Routledge Revivals

Aristotle on Fallacies or the Sophistici Elenchi

Aristotle on Fallacies or the Sophistici Elenchi

With a

Translation and Notes by

Edward Poste

First published in 1866 by Macmillan and Co.

This edition first published in 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1866 by Taylor and Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under ISBN:

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-19051-4 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-429-20010-6 (ebk)

ARISTOTLE ON FALLACIES OR THE SOPHISTICI ELENCHI

WITH A

TRANSLATION AND NOTES

BY

EDWARD POSTE, M. A.

FELLOW OF ORIEL COLLEGE, OXFORD

OXFORD:

BT T. COMBE, M.A., B. PICKARD HALL, AND H. LATHAM, M.A. PRINTERS TO THE UNIVERSITY.

PREFACE.

ARISTOTLES explanation of the nature of Fallacies, if not satisfactory, seems to be as complete and intelligible as any that has since been offered. As his doctrines, indeed, are the source and substance of those of his successors, it appeared to the translator that the student of this theory would prefer to resort for instruction to the fountain-head, if it were made more easy of access.

Is not, however, the whole subject of Fallacies somewhat trumpery, and one that may be suffered, without much regret, to sink into oblivion ?

Possibly : but besides the doctrine of Fallacies, Aristotle offers either in this treatise, or in other passages quoted in the commentary, various glances over the world of science and opinion, various suggestions on problems which are still agitated, and a vivid picture of the ancient system of dialectic, which it is hoped may be found both interesting and instructive.

The text adopted is that of Bekker, except where emendation was absolutely necessary to the sense. Attention is called in the Notes to all changes except mere changes of punctuation.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

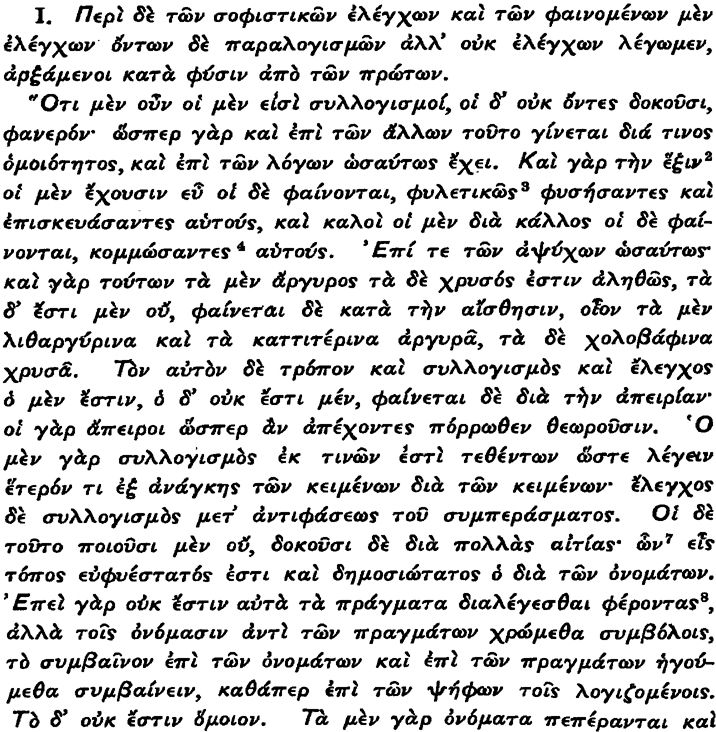

; and we thus begin, following the natural order of inquiry.

The existence, over and above real proofs, of seeming but unreal proofs is evident. As in other departments resemblance generates semblance, so in reasoning. Bodily vigour is sometimes genuine, sometimes, as in the tribal choruses, simulated by the aid of dress : beauty is sometimes natural, sometimes counterfeited by cosmetics. So in lifeless objects : some bodies are genuine silver or gold, others are not silver or gold but seem such to the sense; as litharge. Confutation is a proof whose conclusion is the contradictory of a given thesis. Some proofs and confutations have not really these characters, but seem to have them from various causes; and one multitudinous and widespread division are those that owe their semblance to names. For, not being able to point to the things themselves that we reason about, we use names instead of the realities as their symbols, and then the consequences in the names appear to be consequences in the realities, as the consequences in the counters appear to the calculator to be consequences in the objects represented by the counters. But it is not so. For names, whether simple or complex, are finite, realities infinite; so that a multiplicity of things is signified by the same simple or complex name. As, then, in calculation, those who are unskilled in manipulating the counters are deceived by those who are skilled, so in reasoning, those who are unacquainted with the power of names are deceived by paralogisms both when they are parties to the controversy and when they form the audience. From this cause, and others to be enumerated, there exist proofs and confutations that are apparent but unreal.

Now it answers the purpose of some persons rather to seem to be philosophers and not to be than to be and not to seem; for Sophistry is seeming but unreal philosophy, and the Sophist a person who makes money by the semblance of philosophy without the reality; and for his success it is requisite to seem to perform the function of the philosopher without performing it rather than to perform it without seeming to do so. Now, if we define by a single characteristic, the function of a man who knows is to declare the truth and expose error respecting what he. knows. The former of these powers is ability to stand examination in a subject, the latter is ability to examine another who professes to know it. Those, then, who wish to practise as Sophists will aim at the kind of reasonings we have described, for it suits their purpose, as the faculty of thus reasoning produces a semblance of philosophy, which is the end they propose.

