Copyright 1991 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cole, Sally Cooper, 1951

Women of the praia : work and lives in a Portuguese coastal community / Sally Cole.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-09464-0 -- ISBN 0-691-02862-1 (pbk.)

1. Women fishers--Portugal--Vila Ch (Porto)--Case studies. 2. Women fish trade workers--Portugal--Vila Ch (Porto)--Case studies. 3. Women--Portugal--Vila Ch (Porto)--Social conditions. 4. Women--Portugal--Vila Ch (Porto)--Economic conditions.

I. Title.

HD6073.F652P83 1991 91-2359

331.483920946915--dc20 CIP

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-02862-0

ISBN-10: 0-691-02862-1

eISBN: 978-0-691-21485-6

R0

PREFACE

IN THE SPRING of 1984 I went to Vila Ch, a village on the north coast of Portugal, to study women, work, and social change. I was interested in women in fishing economies, and there had been little written on the subject at that time. I was also interested in Portugal. I knew that, since the Revolution of April 25, 1974, Portuguese society had been undergoing rapid social, economic, and political changes but that, until the decade leading up to 1974, the country had, under the Salazarean New State, experienced the slowest rate of growth in Western Europe. And I knew that, despite rapid and radical change, it remains the most underdeveloped country in Western Europe. In a Portuguese rural community, I thought, changes in womens work might be documented through an analysis of the changes in the work of three generations of womenthe earliest being the generation born before the First World War and married before the Second World War, during the Salazarean regime. I chose to focus on the coastal zone north of Porto where fishing was an important part of the traditional economy, an area that has been among those of most intensive industrialization in the contemporary period.

As a graduate student at the time, I was also concerned with theoretical and methodological problems I had identified in two bodies of literature, the ethnography of Southern or Mediterranean Europe and the writing on women and economic development. I was concerned that despite the avowed interest in Mediterranean women and the assertion that Mediterranean societies are societies preoccupied with gender (Ortner and Whitehead 1981), we knew very little about the women. Through the anthropologists concept of honor and shame we knew that women were daughters of fathers, wives of men, and mothers of sons, but we knew little about womens work, their property relations, their relations with other women, their values and aspirations, or their own perceptions of themselves and of the role of women in society. We knew about women only in their relationships with men. Men were the subjects of Mediterranean ethnography; women were the other. And the result of this framework was that women were understood primarily as victims of their sexuality (Schneider 1971).

Although I recognized the validity of the then-current feminist socialist women-and-development theoretical framework, the resulting literature was also problematic for me, and for reasons similar to those that rendered the traditional ethnography problematic: the values, agendas, and strategies of the women themselves were not heard. In the ethnography, the analysis of external and global processes of change took precedence over the subjective experiences of individuals and groups. In this literature women were being portrayed as victims of development. The women-and-development framework apparently had not been applied to a Mediterranean caseand this was one of my tasksbut I was interested in integrating the voice and experience of actual women into a discussion of women and socioeconomic change in Portugal. It was for these reasons that I chose to record womens life stories.

Finally, I was interested in the relationship between womens work and the social construction of gender. I believed there was a strong relationship between the two: that the work which women do is related to the gender images that are operative in societies, and that as womens work changes, so do gender ideologies. But the burgeoning literature on the anthropology of women in the late 1970s and early 1980s treated these as two separate spheres of analysis. There were abundant studies of women and work where ideology was neglected (Beneria and Sen 1981; Etienne and Leacock 1980; Fernndez-Kelly 1983; Luxton 1980; Young, Wolkowitz, and McCullagh 1981; Zavella 1987), and there were abundant symbolic analyses of gender that ignored the analytical importance of material conditions and social change (Ardener 1975; McCormack and Strathern 1980; Ortner and Whitehead 1981). Rarely were the two integrated. The anthropology of women was mirroring the split between materialist and symbolic anthropologists but was not reflecting the actual experience of women for whom the symbolic and the material worlds are both real. Again, I hoped to present an integrated view that would more accurately represent the lived experience of real women rather than create an artificial separation between the different spheres of womens lives.

