For the best reading experience, the following application settings are recommended:

Foreword

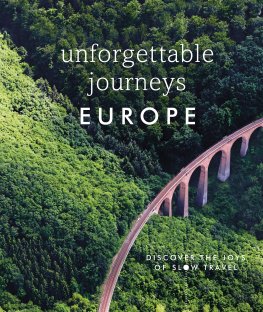

Those who sail close to the shore never discover new lands. A young American student, full of youthful enthusiasm, said this to me while I was teaching archeology at the American University of Rome. I thought how well the words, adapted from a 1925 novel by French writer Andr Gide, summed up the human desire to travel.

For some 60,000 years, humans have explored the world, out of necessity and curiosity. Our ancestors, who first lived in caves and makeshift shelters, hunted and foraged. The rivers were both a source of food and a means of transportation. As humans began to herd animals, they needed to travel for pasture. So began the fascinating story of humanitys journey, filled with light and shade.

The most significant inventions in antiquity were the sail, which transformed rafts into boats, and the wheel, which made it possible for our ancestors to travel wide distances. Humans also learned to harness animals to pull chariots and coaches. The Ancient Romans developed a highway system that linked their ever-expanding empire. The Ancient Greeks, meanwhile, devised a complex astrolabe to chart the seas using the stars and planets, and a system of longitude and latitude, enabling sailors to undertake lengthy voyages. Despite these astronomical advances, for centuries mariners believed the Earth was flat, but still sailed the oceans. They were aware of the dangers of their missions but resolutely continued to push the boundaries. Others scaled the snowy heights of unknown mountains, often for the thrill and sense of adventure. Many risked and lost their lives for little more than the spectacular view from the highest peaks in the world.

Each generation has contributed to novel means of travel. Leonardo da Vinci, for example, conceived the original idea of a helicopter in 1493, but it was only in the last century that airborne travel became commonplace. Today, luxury tourism is the largest-growing industry in the world. Voyages into space continue to broaden our understanding of the vast expanses beyond our galaxy, yet the sea floor beneath the oceans that cover 70 percent of our planet still remains largely unexplored.

