Representations of Classical Greece in Theme Parks

Imagines Classical Receptions in the Visual and Performing Arts

Series Editors: Filippo Carl-Uhink and Martin Lindner

Other titles in this series

Art Nouveau and the Classical Tradition, by Richard Warren

Classical Antiquity in Heavy Metal Music, edited by K. F. B. Fletcher and Osman Umurhan

Classical Antiquity in Video Games, edited by Christian Rollinger

A Homeric Catalogue of Shapes, by Charlayn von Solms

Orientalism and the Reception of Powerful Women from the Ancient World, edited by Filippo Carl-Uhink and Anja Wieber

The Ancient Mediterranean Sea in Modern Visual and Performing Arts, edited by Rosario Rovira Guardiola

Contents

Templo de Kinetos, Terra Mtica, Benidorm, Spain: The Temple of Zeus at Olympia

The entrance to the dark ride Happy World, Happy Valley Beijing, Peoples Republic of China

Pontius Pilates praetorium in Tierra Santa, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Statue of Poseidon, Europa-Park, Rust, Germany

The loading station of the water coaster Poseidon, Europa-Park, Rust, Germany

The madhouse Cassandra, Europa-Park, Rust, Germany

Die Fahrt des Odysseus, Belantis, Leipzig, Germany: The Trojan Horse

Die Fahrt des Odysseus, Belantis, Leipzig, Germany: Charybdis

Detail of the restaurant Acropolis, Terra Mtica, Benidorm, Spain: The Porch of the Caryatids

Los caros, Terra Mtica, Benidorm, Spain

Auditorio de Pandora, Terra Mtica, Benidorm, Spain

Poseidons Fury. Escape from the Lost City, Universal Studios, Orlando, USA

The Trojan Horse in Mt. Olympus, Wisconsin Dells, USA

The Entrance to Mt. Olympus, Wisconsin Dells, USA

The roller coaster Hades 360, Wisconsin Dells, USA

The themed area Aegean Harbour in Happy Valley Beijing, Peoples Republic of China

Happy Valley Beijing: Greek warriors

Statue next to Trojan Horse, Happy Valley Beijing

Trojan Horse, Happy Valley Beijing

Trojan Horse on the Trojan Plaza, E-Da Theme Park, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

The Cyclops from Big Air, E-Da Theme Park, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