The extent to which I have realized my agenda is for the reader to judge. I certainly had the full cooperation and assistance of the women of Vila Ch, who know better than I how their lives are integrated. I am extremely thankful to them and to them I hope I have been true. My concern in this regard was significantly allayed by one of these very women: having sent a copy of the dissertation on which this study is based to Vila Ch, where it circulated among numerous households, I received a letter of reply. Lauras student daughter (Lauras story appears in the text) wrote to tell me that her mother recognized herself and was pleased. I would like to thank Laura and the women of Vila Ch for the warmth, openness, and hospitality they showed me during the time I was a resident of their community. Especially, I would like to thank Clara and her family, Alice and her family, Carmelina and her family, and Beatriz (now deceased), Gracinda, Constncia, Angelina, Teresa, Maria, Ins, Maria Ins, and Ana Maria.

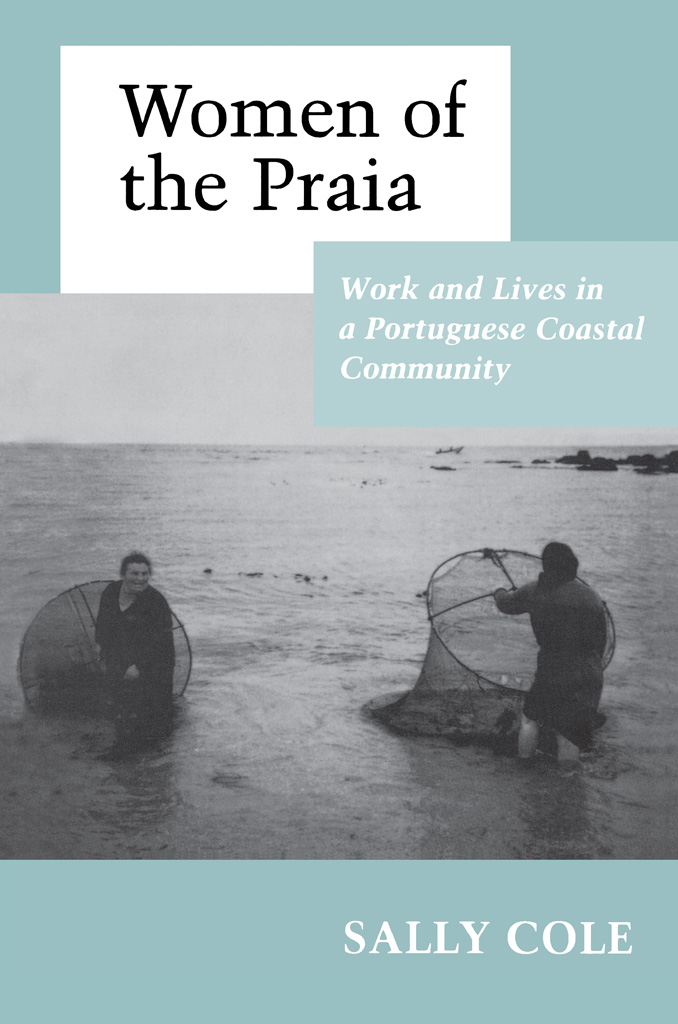

I lived in Vila Ch for thirteen months from May 1984 to June 1985 and returned during the summer of 1988. I went to Vila Ch after three months residence in Lisbon, where I had been studying the Portuguese language and exploring Portuguese secondary and primary source material. After the traffic, pollution, and crowded apartment living of the city, Vila Ch in the spring and summer offered a welcome opportunity for outdoor life and physical work. My first view of the community was on a rainy May morning when women were at work on the beach, wading waist-deep in the water, collecting seaweed in huge circular hand nets and spreading it to dry on the sand. The women welcomed an extra pair of hands, and I felt that the characteristics of this community, where women are engaged in such physical work and where they work in public view rather than isolated in their homes, would make easier the anthropologists initial task of finding a place in the community. When one of the women mentioned a small house that was usually rented to Portuguese vacationers during the summer but that could be rented to me for the entire year, Vila Ch seemed the obvious place to unpack my bags. This three-room housea renovated shed once used to store fishing gear and dried seaweedstood on the main street that runs across the head of the beach in the heart of the fishing community, and it became my home during my year in Vila Ch. My neighbors on both sides were the owners of small grocery shops that also served as taverns for the fishermen. The fishing boats and fish auction were only a few meters away.