Table of Contents

Landmarks

Click on the links below for highlights |

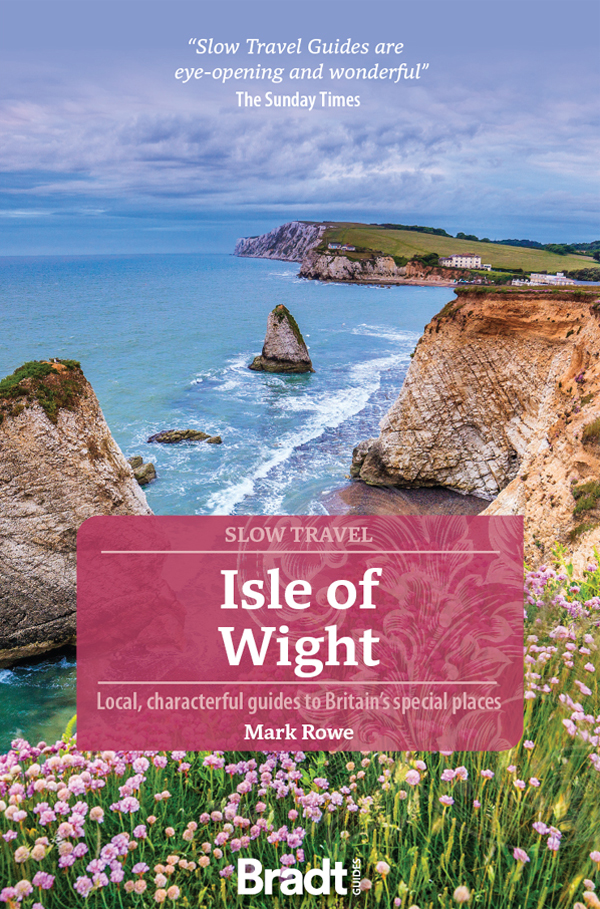

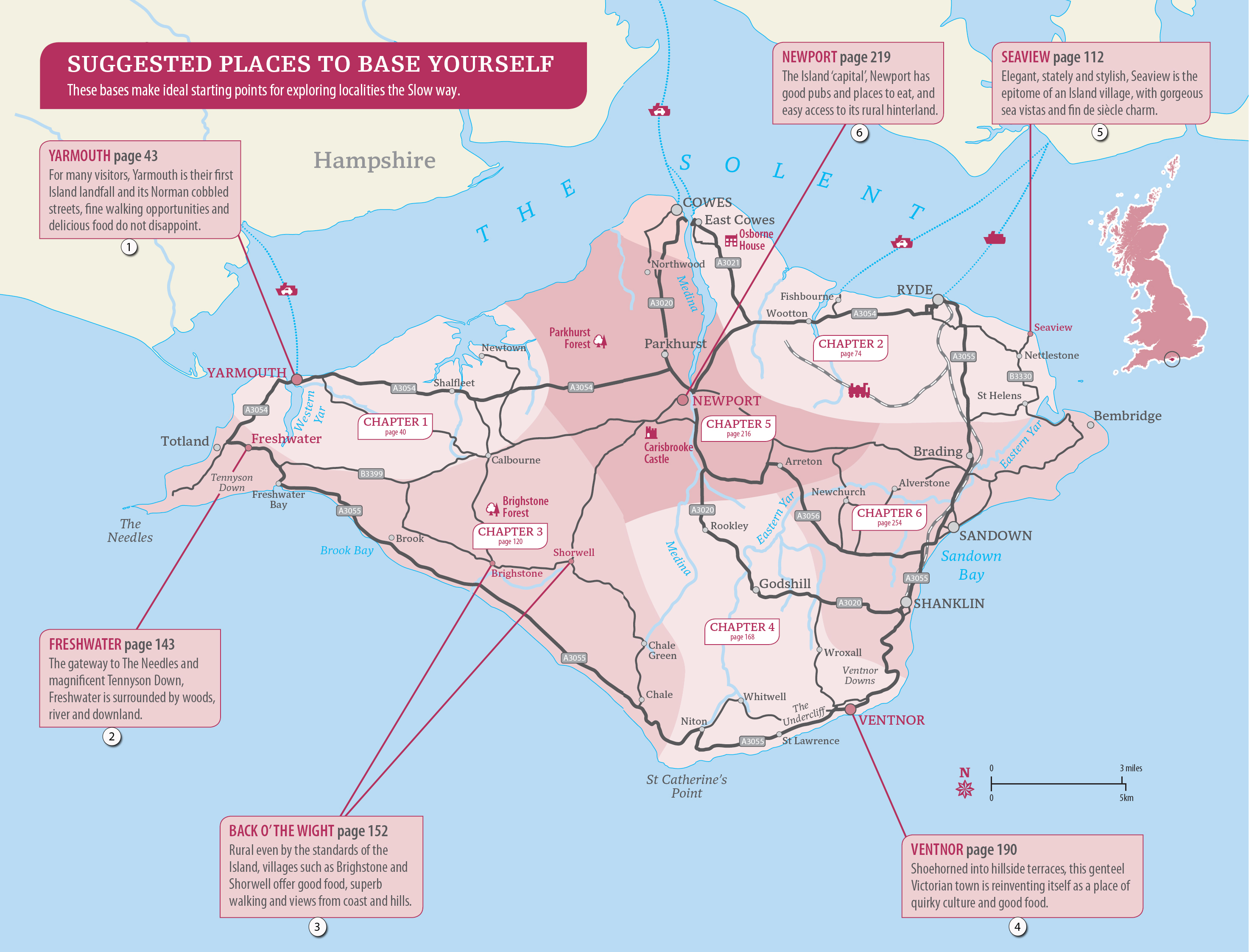

GOING SLOW ON

THE ISLE OF WIGHT

At the narrowest point of the Solent, between Hurst Castle in Hampshire and Fort Albert on the Islands northwest edge, the Isle of Wight floats barely a mile off the coast of the British mainland. Yet with no commercial airport or tunnel you must take to the sea to reach it: that requirement alone demands that, in a literal sense, you must slow down and begin to shed the hurried pace of everyday life before you have even arrived. Then, when on dry land, you will find little reason to quicken your pace.

The Island is large enough to lose yourself on, but small enough for this not to matter: just keep walking and that creek you amble along will eventually wind its way to a village pub or, failing that, another slice of a part of the world that is easy on the eye.

Guidebook authors are invariably asked to single out a favourite place, but on the Isle of Wight I find that impossible. Where would I possibly start? I could point to the haunting coastline around Newtown and Shalfleet where woodland edges dip their roots in the ebbing shallows and mudflats, or the Norman town of Yarmouth with its fine cafs and delis. The red squirrels pretty much anywhere you look, the extraordinary jumble of geology that makes up the Undercliff or dawn flooding the Solent, viewed from the shingle spit that keeps Seaview dry. Then theres the spectacle of a peregrine falcon darting along the guillotined edges of Tennyson Down, the mournful call of a nightjar in Brighstone Forest, or stumbling across dinosaur fossils. Each one has a strong claim on the heart strings of visitors.

The cheek by jowl nature of seaside paraphernalia and natural drama on the Island often borders on the surreal. Just a few minutes cycle from the archetypical resort of Sandown you can lean your bike against a hedge and watch an egret hunting for fish in a serene mire; you might catch a red squirrel out of the corner of your eye, furiously clambering upside down along an overhanging branch. Elsewhere, you might heave yourself up the vertiginous slopes of Ventnor Downs, taking in a sweeping coastline that pulls away to the middle distance. But while one moment you may get carried away with the being at one with nature ethos, the next you may encounter a Victorian seaside amusement park. Some visitors can find such a combination intrusive; others have certainly been known to sneer. To me and for most Islanders they seem to rub along perfectly well. Far from being mutually exclusive, they are all part of the Island DNA.