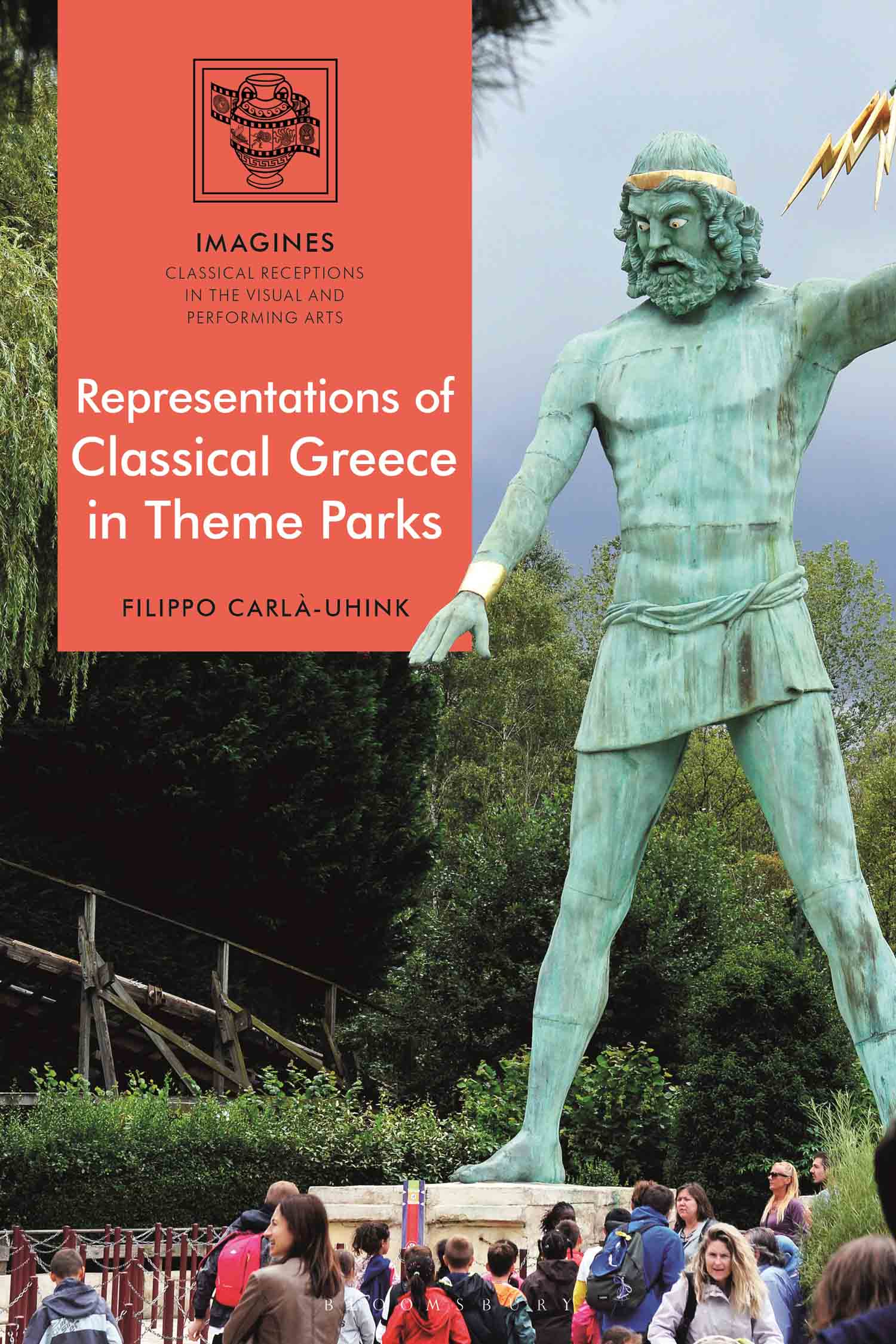

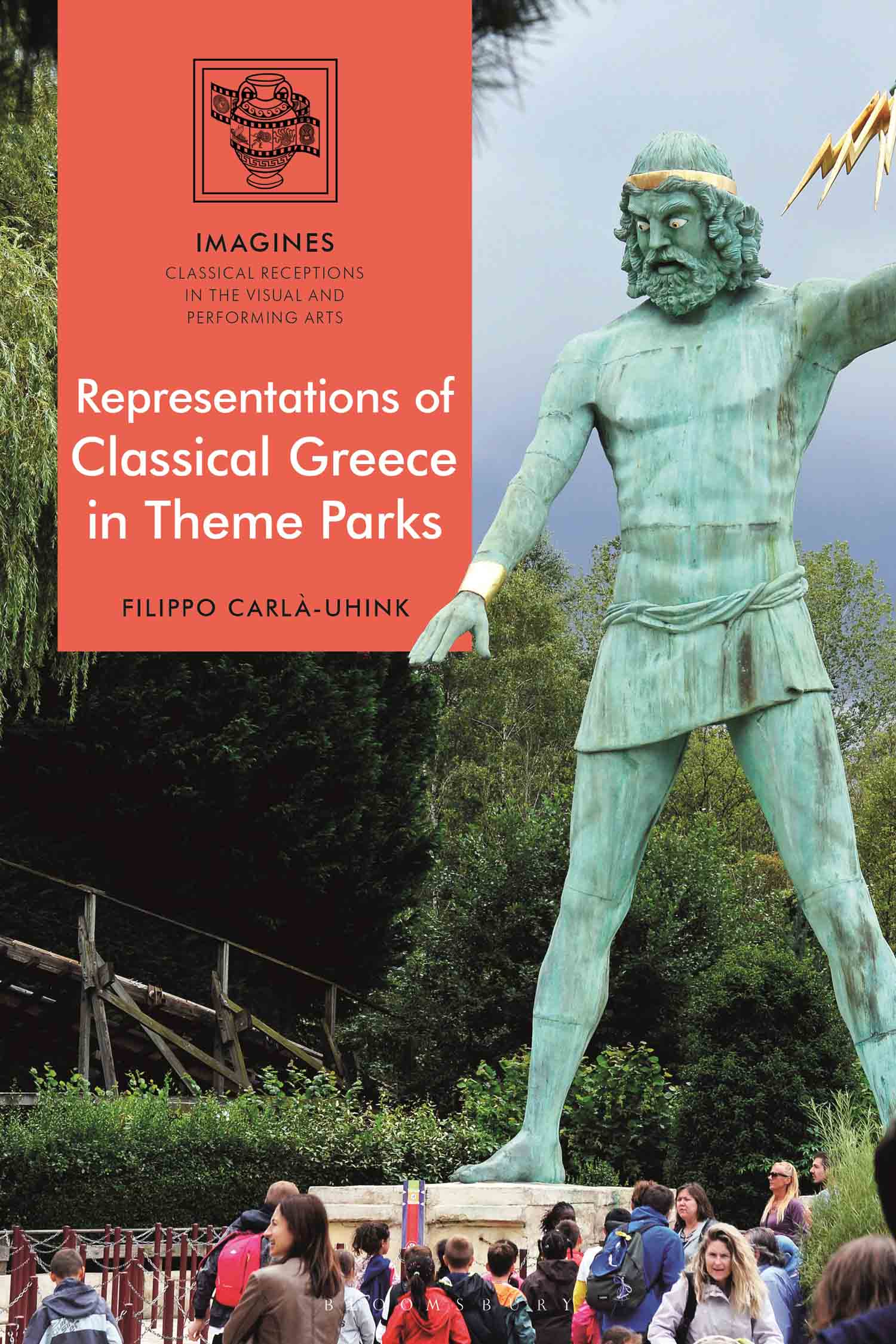

The Vase of Heracles, Parc Astrix, Plailly, France

Discoblix, Parc Astrix, Plailly, France

Loading station of Tonnerre de Zeus, Parc Astrix, Plailly, France

The project of this book began through a chance encounter and some shared interests with Florian Freitag, with whom I began to discuss theme parks and how we might be able to make them the object of our research in 2012. The first common trip to Terra Mtica was the outcome of those discussions, after which we not only started publishing together, but were also able to secure a generous research grant from the German Research Foundation (DFG) for a project on Time and Temporality in Theme Parks, which we directed together from 2014 to 2017. Sabrina Mittermeier and Ariane Schwarz cooperated on the project and thus participated in the research trips organized in that context. To them, and to all the people I visited theme parks with, goes my gratitude. Special thanks go to Nicolas Zorzin, who was essentially the victim of a trap I set: as he lives in Taipei, and is an archaeologist researching in the field of cultural heritage and uses of the past, I invited him to join me for a couple of days in Kaohsiung. Little did he know what was expected of him. I am very glad that we are still friends, and that he has found interesting material for his own research; surely, I profited immensely from his knowledge during our visit to E-Da World.

It is rather obvious that a research project such as that which Florian and I led cannot imply visiting only the seven parks investigated here, nor meeting only the people I spent time in these parks with: many other parks needed to be seen, and I met leading researchers in theme park studies, together developing crucial discussions on theory and methodology at conferences, at dinner, or in the parks themselves. I am particularly grateful to Scott A. Lukas, who came to Mainz in 2013 as a guest professor on invitation from Florian and me, and with whom we visited, among others, the Disneyland Resort and Universal Studios in Los Angeles. His knowledge of the theme park world and his insights are unique, and without him this book would not only look very different; it would not exist. Gordon Grice was also with us in Anaheim, and on other occasions. His perspective as an architect and designer of theme parks was at times invaluable in moving me on from strange theoretical reflections, bringing my attention back to practical issues. In Germany, I found a colleague and a friend in Jan-Erik Steinkrger: no one knows the park of Phantasialand as well as he does, and his impulses, once again deriving from another discipline (geography), have set my chain of thought into motion many times. Cline Molter has opened my mind to the ethnological approach to theme parks, and to a world I had never really considered before: that of religious theme