CONTEMPORARY ASIAIN THE WORLD SERIES

CONTEMPORARY ASIA IN THE WORLD

David C. Kang and Victor D. Cha, Editors

This series aims to address a gap in the public-policy and scholarly discussion of Asia. It seeks to promote books and studies that are on the cutting edge of their respective disciplines or in the promotion of multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary research but that are also accessible to a wider readership. The editors seek to showcase the best scholarly and public-policy arguments on Asia from any field, including politics, history, economics, and cultural studies.

Beyond the Final Score: The Politics of Sport in Asia, Victor D. Cha, 2008

The Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online, Guobin Yang, 2009

China and India: Prospects for Peace, Jonathan Holslag, 2010

India, Pakistan, and the Bomb: Debating Nuclear Stability in South Asia, umit Ganguly and S. Paul Kapur, 2010

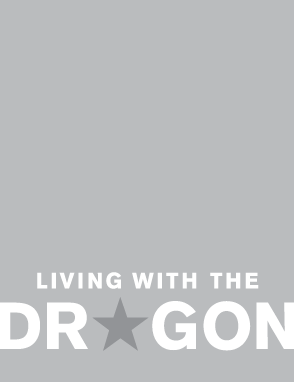

HOW THE AMERICAN PUBLIC VIEWS

THE RISE OF CHINA

BENJAMIN I. PAGE TAO XIE

Columbia University Press/New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2010 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52549-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Page, Benjamin I.

Living with the dragon : how the American public views the rise of China /

Benjamin I. Page and Tao Xie.

p. cm.(Contemporary Asia in the world)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-15208-2 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-231-52549-7 (e-book)

1. ChinaForeign public opinion, American. 2. United States RelationsChina. 3. ChinaRelationsUnited States. 4. Public opinionUnited States. I. Xie, Tao. II. Title. III. Series.

E183.8.C5P26 2010

327.51073dc22

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing.

Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Mary, Can, and Youwen

with love and appreciation

Andrew J. Nathan

American China specialists spend a lot of time worrying about how Chinese foreign policy is made. But the reverse question is in some ways more puzzling: how do we in America make our policy toward China? The most important part of the answer is the one most often overlooked: the guiding role of public opinion in a democracy. It now stands revealed by Benjamin Page and Tao Xie.

The United States and China are an odd couple when it comes to policymaking toward one another. In China, a small group of leaders deliberate among themselves to lay down the principles that guide policy. They suffer no interference from the national legislature or media. Their directives are implemented by a disciplined bureaucracy that nearly always sticks to message. Official media trumpet the guiding principles in unison. The Chinese people take the policy as given. Few are known to dissent from it.

In the United States, it is hard to know who is in charge. Presidents come and go every four or eight years. Instead of representing a single ruling party with a consistent policy, presidents come from competing parties that claim to have different stands on all kinds of issues. Each new president, even if he comes from the same party as his predecessor, wants to do something new. Moreover, presidents do not control the legislature or the bureaucracy, and have to negotiate with them or work behind their backs to get anything done. Under our separation of powers, courts can weigh in with decisions of their own. And in our federal system, states and even cities can announce their own trade sanctions or hold ceremonies for victims of repressionor do the opposite, and grant concessions to attract investment. All this takes place amid an intense scrum of disputation among lobbies, media, think tanks, Congressional caucuses, and talking heads. Policymaking is hidden behind the dust of struggle and seems endlessly unstable.

Is China a threat or not? Should we seek smooth relations with the people in power even though they rule undemocratically, or should we punish them for human rights violations like those in Tibet and Xinjiang? Should we deepen trade relations which allow China to grow richer and more powerful, or interrupt them to punish China for currency manipulation and intellectual property rights violations? Is Chinese military modernization a threat to U.S. interests or do we need China as a partner to keep the peace in Asia? Do we blame China for supporting the dictators in North Korea, the Sudan, and Myanmar, or thank China for creating a channel of influence over them? Is China helping to modernize Africa or seeking to displace Western interests there, and in Latin America and the Middle East? Do we want China to rise, or dont we?

As Americans noisily debate these questions, Beijings America specialists struggle to explain to their leaders where our China policy is headed and why. Does U.S. pressure to open Chinese markets reveal a plan to take the lions share of profits from the economic relationship and use it to sustain American hegemony? Are the U.S. relationships with Japan, India, and Vietnam aimed at tying China down with a ring of potential threats? Why does the U.S. deter Chinese military pressure on Taiwanis this part of a strategy to weaken China by keeping it divided? Oras other Chinese analysts claimis U.S. policy essentially strategy-free, the jerrybuilt result of compromises and tradeoffs among competing interest groups, bureaucracies, members of Congress, religious movements, human rights organizations, and business lobbies? As China grows in global importance, there are few groups or institutions without a stake either in cozying up to China, or in punishing it.

China policy accordingly has seen continuous debates and disruptionsover Taiwan, trade disputes, human rights, and military accidents. The United States placed sanctions on China after the 1989 Tiananmen tragedy, and some of those sanctions quietly survive today (for example on the sale of higher-end military technology to China). Many Americans called for a boycott of the 2008 Beijing Olympics to protest Chinas failure to do more to stop the genocide in Darfur. Many deplore Chinas repressive policies in Tibet. Democrats have come to office promising to protect American workers from unfair Chinese competition; Republicans have come to office promising to demonstrate overwhelming military strength to deter any Chinese challenge; and leaders of both parties have promised to do more to protect democracy in Taiwan and fight for religious and political freedom in China.

Yet, paradoxically, behind the noise, American China policy since Richard Nixon has followed a consistent line. In 1967 Nixon wrote, We simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors. Our aim, to the extent that we can influence events, should be to induce change. Nixons policy was labeled engagement, and it has survived under one name or another under every president since. Washington normalized diplomatic relations with Beijing, ushered China into the World Trade Organization, and built up the most intensely interdependent trade and investment relationship in the world. Engagement took as its premise the fact that China was there and would not go away. It accepted that the rest of the world would have to live with China, and that we could only influence, not control, its direction and pace of change. Most boldly, engagement made the radical commitment that a prosperous and strong Chinafor all challenges it might bringwould be more consistent with American interests than a poor and turbulent China.