in his academic robe and wearing a luxurious wig,whereas in the previous portrait by Kneller (now in the National Portrait Gallery in London),painted in 1689, two years after the publication of the Principia, Newton is similarly attiredbut is shown with his own shoulder-length hair.

This drawing was almost certainly made after the painting, since Knellers preliminarydrawings for his paintings are usually larger than this one and tend to concentrate on theface rather than on the details of the attire of the subject. The fact that this drawing showsevery detail of the finished oil painting is thus evidence that it was copied from the finishedportrait. Since Gregory died in 1708, the drawing can readily be dated to between 1702 and1708. In those days miniature portraits were commonly used in the way that we today woulduse portrait photographs. The small size of the drawing indicates that it was not a copy madein preparation for an engraved portrait but was rather made to be used by Newton as a gift.

The drawing captures Knellers powerful representation of Newton, showing him as aperson with a forceful personality, poised to conquer new worlds in his recently gained positionof power in London. This high level of artistic representation and the quality of the drawingindicate that the artist responsible for it was a person of real talent and skill.

The drawing is mounted in a frame, on the back of which there is a longhand notereading: This original drawing of Sir Isaac Newton, belonged formerly to Professor Gregoryof Oxford; by him it was bequeathed to his youngest son (Sir Isaacs godson) who was laterSecretary of Sion College; & by him left by Will to the Revd. Mr. Mence, who had theGoodness to give it to Dr. Douglas; March 8th 1870.

David Gregory first made contact with Newton in the early 1690s, and although theirrelations got off to a bad start, Newton did recommend Gregory for the Savilian Professorshipof Astronomy at Oxford, a post which he occupied until his death in 1708. As will be evident toreaders of the Guide, Gregory is one of our chief sources of information concerning Newtonsintellectual activities during the 1690s and the early years of the eighteenth century, the periodwhen Newton was engaged in revising and planning a reconstruction of his Principia. Gregoryrecorded many conversations with Newton in which Newton discussed his proposed revisionsof the Principia and other projects and revealed some of his most intimate and fundamentalthoughts about science, religion, and philosophy. So far as is known, the note on the back ofthe portrait is the only record that Newton stood godfather to Gregorys youngest son.

ISAAC NEWTON

THE PRINCIPIA

Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy

The Authoritative Translation

by I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman

assisted by Julia Budenz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses inthe United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in thehumanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by theUC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals andinstitutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Oakland, California

1999 by The Regents of the University of California

ISBN: 978-0-520-29073-0 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-0-520-29074-7 (paper)

ISBN: 978-0-520-96478-5 (ebook)

The Library of Congress has cataloged an earlier edition of this book as follows:

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Newton, Isaac, Sir, 16421727.

[Principia. English]

The Principia: mathematical principles of natural philosophy /Isaac Newton; a new translation by I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitmanassisted by Julia Budenz; preceded by a guide to Newtons Principiaby I. Bernard Cohen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-08816-0 (alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-520-08817-7 (alk. paper)

1. Newton, Isaac, Sir, 16421727. Principia. 2. MechanicsEarlyworks to 1800. 3. Celestial mechanicsEarly works to 1800.I. Cohen, I. Bernard, 1914 . II. Whitman, Anne Miller,19371984. III. Title.

QA803.N413 1999

531dc21

99-10278

CIP

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements ofANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 2002) (Permanence of Paper).

This translation isdedicated to

D. T. WHITESIDE

with respect and affection

Contents

Contents of the Principia

Publishers Note

This volume contains I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitmans 1999 translation ofNewtons Principia. In the preface and in the notes to the translation, Cohen refersto his Guide to Newtons Principia (the Guide). This volume contains anexcerpt from the Guide (A Brief History of the Principia). The Guide appears infull in The Principia: The Authoritative Translation and Guide, also available fromUniversity of California Press.

Preface to the 1999 Edition

ALTHOUGH NEWTONs PRINCIPIA has been translated into many languages, thelast complete translation into English (indeed, the only such complete translation)was produced by Andrew Motte and published in London more than two and ahalf centuries ago. This translation was printed again and again in the nineteenthcentury and in the 1930s was modernized and revised as a result of the effortsof Florian Cajori. This latter version, with its partial modernization and partialrevision, has become the standard English text of the