Stopping Wars

Stopping Wars

Defining the Obstacles to Cease-fire

James D.D. Smith

First published 1995 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1995 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smith, James D.D.

Stopping wars : defining the obstacles to cease-fire / by James D.D. Smith.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8133-2467-X ISBN 0-8133-9980-7 (pbk)

1. Armistices. 2. War (International law)

JX5173.S65 1995

341.6dc20

94-47232

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-9980-5 (pbk)

For my family, and for Clare

For better or worse, this book began as a PhD dissertation, and although many changes have been made to the original work, those who supported and helped me through that time deserve as much gratitude now as then. Thanks first of all go to my supervisor Efraim Karsh, whose thorough scholarship and attention to detail ensured a greater understanding of the wars 1 have studied than might otherwise have been possible. Though we may have differed on any number of issues, these differences only served to strengthen the work in the end. Moreover, there was never any question about his willingness to help.

Some people have read the manuscript, or parts of it, and supplied helpful criticism at a number of crucial junctures. Of these, I am most grateful to Barrie Paskins at the University of London and Trudy Govier at the University of Calgary; both found the time to read various incomplete drafts despite the imposition on their time. I have also benefitted greatly from comments and support from Hugh Miall, Andrew Acland, Adam Curie, Sydney Bailey, Greta Brooks, and Jane Saunders. Finally, a great debt is owed to James Gow for his advice on many portions of the manuscript that deal with Yugoslavia. Needless to say, what follows is my responsibility alone and should not necessarily be taken to be representative of any of their opinions.

Finally, I would like to thank the Association of Commonwealth Universities, who funded a great part of the original research, and the British Council, who judiciously administered those funds.

Some of the material in appeared previously in the Journal for Peace Research and is reprinted here with their kind permission.

J.D.D.S.

Bradford, England

Part One

Introduction

1

The Long and Winding Road to Peace

The road from war to peace is a puzzling and uncertain one. To those who fight and die on it, it is seldom clear just when the journey will end; those responsible for finding the path are rarely more perceptive. Of the few signposts that exist, perhaps the most visible is the cease-fire: no war ends without one. To reach that point on the road, however, a number of obstacles must be overcome. Many of these will be conflict-specific; that is, they are more or less unique to the violent conflict in question, and are either unlikely to be encountered a second time, or are too specific to place into broad theoretical constructs. It seems likely that at least some of the difficulties encountered, however, will be common to virtually all cease-fire negotiations, whether between or among non-state or extra-state actors, nations and nation-states. These difficulties, strewn like rubble across the path to peace, come up time and time again, and if attempts at stopping wars are to be consistently successful, they need to be identified and addressed. This book, then, is an attempt to understand what stops wars from ending. More specifically, since there must be a cease-fire before any war can end, and since the cease-fire is the most obvious sign that the war may be ending, the book is an attempt to catalogue the most common barriers to successful cease-fires in international and civil wars.

At first glance, there is a single, uncomplicated explanation to this problem, one that many of us have been hearing all our lives. As a child, I can remember watching footage of the Second World War and other conflicts, and thinking, "Why can't they just stop fighting?" I could not accept the possibility that all those people really hated each other so much and that there was no more sensible way to resolve their differences. When I asked adults the answer to my question, they invariably replied, "Because they don't want to stop." (In academic terms, the political will was absent: the leadership, whoever they may have been, believed that more could be gained by fighting than by not fighting.) Today, the violence of the former Yugoslavia, of Somalia, and of Rwanda and elswhere, leads me to ask the same question I did when I was younger, and people still give me the same reply now as they did then. One of the points of writing this book is to propose that their answer, sincere and guileless though it may be, is simply not good enough.

Admittedly, the most obvious obstacle to stopping a war is in fact a lack of political will. Unless it is present, and excepting those cases where a cease-fire is imposed, no cease-fire will occur. Yet even where there is some will to cease fire, what researchers have failed to recognize is that a number of factors sometimes affect its translation into effective and sufficient political will which actually brings the fighting to an end. This study therefore qualifies and deepens the more traditional theories of war termination which suggest that where both sides want an end to their war, the war will end.

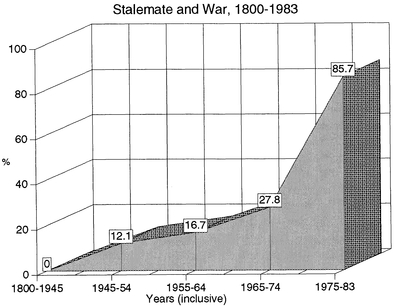

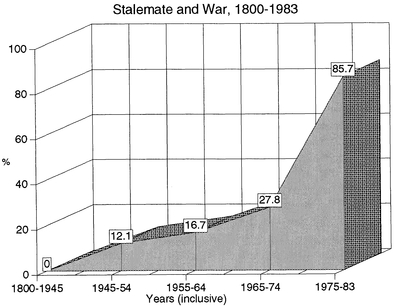

Stalemate and War, 1800-1983. Percentages refer to wars where military stalemate was considered to be the decisive factor in belligerents' decisions to try to end the war. Raw data can be found in Dunnigan and Martel, 1987, pp. 207-262. It is noteworthy that their own (valid) conclusion was that only 11% of wars since 1800 have ended in stalemate (p. 270).

for an illustration.) The existence of any obstacle decreases the likelihood of a cease-fire, and while their removal does not automatically end the fighting, it will make this more likely.

For anyone with a humanitarian interest in ending war, the importance of understanding the process of cease-fire should be obvious: if we can work out how to remove these barriers, actively encouraging possibilities for cease-fire, the chances of being able to stop the violence must increase dramatically. On the practical level, too, an understanding of the process is a sensible step. It is of course possible to argue that when there is a straightforward winner/loser relationship between belligerents stopping the fighting tends to be much more laborious and intricate. The power relationship between belligerents is more equal, but the belligerents themselves may not see it that way, and may make conflicting demands justified on the basis of how much power they think they have. It is thus that an understanding of the process of cease-fires is important in a practical sense, for whereas wars in the past have tended to end on clear victor-vanquished terms, this appears now to be much less often the case.