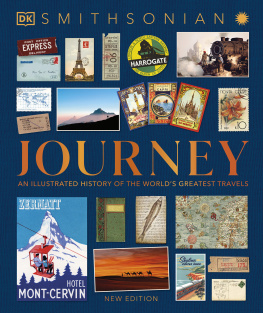

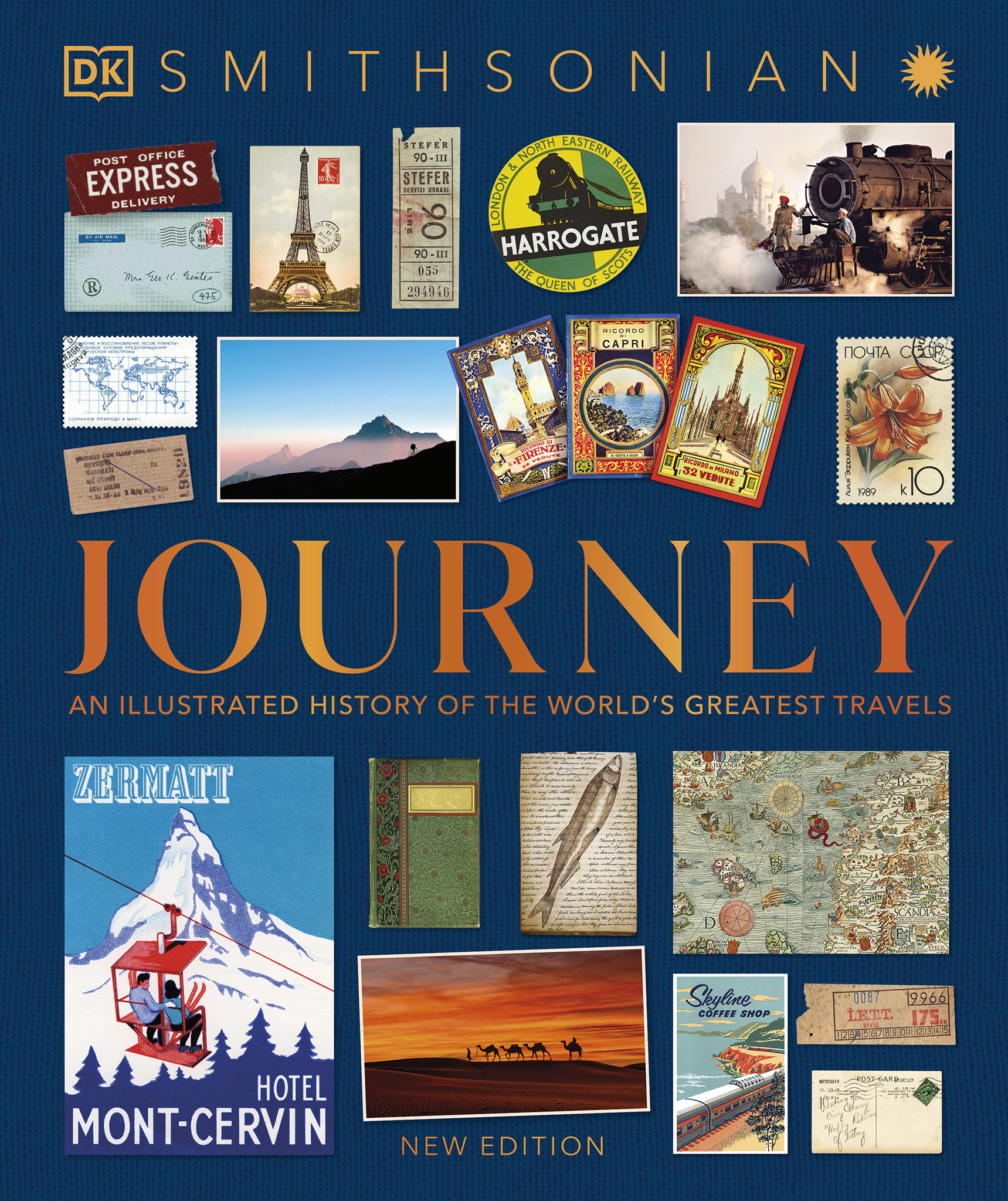

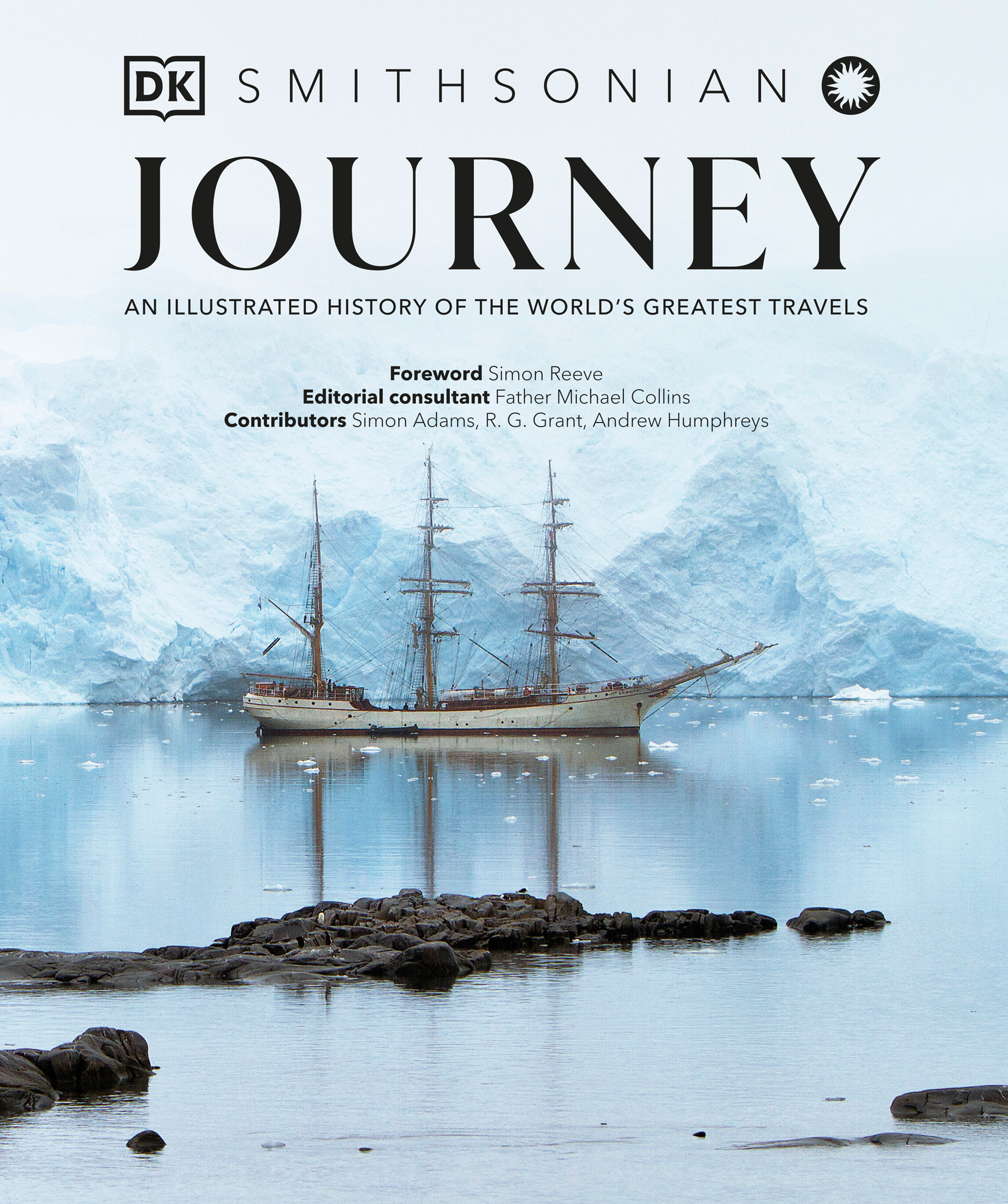

Journey explores travel in all its varied forms. In this wonderful book, we have gathered extraordinary accounts of exploration, exile, pilgrimage, refuge, crusades, trade, colonization, and conquest. I hope that as you read it and enjoy the stunning images, in your minds eye you will leave the shores and push out into the deep. Many people have gone before us, and we can be sure that many more will pass beyond the limits of our present horizons.

MICHAEL COLLINS

Introduction

Humans have always been wanderers. Our distant ancestors were nomads for thousands of years before they founded any settlements. Beyond the many practical motives for travelthe pursuit of trade, warfare, pilgrimage, the search for new lands to settle or conquerthere has always been a more primitive human urge, the impulse to find out what lies over the hill, trace a river to its source, sail an unfamiliar coastline, or explore ever further into the unknown.

Looking back from the present high-tech age, the scale of the journeys once made by people who traveled only on foot, on horseback, or in small boats propelled by sails or oars is simply astonishing. The soldiers of Alexander the Great marched all the way from Greece to northern India, while the Mediterranean sailors of the ancient world ventured as far as the southern tip of Africa. Without so much as a compass to guide them, the Vikings sailed from Scandinavia to the shores of North America, and Polynesian sailors set off across vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean in search of new islands to colonize.

Long journeys to distant places were not the preserve of a bold minority of adventurers. In medieval times, thousands of pilgrims from Christian Europe undertook arduous journeys by land and sea to visit the holy places of Jerusalem, as did Muslims to Mecca, and merchants transported goods in caravans across the arid wastes of the Sahara Desert or along the mountainous Silk Road from China to Europe.

