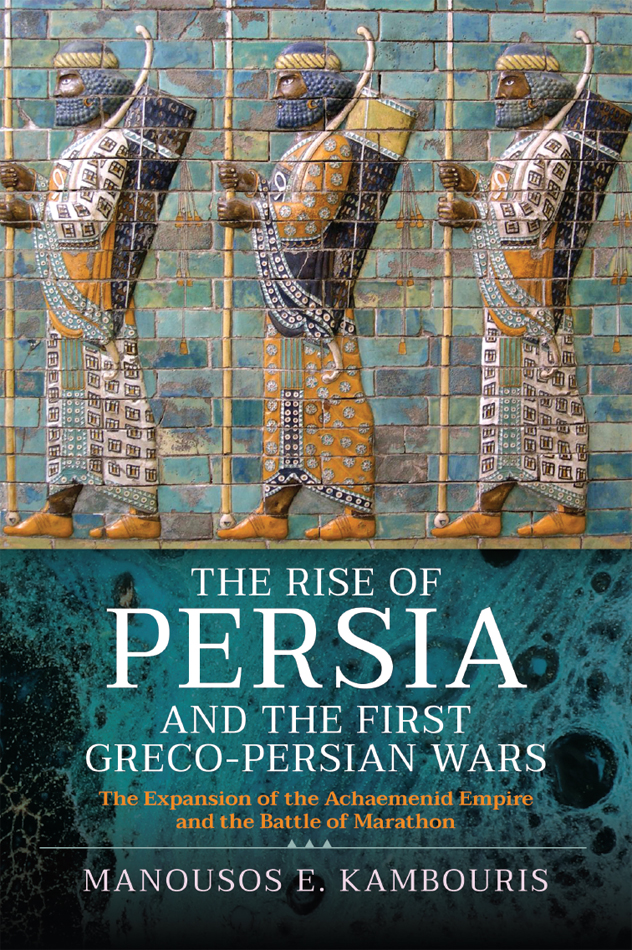

The Rise of Persia and the

First Greco-Persian Wars

The Rise of Persia and the First Greco-Persian Wars

The Expansion of the Achaemenid Empire and the Battle of Marathon

Manousos E Kambouris

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Manousos E Kambouris 2022

ISBN 978 1 39909 329 3

eISBN 978 1 39909 330 9

Mobi ISBN 978 1 39909 330 9

The right of Manousos E Kambouris to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

This book is dedicated:

to my friend, Professor George P. Patrinos, without whose support it would not have materialized;

to my uncle Glystras without whose encouragement and help I might have never embarked on any authorship project;

and to the loving memories of my Mom Dimi, who taught me to speak and write; and of my grannie Pitsa who insisted on studying diligently and doing ones homework although her teaching at the tender age of 4 showed that school has nothing to do with learning and education; its all about tutoring.

Introduction:

A True Cultural World War

R evisiting the causes, the infringing and defining past and the conduct of the clash between the Greeks and the Persians in the sixth and fifth century BC a true world war with participating troops from three continents 2,500 years ago may be a Herculean task. This is so, especially if attempted with a focus on executive options and decisions at political, strategic, operational and tactical levels. The surprise at Marathon, the guile in Salamis, the valour in Thermopylae and the cold efficiency, drill and skill in Plataea created the picture of the known history of the world as it is, but the details of how and why the events unfolded as they did are hazy and dubious in their interpretation. It was a complicated time in politics, ideology and war-making. Intrinsic facts and motives, hidden, known, understood and misunderstood are intermingled to this day and mar the historical perception of the first clearly ideological struggle between a new world order promising Light, Justice and Order yet delivering oppression and exploitation and the ones that simply wanted nothing to do with such heavenly bliss

It was a prolonged struggle, and the two antagonists thought of it as one, or more, episodes of an older East-West struggle, although this may be a poor choice of words. It was the continuation of previous events, and if they did not believe so, they did pretend it to be so. The concurrent phase of this struggle opened up after the Trojan War, when the Kingdom of Lydia became a world power and subjugated the young colonies of the Greek Nation(s) in Western Asia Minor. The dynasty and the dynast changed, but since then a continuous pressure was to come from the East, up to this day; sometimes repulsed, sometimes exceeding the breaking point and surging across the Aegean. The Greco-Persian Wars of 540479 were just a phase in this struggle the Greeks had since perhaps the times of the Hittites, well in the 2nd Millenium BC . But this phase was massive and involved new technology, new methods, clearly of a diverging evolutionary course in technology, processes and very different ideologies, making it a dissimilar opponents game, highly asymmetric in every conceivable way. Previous episodes were symmetric clashes between similar opponents.

No matter the approach followed in trying to elucidate the events, the motives and the ulterior thoughts, the researcher will eventually face a cardinal event: the build-up of the two factions in Greek politics: the Medizing one, siding with the Persian Empire (the Medes for the Ancient Greeks rather than the Persai as is historically correct), and the national-minded one, attempting resistance against the odds. The core issue is to correctly associate and deconvolute the known facts, as there are many missing links and dark spots, and also to interpret them correctly, as there are many vague issues due to a variety of reasons. The past of the two antagonists and other involved parties is helpful, as they both claimed heritage from powers of old. And a comparison with practices and procedures proven during other, better recorded historical times may well dissolve some prejudice and indoctrination of scholar research of times past and present to a better understanding of an era that defined world history as none other.

Part I

Chapter 1

The (Hi)story of the Historian

O ur understanding of the Persian wars relies heavily on Herodotus, whose account is full, extensive, relatively complete and chronologically near the main events; a mere two generations from the initial events at most, one generation from the most important ones. There are indeed gaps in the narrative, lacunas and, most importantly, misunderstandings, but Herodotus had access to first-class material, as he saw, transcribed and translated, or had someone translate for him, epigraphic material. He also interviewed persons of authority, possibly protagonists of the events and/or their direct descendants and this material was expanded by personal experience. He had himself visited theatres of the action, and spoke Persian and perhaps some other language(s) of the Levant. He was both a traveller and a national of a city focal to Aegean trade, previously under the Persian yoke. He might have been a merchant himself or the spawn of such a family.

All other historical accounts, such as Diodorus and Plutarchs, are later by some centuries and secondary, based on now-lost original works. More to the point, Diodorus is extremely brief; he obviously made a synopsis of his source(s), and Plutarchs shows no cohesion, continuity or completeness. He narrates the events through the biographies of some of the protagonists, and thus outside any operational or even historical context. Some important pieces can be salvaged from other sources, such as: the work of Ktesias, chief physician of the Persian Court some 80 years after the end of the Great Greco-Persian War; rhetoric collections; Art (representative and vocal, the latter exemplified by the tragedy Persai of Aeschylus) and, most importantly, from the travel syllabus of Pausanias and the Stratagems of Polyaenus. All these together have no meaning without the full story of Herodotus and the same is true for some Persian sources.