ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank those who aided me in preparing this book while I labored on other chores, such as editing a venerable monthly magazine on American culture and opinion and collaborating with a cohost on a weekly podcast program. Working on this book became something that I was forced to pursue among other tasks. Fortunately, I was able to inflict my proliferating chapters on certain patient readers, particularly Joseph Cotto, who is my podcast collaborator; Robert Paquette of the Alexander Hamilton Institute; Alex Riley, professor of Social Thought at Bucknell University, and Ed Welsch, executive editor of Chronicles. Without their timely comments, I would still be organizing my thoughts for a book that would still be in outline form. I am also grateful to Stanley G. Payne, who is the dean of American and possibly world fascist scholars. Professor Payne praised my book on fascism most of all because of its discussions of antifascism. This convinced me that if I went back to my earlier research, I would focus on the antifascists from the 1920s to the present.

Acknowledgment is also due to my two perceptive readers, Professors Grant Havers and Paul Robinson, who, after reading my manuscript, exchanged notes with me about how to improve my text. I benefited enormously from both these exchanges. I should also acknowledge the assistance provided by Chronicles publisher, Devin Foley, who persuaded me to present my views on antifascism on several of his Backchannel podcasts. These talks and the chance to answers questions about my research helped clarify for me, perhaps even more than for listeners, topics I was then addressing. I should also mention in gratitude my wife Mary and computer expert Pamela Evans, both of whom repeatedly rescued me from my technical klutziness in retrieving lost texts.

Most of all I am grateful to Cornell University Press editor and longtime friend Amy Farranto, who helped me shake off my senescent lethargy to finish this work. Each time I sent some material to Amy with a hopeful message appended that this was the end, she came back with a note to write more. She also went over my completed chapters and removed superfluous passages (often drenched with sarcasm). Without Amys editorial advice and steady words of encouragement, this project would not have come as far as it has.

INTRODUCTION

The following study of antifascism as a pervasive ideological force may be read as a sequel to my 2016 book Fascism: Career of a Concept.

Among our elites there is a growing unwillingness to treat fascism as a movement that belonged to a specific time and place. The term fascism functions as a resource that the speaker, whether a journalist, actor, comedian, educator, politician, or member of the clergy, can lay hold of to demonize an opponent. In the interwar period antifascist critics were usually coherent and criticized a movement that had taken power in a Western country. But critical discussions of fascism, particularly since World War II, have become both diffuse and imprecatory. Today the f-word is wielded mostly to bully and isolate political opponents or impose on the unwilling an unrequested therapeutic reconstruction.

Most alarmingly for many observers, antifascist activism has led to violence, a trend that escalated in the United States with the election of Donald Trump but has been going on for decades. From 1968 onward the Rote Armee Fraktion in Germany went on a rampage against supposed Nazis in the German government and business community. Before it came to an effective end in 1978, this German antifascist underground managed to murder thirty people while unleashing other forms of physical destruction. At the same time antifascist terrorism was launched by Red Brigades in Italy, which resulted in, among other casualties, the death of Premier Aldo Moro in 1978. In England since 1985 acts of terror against an alleged fascist threat have been perpetrated by, among others, Anti-Fascist Action (AFA). More recently, since the election of Donald Trump in 2016, Antifa activists have swung into action in large cities across the United States. In this country, however, such turbulent activism on the Left is nothing new. In the 1960s antiwar protests often turned violent, and in the late 1980s, Anti-Racist Action (ARA) was organized by leftist punk fans to fight the Right. According to Peter Beinart, this last group took its name because Americans were more familiar with fighting racism than they were with combating fascism. This conflation of fascism and racism (along with other isms) is something I address in this book.

After observing the eruptions of violence from bands of militants who claim to be protecting society against a violent Right that is often nowhere to be seen, I was motivated to examine the political culture fueling this trend. The crusade of violent antifascism is often no more than the final stage of a process of indoctrination that political, educational, and cultural elites have engaged in since the middle of the twentieth century. What this crusade represents is an intensification or exaggeration of an official teaching, the spillover effect of a militancy that already permeates vital political and social institutions.

The antifascist crusade is promoted through the deliberately indiscriminate use of the term fascism, a tendency that George Orwell warned against in his Tribune article of 1944. Although Orwell could not possibly be identified as a fascist and, in fact, fought in the Spanish Civil War on the side of the Republican Left, he balked at the misuse of the word:

By Fascism they mean, roughly speaking, something cruel, unscrupulous, arrogant, obscurantist, anti-liberal and anti-working-class. Except for the relatively small number of Fascist sympathizers, almost any English person would accept bully as a synonym for Fascist. But Fascism is also a political and economic system. Why, then, cannot we have a clear and generally accepted definition of it?

Orwell concluded that it is because it is impossible to define Fascism satisfactorily without making admissions which neither the Fascists themselves, nor the Conservatives, nor Socialists of any colour, are willing to make. All one can do for the moment is to use the word with a certain amount of circumspection and not, as is usually done, degrade it to the level of a swearword.

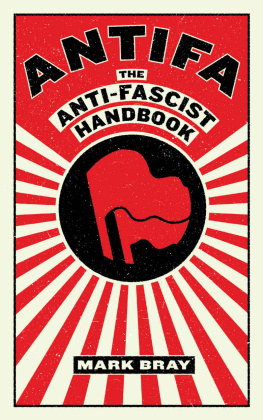

It is certainly understandable that during a struggle against Nazi Germany, which was then allied to fascist Italy and a military dictatorship in Japan, fascism in England would have a blurred definition. More puzzling is the abuse of the word in the twenty-first century. Mark Bray, a chief theorist of Antifa, has repeatedly decried a ubiquitous fascist danger.

Illustrating the antifascist mood of our time is a broadside by Jacob Siegel of Tablet magazine (2016) targeting my scholarship. Siegel scolds me for suggesting that fascism is peculiar to interwar Europe and that generic fascism was less destructive in its effects than Nazism. Both these suppositions were once widely accepted and may still be by some members of the academic fraternity. One encounters my interpretation in the work of Stanley Payne, who was long the dean of fascism studies in the United States. Like other distinguished historians, Payne defines what he considers generic fascism in interwar Europe and distinguishes it from Nazism, without denying there were overlaps between the two movements. Unlike Nolte, I stress the nihilistic, violent character of Hitlers national revolution, which distinguishes it from the run-of-the-mill revolutionary Right. It is difficult for me to see how the Nazi orgy of killing was simply a variation on Latin fascism or similar in character to something as anodyne as Austrian clerical fascism.