About 500 years ago, the oceanic voyages of Christopher Columbus and other European sailors made it possible for cartographers to draw up broadly accurate maps of the world for the first time. But for centuries after these voyages, many areas of the world remained a mystery. Even in the 20th century, people were still foraying across uncharted deserts or jungles, or to places where no human had set foot before, such as the Arctic and Antarctica.

As steamships, railroads, and, later, aircraft made long-distance journeys more common, the romance of travel was sustained by luxury and novelty, from the Orient Express to flying boats. More recently, the oceans and outer space have become targets for exploration, and the lust for adventure has been sated by treks and journeys that challenge human endurance. More recently still, the COVID-19 pandemic has reminded us that travel is a privilege, not a right, while the climate crisis is presenting new challenges and opportunities for sustainable eco-travel and conservation-centric experiences.

I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travels sake. The great affair is to move.

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON, TRAVELS WITH A DONKEY IN THE CEVENNES

Descelierss world map

This map was created in around the 1530s by French chart maker Pierre Desceliers. Made in the style of a sea chart, it has compass roses and navigation lines, but was clearly a work of art rather than for use at sea.

THE ANCIENT WORLD

3000 BCE400 CE

THE ANCIENT WORLD | CONTENTS

Introduction

the ancient world, 3000 BCE400 CE

The ability to travel swiftly over long distances is common to many species, but bipedalism, coupled with a slightness of build, hunter-gatherer instincts, and an apparently insatiable curiosity, are all hallmarks of homo sapiens a creature for whom no stone, it seems, can be left unturned. Explorationthat restless need to shine light on the unknownis the lifeblood of the species. Thanks to our ability to conceptualize, we can imagine better worlds and search for themsometimes cooperating, sometimes warring along the way.