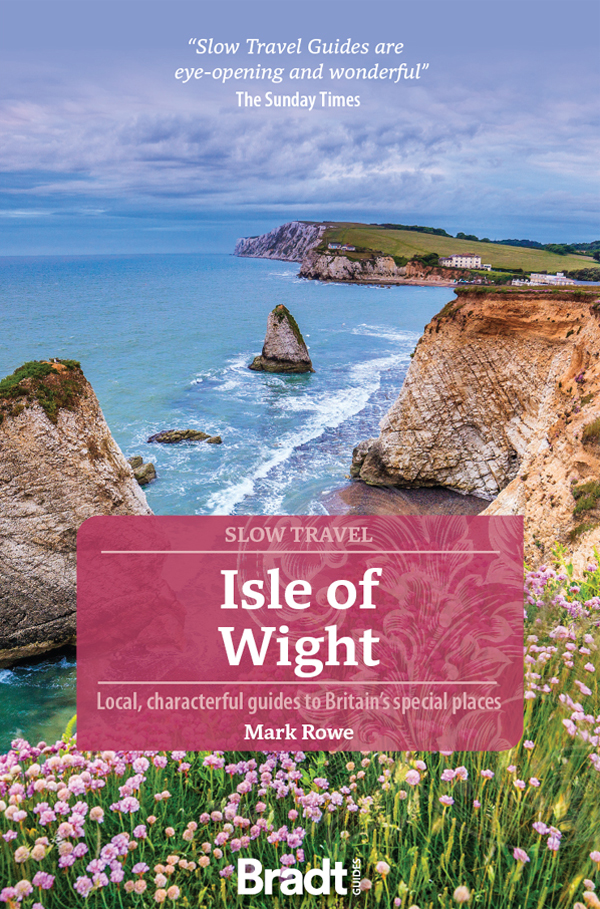

View from Niton towards St Catherines Point.

THE SLOW MINDSET

Hilary Bradt, Founder, Bradt Travel Guides

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

T S Eliot, Little Gidding, Four Quartets

This series evolved, slowly, from a Bradt editorial meeting when we started to explore ideas for guides to our favourite part of the world Great Britain. We wanted to get away from the usual top sights formula and encourage our authors to bring out the nuances and local differences that make up a sense of place such things as food, building styles, nature, geology or local people and what makes them tick. Our aim was to create a series that celebrates the present, focusing on sustainable tourism, rather than taking a nostalgic wallow in the past.

So without our realising it at the time, we had defined Slow Travel, or at least our concept of it. For the beauty of the Slow Movement is that there is no fixed definition; we adapt the philosophy to fit our individual needs and aspirations. Thus Carl Honor, author of In Praise of Slow, writes: The Slow Movement is a cultural revolution against the notion that faster is always better. Its not about doing everything at a snails pace, its about seeking to do everything at the right speed. Savouring the hours and minutes rather than just counting them. Doing everything as well as possible, instead of as fast as possible. Its about quality over quantity in everything from work to food to parenting. And travel.

So take time to explore. Dont rush it, get to know an area and the people who live there and youll be as delighted as the authors by what you find.

These two elements have co-existed for the best part of 180 years: sweet shops and bustle characterise Shanklin yet Darwin found the town, which sits in the shadow of magnificent Jurassic cliffs, sufficiently peaceful and scenic that he chose it as the place to write up his paper On the Origin of Species. Nor did poets, from Alfred, Lord Tennyson to Lewis Carroll and John Keats, find their reveries interrupted by the Islands appeal to the wider public.

I once chatted to Simon Davis, founder of Wight Salt (see box, ) on Ventnor Pier. As he patiently peeled off his wellies after a morning wading in the shallow seas harvesting saltwater, he laughed when I said my journey across the Island to Ventnor had taken much longer than Id expected. The Island forces you to go slowly, he said, there are no trunk roads where you can drive at 70mph and I think that has a trickle-down effect on Island culture. Simon was spot on: you dont have a choice, you have to slow down on this Island and that helps you get the most out of a visit.