The existence, then, of such a mode of reasoning, and the fact that such a faculty is the aim of the persons we call Sophists.

.

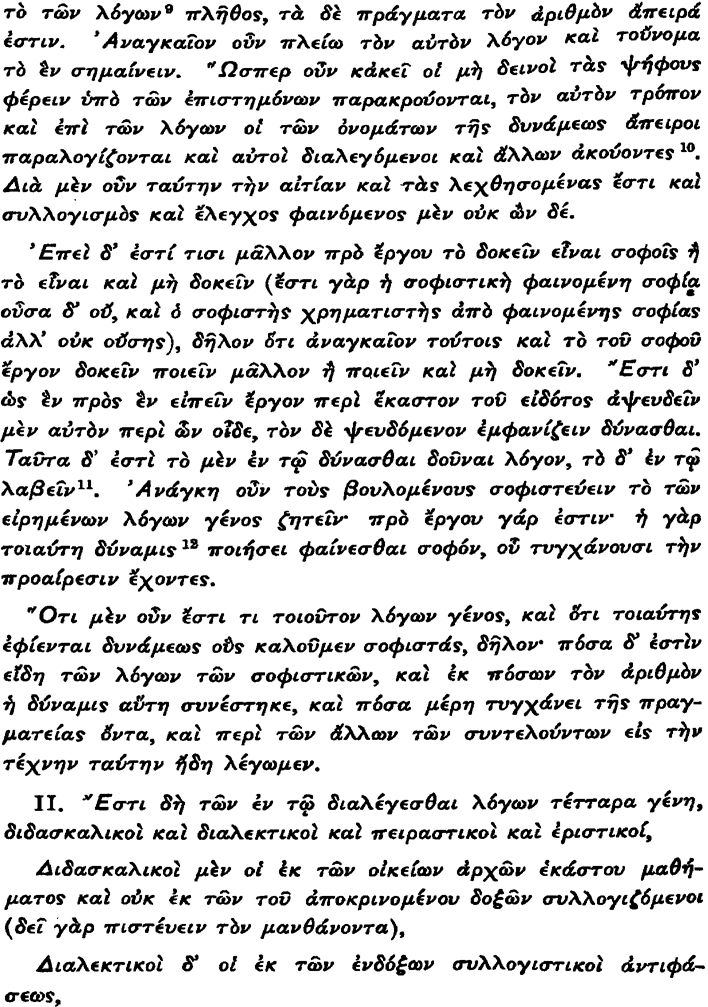

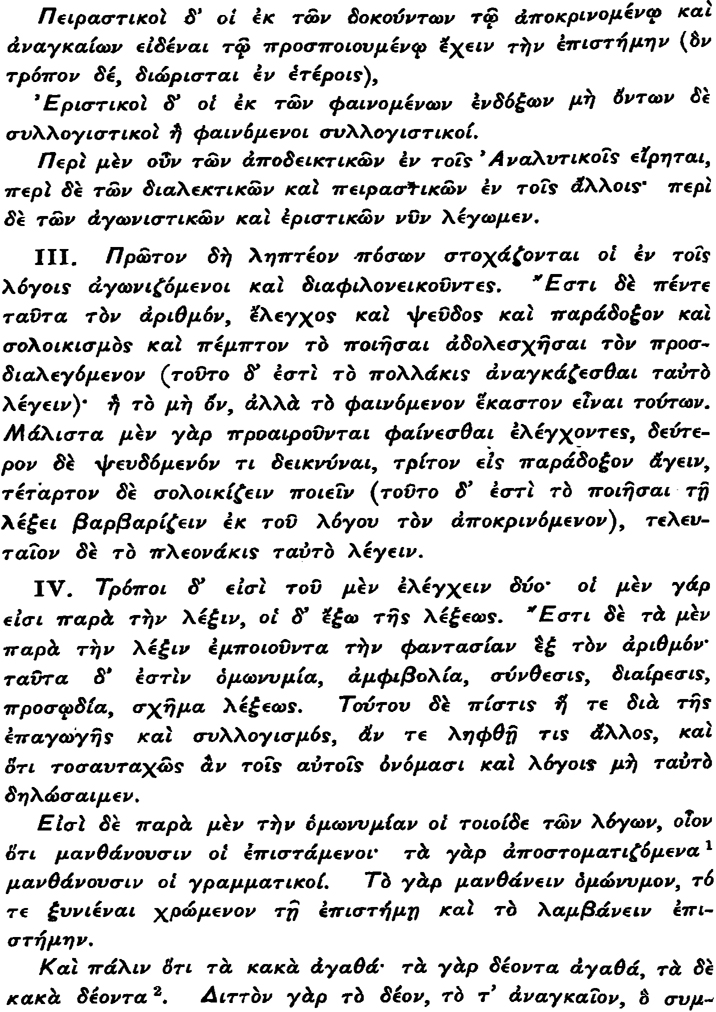

Didactic reasonings conclude from the scientific principles appropriate to a subject, and not from the answerers opinions, for the learner is required to believe :

Dialectic employ as premisses probable propositions and conclude in contradiction to a thesis :

Pirastic employ as premisses the opinions of the answerer on points that ought to be known by the pretender to science, with the limitations elsewhere mentioned :

Eristic conclude from premisses which seem but are not probable, or only seem to conclude from probable premisses.

Demonstrative reasonings having been discussed in the Analytica, Dialectic and Pirastic elsewhere, contentious and Eristic reasonings remain to be investigated.