Copyright 1998 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201.

All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/.

All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material.

The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

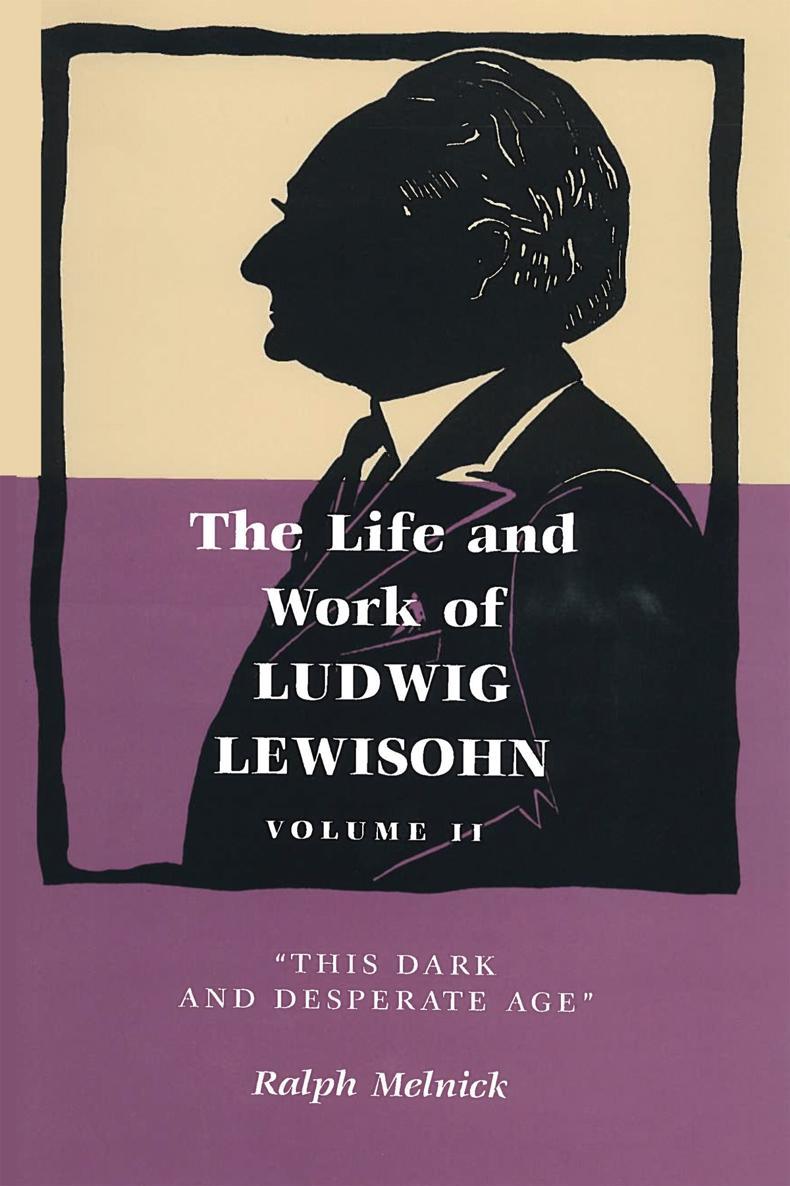

Melnick, Ralph.

The life and work of Ludwig Lewisohn / Ralph Melnick.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Contents: v. 1. A touch of wildnessv. 2. This dark and desperate age.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4504-7 (paperback); ISBN 978-0-8143-4503-0 (ebook)

1. Lewisohn, Ludwig, 18821955. 2. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. I. Title.

PS3523.E96Z76 1998

813'.52

[B]DC21 9736411

Wayne State University Press gratefully acknowledges The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives (AJA) for their contributions to this volume, including the use and publication of a selection of Ludwig Lewisohn photographs. To access these photographs and many other collections preserved at the AJA, please visit the AJA website at www.AmericanJewishArchives.org.

The Press also wishes to thank the following individuals and institutions for their generous permission to reprint material in this book: Brandeis University; Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Guy Chabot; College of Charleston; Harper Collins Publishers; Harry Random Center at The University of Texas at Austin; and Presses Universitaires de France.

Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux:

Jacket design from The Case of Mr. Crump by Ludwig Lewisohn. Copyright 1947 by Ludwig Lewisohn.

