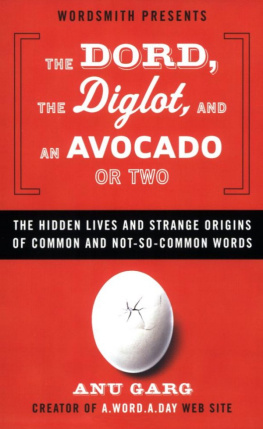

Rosalie Baker - In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins

Here you can read online Rosalie Baker - In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: ePals Publishing, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins

- Author:

- Publisher:ePals Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Words are slippery things. Words are also difficult to define. They fascinate me both for themselves and for the history they sometimes reveal. We all know what a cat is, but try to define the word cat without either pointing to a cat or using the word feline in the definition. Dr. Samuel Johnson in his great dictionary of the English language defined cat as: a domestic animal that catches mice. Although his definition is true of most cats, it is not true of all; and there probably are other domestic animals that can be taught to catch mice.

Words are curious, often with curious histories, as you will learn from this book. Check out candidate or senate, for instance. My wife remarked the other day that the day was close. This sense of the wordhot and stiflingwas popular in 1533 (and is in current use, but not commonly used). A person may be described as being close with a dollar, which means that he is cheap, a skinflint, or stingy. We can see how this second meaning fits with our current belief about the meaning of close; but connecting the word to the weather or the atmosphere in a room seems a stretch. Words can be used to convey what we might think of as many different meanings.

Words are also extremely important. If we do not know the word for a thing, we cannot easily talk about that thing without using the word thing or pointing or describing what the object is used for. Were forced to resort either to gesture or circumlocution (a lengthy way of expressing something). We cannot be ignorant of words connected with international relations or computers or the national economy or the life of the mind. If we are, we will find ourselves unable to take part in discussions of matters important to ourselves and to society.

I recently saw the word donator in a local paper. We all know what the word must mean, and we know that it refers to the person who donates. But does it exist in the English language? One of my dictionaries cites it, another does not. Which are we to believe? English possesses a perfectly good word (donor) that would seem to serve the purpose intended; or is there some distinction to be made between a (possibly one-time) donator and a (regular and systematic) donor? I do not know, and will have to wait and see.

In addition to being important, the study of words is exciting, as you will discover by reading this book. From it you will learn about many words and their history, a history that is sometimes interesting and unexpected, as with the phrase meet the deadline. Through these words and others you will marvel at human creativity, improve your vocabulary, and have a lot of fun.

Dr. William F. Wyatt

Professor of Classics, Emeritus

Brown University

Ever since my first week in 9th-grade Latin class, I have enjoyed dissecting words. I enjoyed learning just what words really mean and how these meanings had evolved. I already spoke English and Portuguese, so Latin seemed to fill a gap of understanding. It allowed me to see the relationships between words and the people who speak them today, and the people who used them in the past. My love of languages continued through high school and into college and graduate school. As I studied French, German, and Greek, each again broadened my perception of language and how words reflect a peoples beliefs and customs.

In 1981, when my husband, Charles Baker, and I started the monthly magazine now called CALLIOPE , we decided to include in each issue a column on words and their origins. That column, Fun With Words, still appears in each issue of CALLIOPE today. Fun With Words became a mini-education for me as I researched words in languages that I did not speak or read. I had long known that fossil traced its roots to the Latin noun fossa, which translates ditch and symbolized something that had been dug up from the ground. But I had no idea that bandanna and bungalow each traced its roots to Hindi, a language spoken in India, or that typhoon was an adaptation of the Chinese phrase taifeng, meaning great wind. Another surprise was discovering that the cloth named mohair was an adaptation of the Arabic word mukhayyar, meaning fine cloth.

It is a treat for me to research new words for each issue of CALLIOPE , but, as the years passed, I wanted to find a way to gather together all Id learned and pass it on to new readers. We decided to create this book, which features not only a lively discussion of word origins, but also new information that is related in some way to the word derivations on a particular page. We call these tidbits PS, as in postscript (you can see its origin ).

Lou Waryncia, the editorial director at Cobblestone Publishing; Marc Aronson, the publisher of Cricket Books; Ann Dillon, the art designer at Cobblestone Publishing; and Carol Saller, editor at Cricket Books, encouraged me. I wish to thank all four for their support and input.

Just as the Fun With Words column cannot include all words related to the theme of a CALLIOPE issue, so this book cannot include the origins of all English words and phrases. I have included my favorites and encourage all of you to use them as a starting point for investigating the fascinating history contained within every word we read and write. You will soon find that an awareness of what word or phrase is appropriate and effective in a particular situation gives you a distinct advantage in school, on the job, and with your friends.

This book is a result of my lifetime of journeying through the words we use into the lives and history of people all around the world. I hope it is also the beginning of your quest to look inside words to the stories they tell.

Rosalie Baker

Ever wonder how the word orchestra evolved to mean both the location of the best seats in a theater and a large group of musicians who play together? You may consider yourself a maestro of arts and literature information after you have read this chapter.

A cappella

This musical term, meaning without accompaniment, comes from the Frenchman Martin of Tours. Around the year 326, 10-year-old Martin rejected the gods of ancient Rome to follow the beliefs of the growing Christian church. Martin later became a missionary in Gaul and, in 360, founded the first monastery there. Regarded as a holy man and a miracle worker, Martin was honored as a saint after his death. The chief officials of Gaul placed his cloak, considered a holy relic, in a small room in his church. The room became known as the capella, which is Latin for little cloak. The guardian of the cloak became the capellanus. Religious services were held in the capella. While there was singing, no musical instruments were used in the capella. For this type of music, the Italians coined the phrase a capella, meaning in chapel style. Other languages quickly borrowed the phrase to mean singing without musical accompaniment. The French later adapted capella and capellanus to chapelle and chapelain. In English, the words became chapel and chaplain .

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins»

Look at similar books to In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book In a Word: 750 Words and their Fascinating Stories and Origins and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.