Templeton Press

300 Conshohocken State Road, Suite 500

West Conshohocken, PA 19428

www.templetonpress.org

2014 by John J. DiIulio Jr.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Templeton Press.

Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

DiIulio, John J., Jr., 1958-

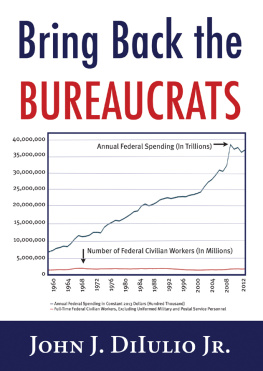

Bring back the bureaucrats : why more federal workers will lead to better (and smaller!) government / John J. DiIulio Jr.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59947-467-0 (alk. paper)

1. Administrative agenciesUnited StatesManagement.

2. BureaucracyUnited States. 3. Civil serviceUnited States.

4. Public administration--United States. 5. Government productivityUnited States. I. Title.

JK421.D55 2014

331.76135173--dc23

2014027492

Printed in the United States of America

14 15 16 17 18 19 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Donald F. Kettl

Americas foremost public administration scholar

A great teacher, a loyal friend, and a dear man

Acknowledgments

I HAVE LEARNED ABOUT American government and public administration (or bureaucracy) from many great scholars, but I am especially lucky to have learned from these eight: Jack H. Nagel, Henry Teune, Jameson W. Doig, Gerald J. Gerry Garvey, Richard P. Dick Nathan, Mark H. Moore, James Q. Wilson, and Donald F. Kettl.

Nearly forty years ago, I took my first bureaucracy course with Jack at the University of Pennsylvania. I was hooked. Jack was my main undergraduate mentor, and he became my Penn colleague, dean, and comrade in sustaining the Master of Public Administration (MPA) program at Penns Fels Institute of Government. Jack is a gentle genius, and his wise counsel, both personal and professional, are among my lifes treasures. I also took several undergraduate classes with Henry, plus a de facto graduate seminar on research methods that he offered to me during weekly one-on-one office hours that ran several hours each week. I was reunited with Henry when I left Princeton for Penn, and we coadvised several students on public administrationtype theses or dissertations; by rights I should have paid Henry tuition, because he never stopped teaching me.

I cotaught the core MPA public management course at Princetons Woodrow Wilson School with Jameson, an unfailingly kind and generous colleague whose disagreements with my views on crime and corrections resulted only in wonderful discussions and whose seminal work on public leadership and innovation repays reading to this day. As with Jameson, I cotaught and also did training for federal workers with Gerry, who helped to inform the very best of the thinking and writing about public administration that I did while at Princeton, including my essay on the federal governments principled agents.

I also cotaught Princetons core public management MPA course with Dick and later collaborated with him on Brookings books on health care administration and also a field network study involving government partnerships with religious nonprofit organizations. Our collaboration continues. Even as he nears his eightieth birthday, I have to race just to keep up with him as we proceed with our ongoing national study of the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, better known as the ACA or Obamacare. And the only person to rival Dick for the title of the most inspiring and public-spirited academic I know is Mark. I never took a course with Mark, and we never served on the same faculty together (not counting my stint a few years ago as a visiting professor at the Harvard Kennedy School). He pioneered and led the executive sessions that helped to revolutionize thinking about policing in America. That is just one such remarkable, real-world accomplishment among many that are all to his great and lasting credit. His mentorship and scholarship have enlivened and leavened my thinking for more than three decades now, and his writing about creating public value is and shall remain the gold standard for creative and public-spirited public management scholarship.

Jim Wilson was my mentor for thirty-two years, including two decades during which I had the honor to be the coauthor of his magnificent American government textbook. He often beckoned me to revise his 1989 magnum opus Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies Do and Why They Do It and to publish it as my own. I never took him up on that absurdly generous offer, but, in the year before he died, I did promise him that I would publish an article summarizing my thinking on big intergovernment and its private administrative proxies. I did, and he lived long enough to read and comment on it. I also promised him that I would get around to researching and writing a weighty scholarly tome on the subject that might make him proud.

In 2012, shortly after Jim died, my friend (and fellow Philly-bred boy) Peter Dougherty, editor-in-chief at Princeton University Press, signed me up to do that book. It is tentatively entitled The Daddy State: Facing Up to Big Government; it should be in Petes hands (and will be dedicated to Jim) in 2015. Templeton Presss Susan Arellano worked with Pete at Free Press back in the days when it was led by the great Erwin Glikes. Erwin, for whom I did my first book, Governing Prisons: A Comparative Study of Correctional Management, in 1987, used to talk about a book becoming the text of the debate on a given issue. From my work on religion and faith-based initiatives, I have known many folks at the John Templeton Foundation for years. But I did not know Susan. In 2013, she had a bug about me doing a book on bureaucracy planted in her ear by Yuval Levin, editor of National Affairs and the most insightful young conservative thinker in America today (thanks, Yuval). She reached out to me. She suggested, and Pete agreed, that the debate on big government was big enough for two texts on the topic. They jointly conceived the present book as a crystallization of certain core concerns and prescriptions, and the next book as an attempt to refine, extend, and deepen the analysis and prescriptions in relation to the literature on American political development that, as I conceive it, begins not with late twentieth-century political science but with the nineteenth-century observer of American democracy (and its penitentiaries!), Alexis de Tocqueville.

So, I am very grateful to Pete, and I am thankful and indebted to Susan for hatching the idea of doing this book and for all her editorial TLC. Her firm but gentle hand kept me from writing a much (much) longer book (Petes!), and she persuaded me to take her counsel on the present books prescriptive title: bring back the bureaucrats indeed! I am also indebted to Susans Templeton Press colleague, Trish Vergilio, for shepherding me through an expedited editing and production process with southern charm and northern efficiency; thanks, Trish.