parks. In this same field, I was able to have a dialogue with Crispin Paine, who also allowed me to read his monograph before it was published. I also would like to thank people I did not meet in person, but who answered my questions via email, providing me with information, pictures and videos that I could use for my study. All of them work for companies that construct theme park attractions, and they have been crucial sources of information for many points dealt with in this volume. I thank them in alphabetical order: George Dobler (Sunkid), Menno Draaisma (Mondial Rides), Charlotte van Etten (Vekoma), Kathrin Siegert (Huss) and Peter Ziegler (BeAR). Last but not least, the anonymous reviewers at Bloomsbury contributed with their precious advice to make this book more reader-friendly.

If there is one thing I learned while working on this book, and more generally while working on theme parks, it is how challenging and difficult, yet at the same time wonderfully exciting, interdisciplinarity is. I had the great fortune of being able to interact with excellent scholars from a hugely broad spectrum of other disciplines, but always in a very relaxed climate based on mutual respect, a desire to learn from each other, as well as on humour and good spirits. Research on theme parks continuously built and reinforced a strong friendship with Florian, and no visit to a theme park even when beset by weather, nuisances, technical problems or whatever came to pass ever finished without having laughed most of the time. For this reason, this book is dedicated to him.

In Anaheim, the original ride caters to the worldview of the public that was expected when the ride was developed mostly US Americans. while the geographical positioning reveals an Orientalizing gaze which locates Greece among the post-Ottoman countries, thus attributing it to Asia.

Moving on to Orlando, Greece is still located in Asia, but it is the first country the riders meet in this section, in direct contiguity to Europe. The scene is much bigger, and while the main element remains the same Pan flute-playing shepherd with lambs, he is located in a broader landscape of ruins. The idea of Greece as pristine and uncontaminated landscape has disappeared in favour of a more symbolic representation, dominated by the colours of the Greek flag: the white of the ancient buildings and the blue of the hills, mountains, and even of the sunflowers. The columns are more stylized and abstract but still recognizable as Ionic; the number of columns and pediments is greater, and in the background a mountain with a temple on the top is likely a visual reference to the Parthenon, here meant to signify Mount Olympus. Classical culture is thus highlighted over natural Greece, even if the latter does not disappear (life in Greece after the classical period is still represented as playing music to lambs), and Greece in general seems to attract more attention.

Next page