Text 2019 University of Alaska Press

Published by

University of Alaska Press

P.O. Box 756240

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6240

Interior design by Kristina Kachele Design, llc

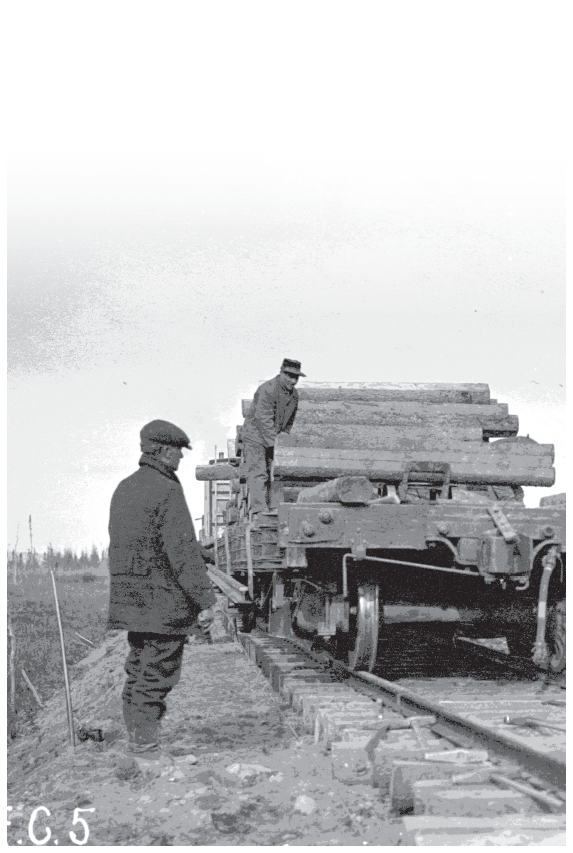

Cover image: Laying steel rails for construction of the Alaska Railroad. Once the route was determined, crews began working north from Seward and south from Fairbanks. The route was divided into three sections with a commissioner in charge of each section (UAF Rasmuson Library Archives UAF-1984-75-8).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Alton, Thomas L., author.

Title: Alaska in the Progressive Age / by Tom Alton.

Description: Fairbanks, AK : University of Alaska Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018061189 (print) | LCCN 2019001124 (ebook) | ISBN 9781602233850 (e-book) | ISBN 9781602233843 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: AlaskaHistory18671959. | Progressivism (United States politics)

Classification: LCC F909 (ebook) |LCC F909 .A47 2019 (print) | DDC 979.8/03dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018061189

FOREWORD

ON SEPTEMBER 3, 1938, Ernest Gruening paid a visit to James Wickersham at his home on a quiet street in the hills above Juneau. Gruening was then an official with the Interior Department, where he oversaw the administration of federal territories, including Alaska. A year later, he would be appointed governor of the territory. Wickersham, eighty-one years old and retired after a career as lawyer, federal judge, and Alaskas congressional delegate, spent his days dabbling in legal work and dictating letters to his wife, Grace, whose help he required since he was going blind. For an hour or so, the two men discussed current issues in Alaska. As was his habit, Wickersham grumbled about uninformed congressmen, government obstructionists, outside corporate interests, and everyone else he believed was holding Alaska back. A few weeks later, the former delegate fired off a thirty-page letter to the future governor, castigating what he called the felonious mining, logging, railway, and steamship trusts that epitomized monopoly and greed. I will write what I know to [Gruening], Wickersham wrote in his diary that fall, and let him work out the facts. Many years later, when Gruening was himself eighty-six years old, he remembered the tte--tte with Wickersham, writing in his memoir how the delegate spoke with vigor about his many fights against the looting of Alaska by J. P. Morgan, the Guggenheims, and other corporatists.

That James Wickersham remained a pugnacious advocate for Alaska even in his last days as a nearly blind octogenarian should surprise no one. As Tom Alton explains in this insightful and thoroughly researched book, the always-uncompromising Wickersham really came into his own as Alaskas congressional delegate, serving seven nonconsecutive terms between 1908 and 1933, during which he delivered countless stem-winders on the House floor and relished every fight, in part for what he could deliver to Alaska when he won but also for the mere sport of it all.

Alton notes that for all the political skills Wickersham possessed, he also had the good fortune to arrive in Washington at the height of the Progressive Era, a time when the federal government responded to the social and economic effects of industrialization by assuming a more active role in regulating big business, managing the nations natural resources, and funding infrastructure projects for public benefit. It was Alaskas good fortune too. Wickersham leveraged those prevailing political winds to the long-term benefit of the territory and its residents. Major gold strikes in the Klondike, Nome, and Fairbanks had convinced Washington to begin paying attention to the nations northernmost territory, and Wickersham was instrumental in establishing an elected legislature as well as Alaskas first college, its largest railroad, and Mt. McKinley National Park.

This book makes a remarkable contribution to Alaska history by bringing all those stories together under the umbrella of Progressivism, a widely studied movement in American history but one whose impact on Alaska has remained relatively unexplored. As Alton points out, the political, economic, and social development of Alaska in the early twentieth century was going to happen one way or another. The discovery of gold, stampede of settlers, and steamships full of tourists clamoring to see glaciers and totem poles would see to that. But if some degree of transformation was a given, there was still nothing inevitable about the nations response, nothing preordained when it came to railroads, national parks, territorial legislatures, or any other mechanism by which the federal government might see to Alaskas future. To be sure, the legislative dynamo that was James Wickersham played a major role in steering that course, but the developments also occurred within a unique set of circumstances as Americans responded to the rapid modernization happening in their country. Historians are always mindful of the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy, the misguided notion that because one event follows another, it must therefore have been caused by it. Alton is at his best when he distinguishes, with meticulous detail and carefully chosen words, that Progressivism did not cause Alaskas early territorial development but rather exerted a profound influence on what was already happening in the proverbial last frontier. National currents worked to establish the political foundationas well as the literal foundation in the case of infrastructure projects such as the railroadon which todays Alaska stands.

The author similarly brings a penetrating yet nuanced scrutiny to Wickershams long-standing claim that the federal government consistently neglected to promote Alaskas development, a lament Gruening would advance throughout his own political career. The attention of Washington and the many gains of the Progressive Era complicate the narrative. It is to Altons credit that he avoids trying to prove or disprove the theory of neglect, choosing instead to focus on how the politically potent idea functioned in public discourse at the time. When Gruening visited Wickersham on that late-summer day in 1938, he asked the former delegate whether he viewed his prized railroad bill as a victory against corporate control of Alaska. Although it operated at the margins of economic profitability, the federally owned railway still epitomized the progressive ideal of public resources managed for public benefit. Wickersham valued the railroad, he told Gruening, but wished he could have done more. I hoped that the government would build not merely one but two railroads over different routes, he stated. The legislation I sponsored and Congress approved authorized two routes, but only one was built. Neglect indeed!

The Progressive Era in Alaska was as complex, contradictory, and meaningful as any in the states history. I hope readers enjoy Tom Altons book as much as I did.

Ross Coen, University of Alaska Fairbanks Department of History