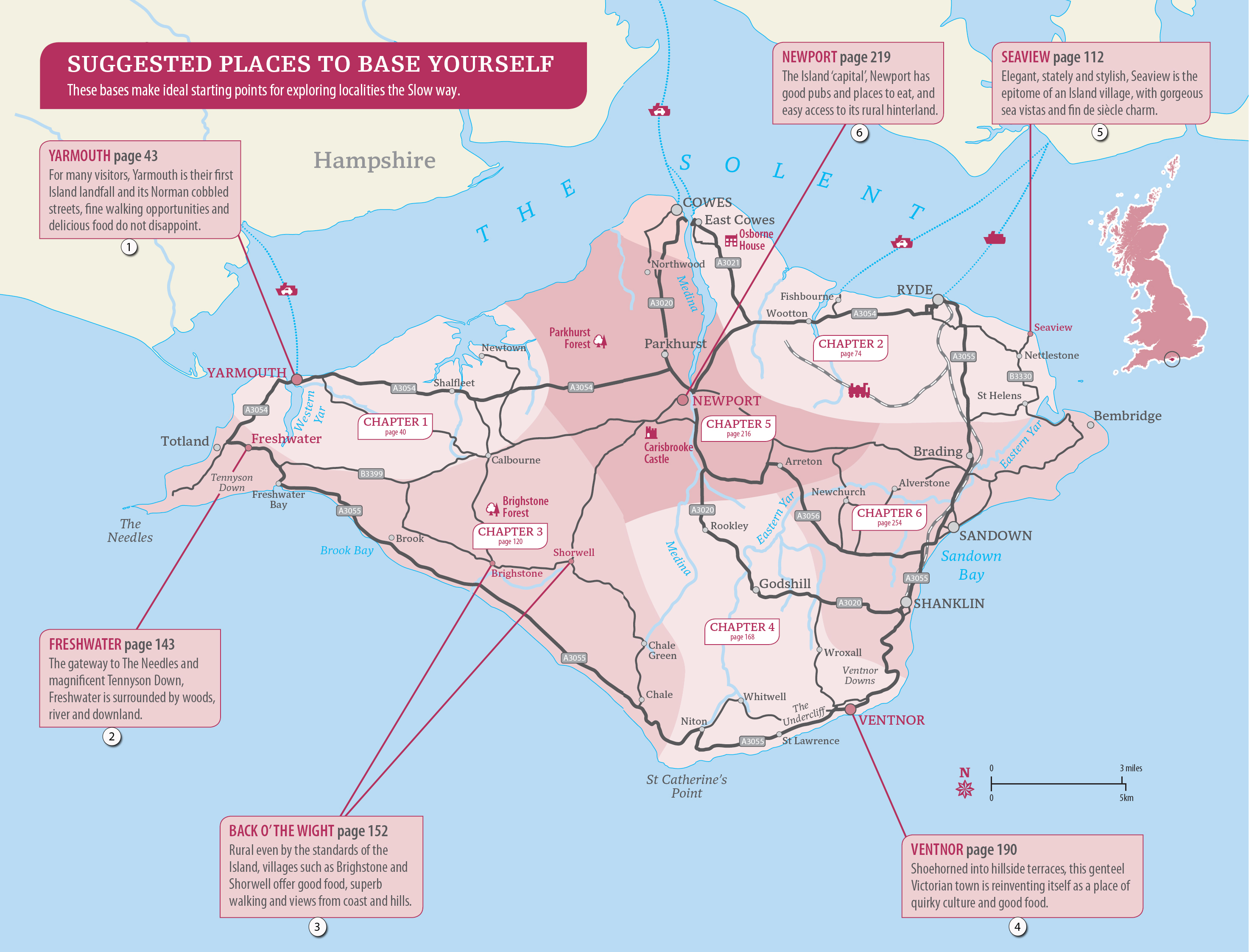

THE ISLAND

Take a map of the Isle of Wight, step back from it and you may at a push perceive the Island to resemble a large vertebra in shape. This would be apt, for 125 million years ago the Island once hovered where North Africa is today and the humid climate of the time led to it being an ideal habitat for several species of dinosaurs. A little more recently for the past 6,000 to 10,000 years or so the Solent has kept the Island separate and discrete from the mainland, not just physically but culturally and environmentally. Romans, royalty and the great and good of the literary world have all lain their helmets, crowns, wide-brimmed hats and quills here.

Island life has been sustained by sunny climes congenial to growing crops and grazing livestock. Everything has been to hand: building materials from the beach and quarries in the form of stone; reeds from the marshes; timber from the forests; lime from chalk pits; and abundant cowpats that could be used to make bricks or for waterproof insulation. The northerly forests were once full of wild boar and deer, while the Solents creeks still harbour fish, oysters and crabs along with plump (but now off limits) migrant geese. The coastal and southern chalk downlands are still generally given over to sheep, while the foothills of these downs feed streams that water lower-lying fields where beef and dairy herds graze.

The Island extends 13 miles northsouth and is around 26 miles broad in the beam, its west and east fringes joined by a chalk backbone that wobbles from one coast to the other. Along the way that chalk ridge buckles into superb rolling downlands, the folds of which were created 300 million years ago. On the north coast these undulations calm down and fragment into haunting wetlands and creeks. To the south they come to an abrupt full stop in the form of high cliffs.