Landmines are weapons of mass destruction in slow motion. They are inhumane, indiscriminate and cause unnecessary suffering, even decades after the forces that laid them stopped fighting. The landmine embodies a view of the world in which a human life can be snuffed out by an automated device. The person who placed and armed the mine may be on the other side of the world even dead when it finally explodes under the foot of a farmer planting rice, a child on the way to class, a refugee returning to their destroyed home. By the late 1980s, thousands of people in countries such as Afghanistan, Angola, Bosnia, Cambodia and Mozambique were being maimed and killed by landmines, while governments continued to act like they were normal weapons. Millions of mines moved around the world in arms transfers that faced little scrutiny.

In the face of this dehumanized killing, though, humanity pushed back. Survivors, deminers, humanitarian workers, grassroots activists, human rights advocates and journalists raised the alarm. They demanded the worlds militaries live up to their own principles in the laws of war. They called on the countries that had made a killing in the arms trade to help clear the deadly fruit of their irresponsible profiteering. Out of this groundswell emerged the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), which I helped launch as its first coordinator in 1991. By 1997, the ICBL had persuaded the majority of the worlds countries to adopt a treaty comprehensively banning anti-personnel mines and establishing obligations to clear contaminated land, assist victims and provide risk reduction education to affected communities. That year, the ICBL and I were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for starting a process which in the space of a few years changed a ban on anti-personnel mines from a vision to a feasible reality.

The Nobel Committee recognized the ICBL for the unprecedented way its global network of organizations had made it possible to express and mediate a broad wave of popular commitment, enabling governments of several small and medium-sized countries to take up the issue and deal with it. Indeed, the landmine ban treaty has been monumental success. Even countries that have so far refused to sign it such as the United States, Russia and China largely follow its prohibitions. The mass manufacture and trade in landmines have ground to a halt. Thousands of acres of contaminated land have been cleared; victims have received prosthetics, medical and socio-economic support.

The Nobel Committee was also prescient, seeing in the ICBL a model for similar processes in the future, saying that it could prove of decisive importance to the international effort for disarmament and peace. Just over a decade later, a similar campaign the Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC) succeeded in pushing governments to negotiate a ban on cluster munitions. These insidious weapons spray explosive bomblets over a wide area; many fail to explode upon impact and become de facto anti-personnel landmines. And in 2017, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for persuading 122 countries to adopt a treaty banning the worlds most destructive and inhumane weapons. ICBL, CMC and ICAN standard bearers of what is known as the humanitarian disarmament movement have shown that ordinary people, organizing across national boundaries and forefronting the voices of those most affected, can resist the seemingly inexorable march of violent technology.

Having seen the power of humanity over automated and indiscriminate killing, I am confident that civil society has the capacity to face the emerging threat of what diplomats have euphemistically called lethal autonomous weapons systems. Weapons developers are seeking to pervert the power of information and communications technology for deadly ends, taking humans entirely out of the decision to kill. In the autonomous, weaponized robot, they are essentially designing mines that actively seek out their targets, that can follow you, that can fly. This is why I support the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, which is using the humanitarian disarmament model to ban all weapons that fail to maintain meaningful human control over violence.

But even as we resist new threats of digitized slaughter and celebrate the successes of the humanitarian disarmament community, we cannot forget that landmines have not yet been eradicated. In fact, due to the horrifying carnage in Afghanistan, Myanmar, Syria and Yemen, the long-term decline in new landmine casualties has, since 2015, begun to reverse. Many governments have flagged in their commitment to clear all the worlds minefields by 2025. And landmine survivors continue to struggle against the pervasive discrimination and stigma directed at people with disabilities. As this book went to press, the Trump Administration reversed longstanding US policy on landmines. Like many of his decisions, it is a step backward into a more cruel past. We must redouble our efforts to destroy all stockpiles of landmines and cluster munitions, demine all contaminated land, ensure every victims human rights and universalize the landmine and cluster munition ban treaties.

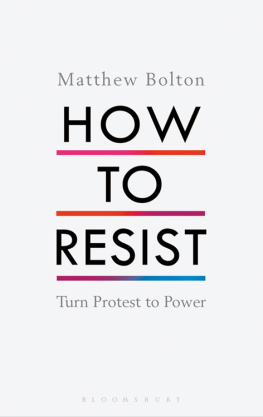

In this book, Matthew Breay Bolton documents the story of these inter-locking struggles for humanity in this world riven by automated violence. In doing so, he draws on his extensive experience working in humanitarian fieldwork, diplomatic settings and academia. He approaches efforts to eradicate landmines and tackle other problematic weapons through the inclusive lens of human security as opposed to more narrowly focused national security concerns. Bolton examines the depersonalization of killing that has accompanied the use of unmanned aerial vehicles or drones and flags the need to tackle the multiple challenges posed by fully autonomous armed robots. Throughout, Bolton emphasizes the role of civil society to show how when ordinary people work together they can achieve extraordinary impact. He invites you to join the global struggle for peace and justice, refusing to leave decisions of life and death to a machine.

Jody Williams Chair, Nobel Womens Initiative 1997 Nobel Peace Prize Co-Laureate with the International Campaign to Ban Landmines Author of My Name Is Jody Williams: A Vermont Girls Winning Path to the Nobel Peace Prize.

Matthew Bolton documents his experience working in humanitarian fieldwork, diplomatic settings, and academia. He approaches efforts to eradicate landmines and tackle other problematic weapons through the inclusive lens of human security as opposed to more narrowly focused national security concerns. Bolton examines the depersonalization of killing that has accompanied the use of unmanned aerial vehicles or drones and flags the need to tackle the multiple challenges posed by fully autonomous armed robots. Throughout Bolton emphasizes the role of civil society to show how when ordinary people work together they can achieve extraordinary impact.

Jody Williams, 1997 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and Chair of the Nobel Womens Initiative, former coordinator of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, author of My Name Is Jody Williams: A Vermont Girls Winning Path to the Nobel Peace Prize .

Matthew Bolton takes us on a very readable journey to what in Bosnia we used to call the Dark Side. He starts as an idealistic young aid worker and becomes almost by accident an expert on landmines and the politics of landmine clearance, which is minefield in itself. His account of unsettling experiences in Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan and South Sudan is a vivid snapshot of the dangerous times in which we live.