Jacket design from Goethe: The Story of a Man by Ludwig Lewisohn. Copyright 1949 by Ludwig Lewisohn.

Jacket design from In a Summer Season by Ludwig Lewisohn. Jacket Design by Lili Cassel. Copyright 1955 by Ludwig Lewisohn.

Exhaustive efforts were made to obtain permission for use of material in this text. Any missed permissions resulted from a lack of information about the material, copyright holder, or both. If you are a copyright holder of such material, please contact WSUP at .

http://wsupress.wayne.edu/

P REFACE

I N 1965, THREE B RANDEIS University students came to St. Matthews, South Carolina, to help with voter registration among the towns largely disenfranchised black community. With the exception of the court clerk, none of the players in this dramaneither students nor townspeopleknew anything of the man from St. Matthews who had in so many ways struggled to remake the country in which this was now possible. He had been largely forgotten in the decade since his death, but it was here, in this up-country village, that Ludwig Lewisohn, social iconoclast and founding member of the Brandeis faculty, had seventy-five years earlier spent his first days as an immigrant child in America. It was here that he had first tested this new world, and found it wanting.

Though from time to time his name has appeared in one place or another, in America and abroad, Ludwigs vast contribution to literature, the theater, social change, and the struggle for Jewish survival and renewal has remained all but forgottenas he believed it would. He had harbored few illusions. Once of great concern, this loss of fame seemed not to matter after a time. Where once the immortality urge had driven him to write, he had in the course of his years found a more important reason to continue. Had he not, he might have laid aside his pen when the veil of obscurity began to descend upon his prominence and notoriety. But he simply could not remain silent before the injustice and moral error that had moved him to such great efforts, even as his energies waned in the final days of his life. Man is only half himself, he affirmed, the other half is his expression. If he had experienced more than his share of pain, disappointment, and abandonment, there was in him an underpinning of prophetic belief that would not allow him to desert the fight. Yet if he could offer so positive an example, how had he come to this end? Why the obscurity when lesser men remained known, even celebrated?

I was only nine years old when Lewisohn died in 1955, and a dozen more years would pass before I first encountered Up Stream , his piercing critique of America, written more than four decades earlier. I had found it during a time of national turmoil and personal soul-searching, and despite its distance in time, it rang true in so many waysas it still does. Fifteen years later, I would begin to seek a better understanding of his experience and to write about it. The search for an answer would demand these many years, and in its pursuit, I would learn to take seriously his advice, that all who would explore the recorded deeds and sayings of a famous man [must] search among them for hints of secret things from which to weave a clear and animated picture of his life. In the years since I began, there have been reasons enough to stop. Each life has its own detours. But few biographers choose subjects who have not in some way already touched their lives. There is a resonance. Something compels, if only the questions that echo in ourselves.

How might understanding his fall into obscurity help us, I wondered? At the height of his fame, Ludwig had argued that all sound creative art is rooted in a ghetto, a notion I discovered to be both true and damaging to him in an America not yet willing to accept the realities of ethnicity. I am still necessarily functioning as the product of that smaller ghetto which, in fact, I had never left, which no one can leave but only pretend to leave. As an exile in search of himself and his community, as the outsider shorn of the need to defend the world as it is, might he not have something to teach us for our own time of radical change? My hierarchy of values is different, he proclaimed openly as a part of his insistence upon the right to share in the larger society, but on his own terms.

Such forthrightness, however, had contributed not only to his vision of the life around him and to his rejection by those against whom he had rebelled, but to attacks by those whose struggle for a more just society he had once shared. They, too, could brook no dissent. Pacifist and socialist, he had come ultimately to question even these positions as the years brought the challenges of Nazism and Stalinism. If others wished to hold him to ideas they had once espoused together, he could respond only as the person who had emerged from the struggles of his day with a deepening Jewish consciousness. And if Zionism remained for some either too bourgeois or an article of old-world faith, he could not so readily dismiss the liberation of his fellow Jews. The world had grown too dangerous for that, too uncaring and worse, and he, too deeply committed to his Jewish self. How could he set aside the obvious in order to defend the abstract? Above all else he was a Jew, and his values and sensibilities had been stamped irrevocably by that fact. Who else would he be if he would not be himself, that person he had become by force of will?